1) Inter-American Development Bank JAMAICA – Logistics Chains Study Final Report March 2013 in association with CA#7011

2) Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Study Overview ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 2.2 Performance of the Trucking Industry ......................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Ports ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.4 Freight Railways ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2.5 Trade Facilitation ......................................................................................................................................... . 5 2.6 3 Country’s Road Infrastructure ...................................................................................................................... 4 Logistics Management of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) ...................................................... 6 Macro Level Analysis of Logistics Performance ..................................................................................................... 7 3.1 3.2 Global Competiveness Index, World Economic Forum ................................................................................ 9 3.3 Doing Business 2013 †The World Bank Group and the International Finance Corporation ...................... 1 1 3.4 4 Global Enabling Trade Report, World Economic Forum .............................................................................. 7 Logistics Performance Index, World Bank .................................................................................................. 2 1 Jamaican Logistics Industry at the Macro Level .................................................................................................. 9 . 1 4.1 4.2 Road Freight Transportation ...................................................................................................................... 2 2 4.3 5 Road Network ............................................................................................................................................ 9 1 Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Supply Chain Management and Logistics ....... 5 2 Micro Sector Analysis of Logistics Performance .................................................................................................. 7 2 5.1 Agriculture Sector ...................................................................................................................................... 8 2 5.2 Mining Industry Sector ............................................................................................................................... 0 3 5.3 Manufacturing Sector ................................................................................................................................ 3 3 5.4 Tourism Sector ........................................................................................................................................... 4 3 5.5 Retail and Wholesale Sector ...................................................................................................................... 5 3 Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates

3) 6 Micro Level Analysis – Interviews ........................................................................................................................ 6 3 6.1 6.2 Port Costs ................................................................................................................................................... 1 4 6.3 Limited Ocean Carrier Service .................................................................................................................... 1 4 6.4 Small Number of Importers and Small Volumes ........................................................................................ 2 4 6.5 Customs Clearance ..................................................................................................................................... 2 4 6.6 Small Lot Sizes for Internal Delivery ........................................................................................................... 3 4 6.7 Internal Road Network ............................................................................................................................... 4 4 6.8 7 Dependence on Imports ............................................................................................................................ 8 . 3 Bureaucratic Issues in Obtaining Export License ........................................................................................ 5 4 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................... 6 4 7.1 Improve Highway Infrastructure ................................................................................................................ 7 4 7.2 Increase Warehouse Capacity .................................................................................................................... 7 4 7.3 Development of Buyers Groups ................................................................................................................. 8 4 7.4 Reduce Port Costs ...................................................................................................................................... 8 4 7.5 Reduce Customs Clearance Time ............................................................................................................... 9 4 7.6 Development of a Container Transshipment Hub and Logistic Center ...................................................... 0 5 7.7 Development of a Concession to Operate a Container Transshipment Hub in Kingston .......................... 4 5 7.7.1 Conduct a Feasibility Study to be used in Marketing Potential Investors ............................................. 4 5 7.7.2 Estimate Enterprise Value of Potential Concession ............................................................................... 5 5 7.7.3 Prepare Letter of Interest ...................................................................................................................... 6 5 7.7.4 Develop a “Short List” to Receive Request for Proposal ....................................................................... 6 5 8 Conclusions .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 5 9 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 5 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix A †Interview Questionnaire Appendix B †List of Institutions, Agencies and Companies contacted for Interviews and Existing Data Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates

4) 1 Introduction The Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) retained the services of EAC Consulting, Inc., in association with Martin Associates to conduct a Logistics Chains Study for the island of Jamaica. The purpose of the Logistics Chains Study is to identify the major links in Jamaica’s logistics supply chains that includes sources of inputs of labor, capital, and raw materials to production sites; and from the production sites to storage facilities, major logistics hubs, local markets and international gateways. The study targets the major types of freight logistics services including cargo transportation by land and sea, warehousing, consolidation, customs clearing and forwarding, container operations, and multiâ€modal transportation. Other areas of interest include cargo handling at ports as well as valueâ€added services, such as the provision of warehousing and supply chain management solutions. Due to the budgetary limitations of the current study, an inâ€depth analysis of each of these linkages in the supply chain could not be explored. Therefore, the study is focused on identifying the key constraints in the supply chains of the major industries within Jamaica, and the impact of freight logistics on the competitiveness of Jamaica’s industry and economic sectors, both domestically and internationally. A set of recommendations has been developed to improve the domestic logistics system within Jamaica, as well as to improve the international competitive position of Jamaica in terms of international transshipment and logistics. The results from the study have been arranged in such a way as to facilitate their consideration by governments and private investors for implementation with possible support from the IDB. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 1

5) 2 Study Overview An assessment of the internal logistics systems within a country involves the analysis of the inbound logistics of raw materials moving to the production process sites and the outbound logistics of moving products from the production process sites to markets. This includes domestic products as well as imported and exported products. The critical elements of a logistics supply chain include the following elements: ï‚· Infrastructure: – Highways – Airports – Ports – Rail – Warehousing/Distribution Centers ï‚· Regulatory: – Customs – Immigration – Tariffs – Security ï‚· Information flow: – Tracking of goods and inputs – Integrated systems of transportation service providers with shippers/consignees – Inventory control policies The study consists of two (2) phases. The first phase of the study is a macro overview of the current logistics industry in Jamaica and how Jamaica compares with other Caribbean countries with respect to the efficiency of the logistics supply system, both internally and externally. The second phase of the study is a micro analysis that is based on interviews with logistics managers of leading industries in Jamaica. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 2

6) The macro analysis is based on a review of the literature focusing on logistics systems in emerging markets, and identifies Jamaica’s relative position with respect to the logistics supply systems present in other similar markets. In addition, the literature review provides a summary of the key factors within the logistics systems of emerging countries and identifies potential solutions to specific areas of concern within the logistics supply chain. These macro findings are then cross referenced with the results of the interviews with the logistics managers of Jamaica’s leading industries (micro analysis) that represent the Country’s major economic sectors. In assessing the comparative logistics systems at the country level, the major obstacle is the absence of consistent and quantifiable data. As described in the Interâ€American Development Bank’s publication, Freight Logistics in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Agenda to Improve Performance1, “the performance of logistics in a given territory (a country for example), is not easy to measure or interpret.” The IDB report identifies three methods used to assess the logistics performance of a country. These are as follows: – A Macro approach based on national accounts that focuses on the relationship of transportation costs as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product; – A Micro approach which is based on interviews with key companies operating within a country; and – A Perception approach, which is based on performance indicators, developed from a large survey of transportation industry stakeholders. However, because of the complexity of the logistics systems and the uniqueness of these systems between countries and industries, it is difficult to develop such indicators for use in detailed analyses. The lack of transportation cost data and inventory data at the macro country level in most emerging markets, such as Jamaica and the Caribbean region in general, further complicates the development of logistics indicators, and exacerbates the task of identifying 1 Freight Logistics in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Agenda to Improve Performance, Jose A. Barbero, Inter†American Development Bank, Infrastructure and Environment Department, Technical Notes N0.IDBâ€TNâ€103, 2010 Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 3

7) intraâ€country logistics performance metrics as well as comparisons between countries. The most reliable and comprehensive logistics indicator is the Logistics Performance Index (LPI), which is documented in a publication by the World Bank in 2007, 2010 and 20122. This index is based on a survey of more than 1,000 transportation service providers in over 150 countries, and will be used in this macro assessment to provide interâ€country comparisons between the logistics supply chain in Jamaica and other Caribbean and Latin American countries. A review of the factors underlying the performance of a country’s logistics infrastructure indicates six major areas that are most critical in affecting the logistics supply chain.3 These factors are as follows: – Country’s Road Infrastructure – Performance of the Trucking Industry – Ports – Freight Railways – Trade Facilitation – Logistics Management of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) 2.1 Country’s Road Infrastructure Overall, the existing conditions of the roadway system in most Caribbean and Latin American countries reflect structural issues, including road degradation, a high ratio of unpaved to paved roadways, and mountainous terrain. An investment in road networks has been found to have a direct influence on freight logistics costs and enhances the mobility of a country’s population. 2 Connecting to Compete 2012, Trade Logistics in the Global Economy, The Logistics Performance Index and its Indicators, Jeanâ€Francois Arvis, Monica Alina, Mustra, Lauri Ojala, Ben Shepherd, Daniel Saslavsky, 2012, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. 3 Freight Logistics in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Agenda to Improve Performance, Jose A. Barbero, Inter†American Development Bank, Infrastructure and Environment Department, Technical Notes N0.IDBâ€TNâ€103, 2010 Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 4

8) 2.2 Performance of the Trucking Industry Within the Caribbean and Latin American economies, the trucking system dominates internal trade flows. However, limited macro data is available on the status of the region’s trucking industry. The ability to utilize fullâ€truck load shipments is important in minimizing trucking costs, but due to the dominance of small scale manufacturers and farming, less than a truck load (LTL) shipments are prominent in the Caribbean and Latin American markets. Consolidation of shipments to reduce the number of LTL shipments should be a goal for improving intraâ€country logistics and reducing trucking costs. 2.3 Ports The port system is the most critical node in the Caribbean region, due to the importance of international trade. It is noted that the development of public private partnerships in the port sector of the Caribbean and Latin American countries has resulted in acceptable port infrastructure, however overall port management models and associated regulatory structures are areas in need of improvement. The impact of investment in port infrastructure and management is critical to a country’s competitive position. 2.4 Freight Railways Railway usage is typically limited in Caribbean countries, and is frequently dedicated to bulk logistics movements as it plays an important role in connecting the ports to bulk operations. Private investment is characteristic of railway infrastructure investments. In addition to moving freight, railway usage also reduces emissions compared to trucking operations, and further reduces road damage and maintenance costs, as bulk materials are moved more efficiently by rail. 2.5 Trade Facilitation The factors that drive trade facilitation include regulatory policies, administrative structure, and documentation procedures. It is this area that research has indicated the lowest levels of development in the Caribbean and Latin American region. Next to port efficiencies, Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 5

9) previous studies by the IDB indicate that the factors that most influence a country’s competitiveness are customs efficiency and eâ€commerce. A focus on improving customs procedures and the time to clear customs are of paramount importance within the region. 2.6 Logistics Management of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) The Caribbean and Latin American region is characterized by a high concentration of employment within SMEs, but the importance of SMEs on international trade and competitiveness is limited. Analysis and research on the logistics structure of SMEs is very limited, however the data indicates that their logistics costs are two to three times larger than those of larger companies. Lack of monitoring of logistics costs within SMEs presents a measurement limitation, both in terms of transportation costs and inventory costs. Finally, the IDB report on Freight Logistics in Latin America and the Caribbean, states that “the Caribbean Islands are a special case”. Because of their small size, internal logistics is hardly relevant, and the administration of ports and airports as well as maritime and aero†commercial accessibility is of more importance. Studies on logistics performance seem to exclude smaller countries, thus making existing literature ineffective to identify needs4. 4 Freight Logistics in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Agenda to Improve Performance, Jose A. Barbero, Inter†American Development Bank, Infrastructure and Environment Department, Technical Notes N0.IDBâ€TNâ€103, 2010 Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 6

10) 3 Macro Level Analysis of Logistics Performance As noted in the overview, macro countryâ€wide transportation industry statistics are essentially nonâ€existent for most Caribbean Island countries, including Jamaica. As part of the literature review, the project team conducted numerous interviews with members of the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN), as well as reviewed data maintained by CARICOM and the Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ), in an attempt to identify macro logistics industry indicators such as transportation costs as a percent of value of goods sold, import share of value of goods sold, inventory carrying costs, and average inventory turn times. The lack of such published industry data complicates the ability of the project team to provide macro comparative analyses, and results in the need to review current and historical logistics performance indices prepared by the World Bank. These logistics performance indices are the recognized metric used by economic and research institutions to understand the logistics deficiencies within these countries, and compare on a standard basis the logistics performance between countries of similar size and geographic location. A review of these indices was undertaken and relevant aspects are summarized below. It is to be emphasized that all of these indices are macro in general, and can only be used for general information and for contextual purposes. 3.1 Global Enabling Trade Report, World Economic Forum The Enabling Trade Index ranks countries based on their level of necessary elements in place for enabling trade and whether there are improvements needed. The Index is divided into subâ€indices which include: Market Access, Border Administration, Transport & Communication Infrastructure, and Business Environment. Each category is broken down into pillars, which are also ranked. These combine to form an overall subâ€index ranking for each country. Jamaica ranked 79th out of 132 countries in the Enabling Trade Index. Other Caribbean countries ranked in the index comparison include Costa Rica at 43rd, Honduras at 78th, Nicaragua at 82nd, the Dominican Republic at 87th, Colombia at 89th, and Haiti at 128th. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 7

11) The first subâ€index is associated with Market Access, which analyzes how welcoming countries are with regards to imports and examines the level of foreign market access available for the countries’ exporters. The quality of the trade system and the level of protection that both importers and exporters have are also included in the analysis. Jamaica ranked 58th in this category, better than its overall ranking of 79th. The second subâ€index is associated with Border Administration. This index looks at how efficiently imports and exports occur within a country. This is further broken down into the following categories: Efficiency of Customs Administration, Efficiency of Importâ€Export procedures, and Transparency of Border Administration. Efficiency of Customs Administration looks at the services that are provided by customs authorities and other related agencies. Jamaica ranked 54th in this category. The Efficiency of Importâ€Export Procedures section evaluates the effectiveness and efficiency of clearance processes by customs and border control. This includes factors such as the number of days and documents required to import/export goods as well as the total cost associated with these activities, excluding tariffs. Jamaica ranked 84th, which is a relatively low ranking. Transparency of Border Administration looks at the prevalence of using undocumented extra payments or bribes that are connected with imports and exports as well as the perceived corruption of the country. Jamaica ranked 79th in this category. The third subâ€index is associated with Transport and Communications Infrastructure and determines whether a country has the necessary transportation and communication infrastructure in place to help facilitate the efficient movement of goods within the country as well as outside of its borders. Availability and quality of transportation infrastructure, availability and quality of transportation services, and availability and use of ICTs (Information and Communication Technology) are examined to create a weighted rank of 61st for Jamaica. Availability and quality of transportation infrastructure looks at factors such as percent of paved roads, the density of airports, and the level of transshipment connections available from the countries. It also takes into account the quality of the various types of transportation Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 8

12) infrastructure that are in place. With these subâ€categories, Jamaica ranked 45th, a relatively high ranking. For availability and quality of transport services, Jamaica ranked 74th. The number and quality of services available for shipments, such as liner services, the ability to track and trace international shipments, the timeliness of shipments in reaching their destination, general postal efficiencies, and overall competence of the local logistics industry are all taken into consideration in this ranking process. Jamaica ranked 78th in the availability and use of ICTs. ICTs are becoming increasingly more important for managing shipments and play a big role in facilitating customs clearance and communication. The fourth subâ€index is associated with the Business Environment, and examines the quality of governance and the regulatory and security environment by looking at the regulatory environment and the physical security subsectors. Overall Jamaica is ranked at 105th, a very poor ranking. The regulatory environment evaluates how conducive the country’s regulatory government is to trade by assessing the quality and openness to foreign labor in the country as well as policies and trade agreements. Jamaica ranked 69th for this subsector. However, Jamaica ranked 118th for physical security, which assesses each country’s level of crime and violence and how well the police force can enforce laws since this is can affect the delivery of goods. This index suggests the weakest performance by Jamaica is in the governance of the regulatory process, including a very poor performance in physical security. In addition, Jamaica has a very poor rating with respect to days and number of documents required in the export and import documentation process. 3.2 Global Competiveness Index, World Economic Forum The ability for a country to be competitive is important for its sustainability and prosperity. The Global Competiveness Index was developed by the World Economic Forum as a way to assess the competitiveness of countries throughout the world and provide guidance for improvements. The index looks at several categories, which are combined to determine each Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 9

13) country’s competitive state. These components fall under three categories: Basic Requirements for competiveness, Efficiency Enhancers, and Innovation and Sophistication Factors. With all components combined, Jamaica ranked 97th out of the 144 countries included in the Index, placing Jamaica in the bottom oneâ€third. Other Caribbean countries included in the Index are Puerto Rico which ranked 31st, Panama ranked 40th, Barbados ranked 44th, Costa Rica ranked 57th, Colombia ranked 69th, Trinidad and Tobago ranked 84th, Honduras ranked 90th, Dominican Republic ranked 105th, Guyana ranked 109th, Venezuela ranked 126th, and Haiti ranked 142nd. This does not place Jamaica in a desirable competitive position. To further examine this position, it is necessary to determine what problems Jamaica faces in increasing its competitive state. The first component category is Basic Requirements which includes the number of institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, and health and primary education of each country. Overall, Jamaica ranked 114th in this category, suggesting an overall poor macroeconomic environment. This category examines the stability of a county’s economy, which is impacted by high debt and high inflation rates. These factors make it less attractive for investors to invest in businesses in these countries. The other issue Jamaica faces is that it is ranked at 104th for Health and Primary Education. This subâ€index examines the health level of workers as well as the quantity and quality of basic education. Lower education levels can result in less sophisticated and lack of value added products being manufactured in Jamaica, ultimately decreasing its competiveness. The second component category is Efficiency Enhancers. These include levels of higher education facilities and training, goods market efficiency, labor market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, and market size. These sectors are each factors of efficiency in a country. When a country can perform at a higher efficiency level, it allows that county to be more competitive with other countries. With these components combined, Jamaica ranked 80th. The component with which Jamaica struggles the most, is Market Size, in which it ranked 100th. Since Jamaica has limited physical size, it is difficult to use economies of Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 10

14) scale to the advantage of the country. Because of this, Jamaica lacks a competitive advantage that larger countries face, therefore decreasing its competiveness. Country’s trade barriers also contribute to efficiencies in the supply chain. When trade barriers are lowered, trade usually increases, resulting in profitability for the country. Key in this is the dependency on imports of an island country such as Jamaica, and the need to improve that country’s position in the international market place, including the facilitation of an efficient import/export climate. The Global Competitive Index classifies the countries into difference stages of competitive development. These include: Factor Driven, Efficiency Driven, and Innovation Driven stages. Jamaica is in the efficiency driven stage. Countries in this stage must develop more efficient production processes and increase product quality in order to combat rising wages to become more competitive, and ultimately increase profitability. To increase efficiency, it is necessary to strengthen higher education and training, leading to more efficient manufacturing processes and value added services. Many other Caribbean and Latin American countries are in this stage, such as Costa Rica, Guatemala, Dominican Republic, Colombia, and Panama. 3.3 Doing Business 2013 †The World Bank Group and the International Finance Corporation The World Bank Group and the International Finance Corporation has recently released Doing Business 2013, which analyzes the ease of doing business in 185 countries. Jamaica’s ranking of 85th in 2012 is projected to decrease to 90th in 2013, which suggests that it is becoming increasingly more difficult to conduct business in Jamaica. Several factors are examined for each country to form a weighted rank. These factors include the processes of starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts, and resolving insolvency. The most problematic issues for doing business in Jamaica are obtaining reliable electricity services, paying taxes, and enforcing contracts. It will become more difficult to get electricity for businesses, increasing Jamaica’s rank to 123rd in 2013 from 110th in 2012. It took an average of 97 days in 2012 to get electricity for a business, while it is Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 11

15) projected to take 104 days in 2013. Latin America and the other Caribbean countries take 66 days on average. This makes it difficult for Jamaica to compete with other surrounding countries. Jamaica is projected to rank 163rd in 2013 for its tax paying process since there are more payments required of businesses than in other Caribbean countries. However, Jamaica has decreased this ranking in this area from 174th in 2012. Enforcing contracts is difficult in Jamaica as well. While it requires less days on average to complete a dispute compared to other Caribbean and Latin American countries, it costs 15% of the claim on average more than other countries. An advantage Jamaica has over the other Caribbean and Latin American countries is that it takes on average of seven days to start a business in Jamaica compared to an average of 53 in other countries. 3.4 Logistics Performance Index, World Bank “The Logistics Performance Index” (LPI), the most relevant of the indices reviewed with respect to the actual logistics performance in Jamaica at the macro level, provides a simple, global benchmark to measure logistics performance, filling data gaps in data sets by providing systematic, cross country comparisons. Resulting from a joint venture between the World Bank, logistics service providers, and academics, the LPI is built around a number of logistics professionals. By asking freight forwarders to rate countries on key logistics issues such as customs clearance efficiency, infrastructure quality, and the ability to track cargo, it captures a broad set of elements that affect perceptions of the trade logistics in practice.”5 The LPI consists of measuring the country’s performance in six areas: ï‚· Efficiency of Customs and Border Management ï‚· Quality of Trade and Transport Infrastructure ï‚· Ease of Arranging Competitive Priced Shipments 5 Connecting to Compete 2012, Trade Logistics in the Global Economy. The Logistics Performance Index and its Indicators, Jeanâ€Francois Arvis, Monica Alina, Mustra, Lauri Ojala, Ben Shepherd, Daniel Saslavsky, 2012, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 12

16) ï‚· Competence and Quality of Logistics Services ï‚· Ability to Track and Trace Consignments ï‚· Frequency of Shipments Reaching Consignees within Scheduled or Expected Delivery Times The LPI has been published for 150 †155 countries in 2007, 2010 and 2012. In 2012, Jamaica received an LPI of 124 out of 155 countries in terms of logistics performance, with a score of 1 being the best performer and 155 being the lowest. With respect to the LPI for Caribbean and Central American countries, only Haiti and Cuba had lower scores. Cuba received a score of 144, while Haiti’s score was 153 out of the 155 countries. In contrast, Mexico received a score of 47, followed by Panama with a score of 61. The Bahamas, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic all received scores of 80, 82, and 85 respectively. More importantly, Jamaica’s LPI has actually worsened over the 2007â€2012 period, falling from an LPI of 108 in 2007, to 118 in 2010, and 124 in 2012. Conversely, the LPI score for Mexico improved over the same period, increasing from a 56 in 2007 to 50 in 2010 and 47 in 2012. However, the LPI for other Caribbean countries displayed a similar decline to Jamaica. Panama fell from an LPI score of 51 in 2010 to 61 in 2012. Similarly, the LPI for the Bahamas fell from 78 in 2010, to 80 in 2012. The LPI for Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic also fell from 56 to 82 and 65 to 85 over the 2010 †2012 period respectively. The LPI in Cuba however increased from 150th to 144th, between 2010 and 2012. This comparison of changes in the LPIs indicate that in relative terms, the logistics systems in Jamaica, as well as in the majority of the other Caribbean countries, has not kept pace with the logistics developments in other parts of the world. It is important to note that while the logistics performance in Jamaica has not kept pace with that of other countries, productivity, as measured in terms of value added (in constant dollars) to employment in Jamaica has also fallen between 2002 and 2010 in nearly all economic sectors. Exhibit 1 compares value added per employee in 2002 and 2010 for the Jamaican economy. Value added Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 13

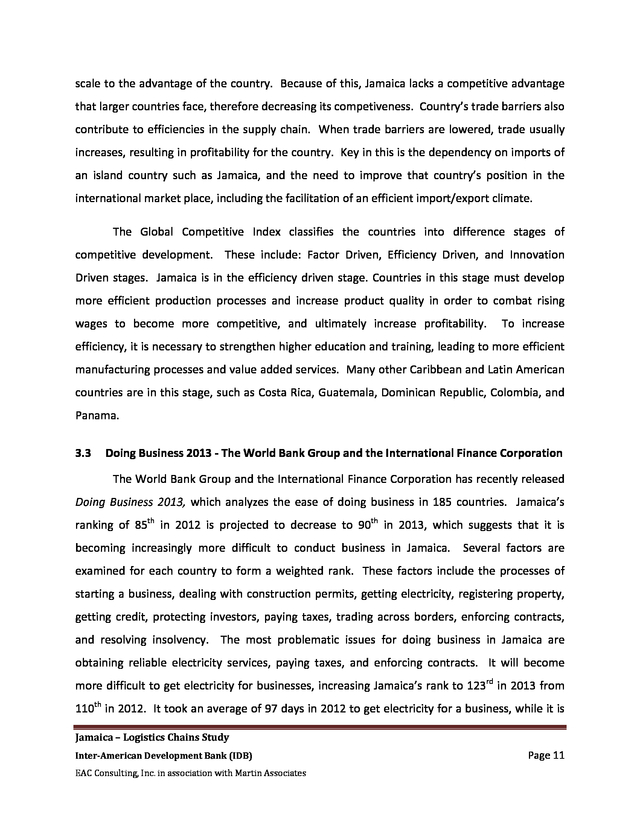

17) per employee shows a 10% decline in productivity in the Transportation, Storage and Communication sectors, which are the sectors most reflective of logistics performance. Overall, productivity fell in Jamaica by approximately 9% over the period. The largest losses in productivity were recorded for mining and quarrying, manufacturing, and wholesale and retail trade. Exhibit I: Comparison of Productivity (Value Added per Employee) (Constant J$, base 2007) $1,000/job $1,000/Job Percent Change Economic Sector 2002 2010 2010/2002 Agriculture, Forestry & Fishing $224 $197 â€12.24% Mining & Quarrying $7,556 $4,079 â€46.01% Manufacture $1,048 $839 â€19.91% Electricity & Water Supply $3,466 $3,660 5.59% Construction $589 $607 3.06% Wholesale & Retail Trade; Repairs; Installation of Machinery $767 $601 â€21.68% Transport, Storage & Communication $1,215 $1,095 â€9.88% Finance, Insurance, Real Estate, Renting, etc. $2,422 $2,078 â€14.20% Total $727 Source: Statistical Institute of Jamaica $663 â€8.77% The remaining portion of this section identifies the factors that the LPI has shown as inhibiting logistics performance in Jamaica. These factors are then used to compare with the findings of the detailed company interviews conducted by the project team regarding logistics performance within Jamaica. The logistics performance in Jamaica ranks in the lower quintile of all countries included in the LPI analyses. As previously noted, only Cuba and Haiti have a lower rated logistics system in the Caribbean and Latin American countries. In reviewing the factors most important in the logistics performance of a country, the World Bank identified that “trade related infrastructure, particularly roads, constrains the logistics performance in developing countries. Furthermore, the efficient border and trade management, including customs clearance are more critical now Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 14

18) than ever before. Logistics performance is highly related to the dependability of the supply chains and predictability of service available to producers and exporters”.6 In a review of the logistics performance of the countries in the lowest quintile, in which Jamaica is included, timeliness of delivery receives the highest ranking, while customs procedures and quality of logistics services receive the lowest performance marks. This suggests that fulfillment of orders is the most developed portion of the logistics supply chain amongst the lowest country performers. With respect to the Caribbean and Latin American Region, information and communication technology was given the highest rating amongst developing countries, followed by airport and port infrastructure. Rail and road infrastructure received the lowest ratings within the Caribbean and Latin American Region, along with the quality of warehousing. Specific to the customs procedures, the LPI analyses reviewed several functions of the customs performance and compared the performance in these functions between the lowest quintile, in which Jamaica is classified, compared to various higher quintiles. The largest gaps between the performance levels of the lowest quintile countries and the top quintile countries are with respect to onâ€line processing of customs and supporting documentation, online publication of procedures and requirements for export and import, preâ€arrival processing, percent of shipment physically inspected and actual number of physical inspections, the existence of a cooperation among all regulatory agencies, and the development of a single window approach to documentation filing and trade. Such single window systems link the national customs system with numerous governmental agencies. Such a system minimizes the conflicting trade regulations between agencies. With respect to overall delays and service delivery reliability, the lowest ranked countries identified compulsory warehousing, preâ€shipment inspection, criminal activity and 6 Connecting to Compete 2012, Trade Logistics in the Global Economy, The Logistics Performance Index and its Indicators, Jeanâ€Francois Arvis, Monica Alina, Mustra, Lauri Ojala, Ben Shepherd, Daniel Saslavsky, 2012, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 15

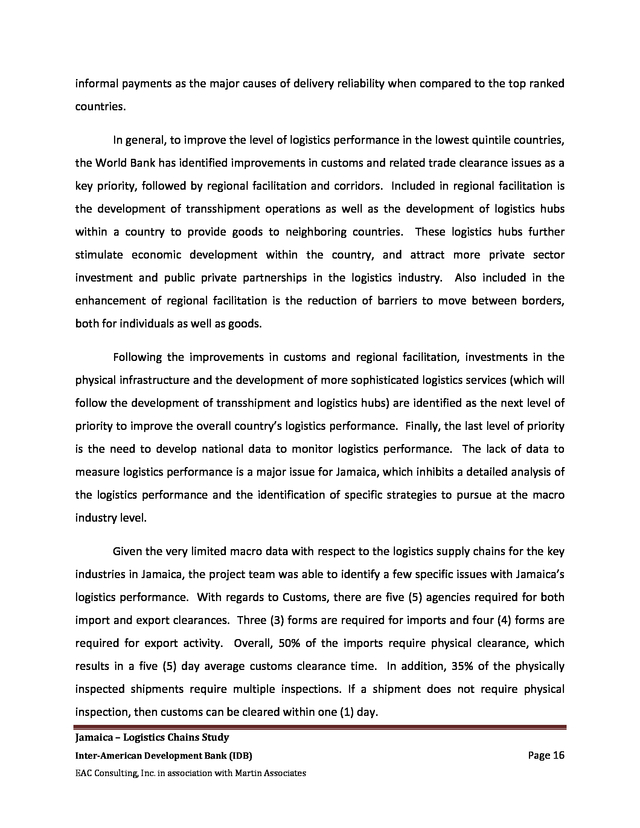

19) informal payments as the major causes of delivery reliability when compared to the top ranked countries. In general, to improve the level of logistics performance in the lowest quintile countries, the World Bank has identified improvements in customs and related trade clearance issues as a key priority, followed by regional facilitation and corridors. Included in regional facilitation is the development of transshipment operations as well as the development of logistics hubs within a country to provide goods to neighboring countries. These logistics hubs further stimulate economic development within the country, and attract more private sector investment and public private partnerships in the logistics industry. Also included in the enhancement of regional facilitation is the reduction of barriers to move between borders, both for individuals as well as goods. Following the improvements in customs and regional facilitation, investments in the physical infrastructure and the development of more sophisticated logistics services (which will follow the development of transshipment and logistics hubs) are identified as the next level of priority to improve the overall country’s logistics performance. Finally, the last level of priority is the need to develop national data to monitor logistics performance. The lack of data to measure logistics performance is a major issue for Jamaica, which inhibits a detailed analysis of the logistics performance and the identification of specific strategies to pursue at the macro industry level. Given the very limited macro data with respect to the logistics supply chains for the key industries in Jamaica, the project team was able to identify a few specific issues with Jamaica’s logistics performance. With regards to Customs, there are five (5) agencies required for both import and export clearances. Three (3) forms are required for imports and four (4) forms are required for export activity. Overall, 50% of the imports require physical clearance, which results in a five (5) day average customs clearance time. In addition, 35% of the physically inspected shipments require multiple inspections. If a shipment does not require physical inspection, then customs can be cleared within one (1) day. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 16

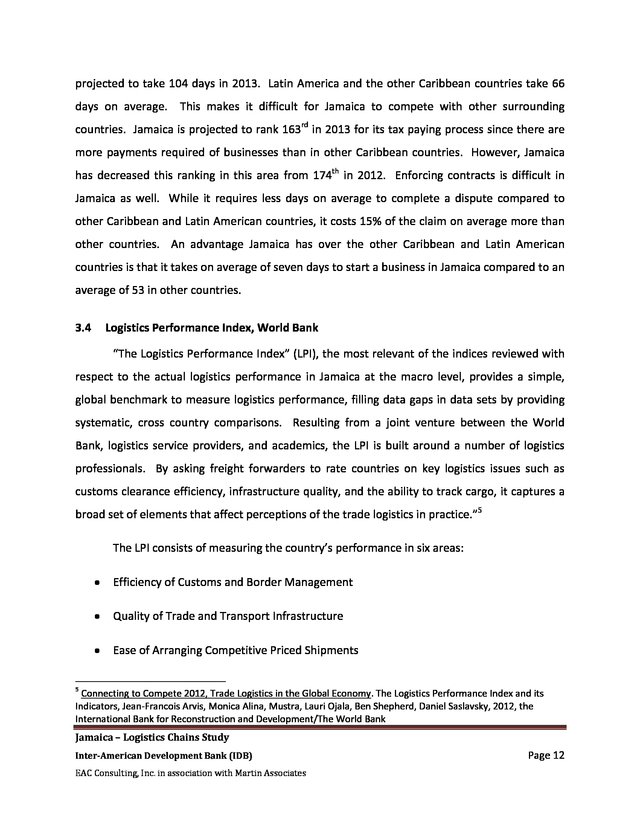

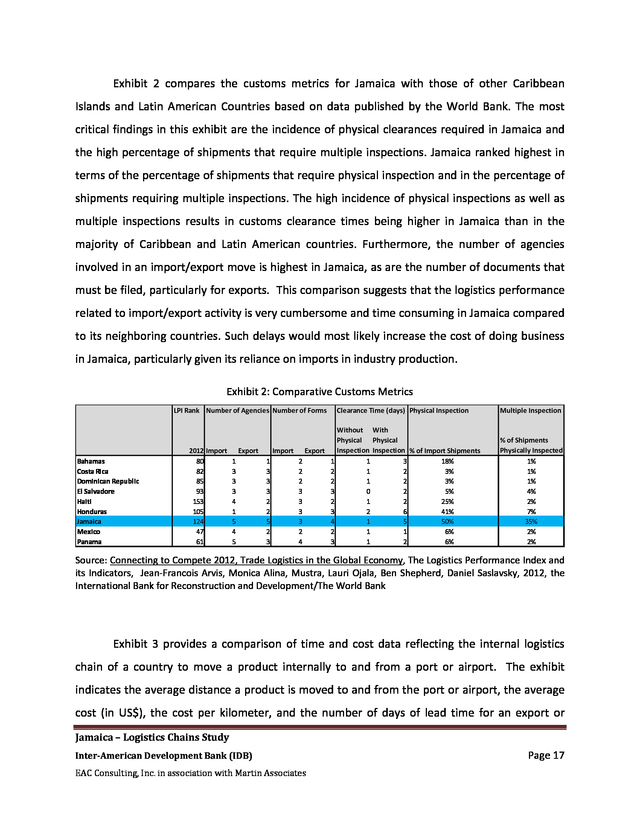

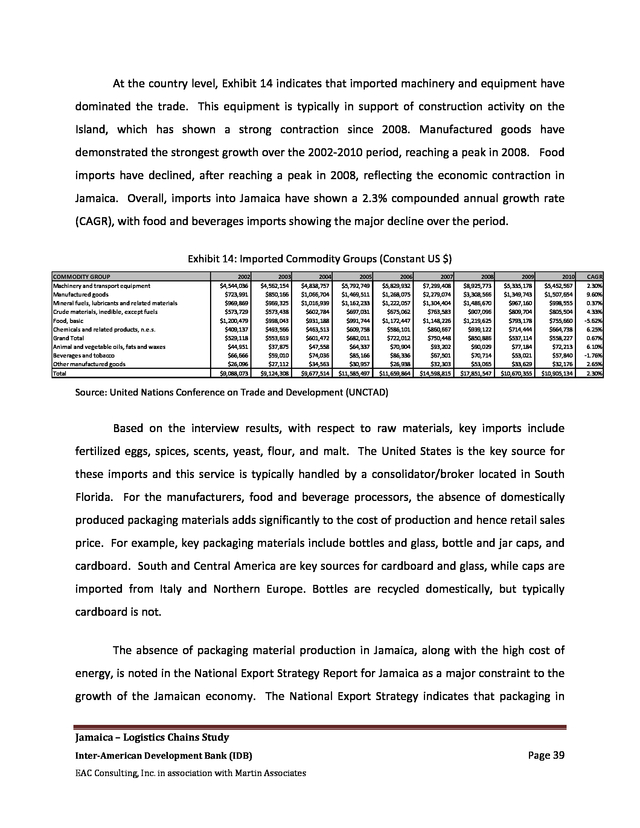

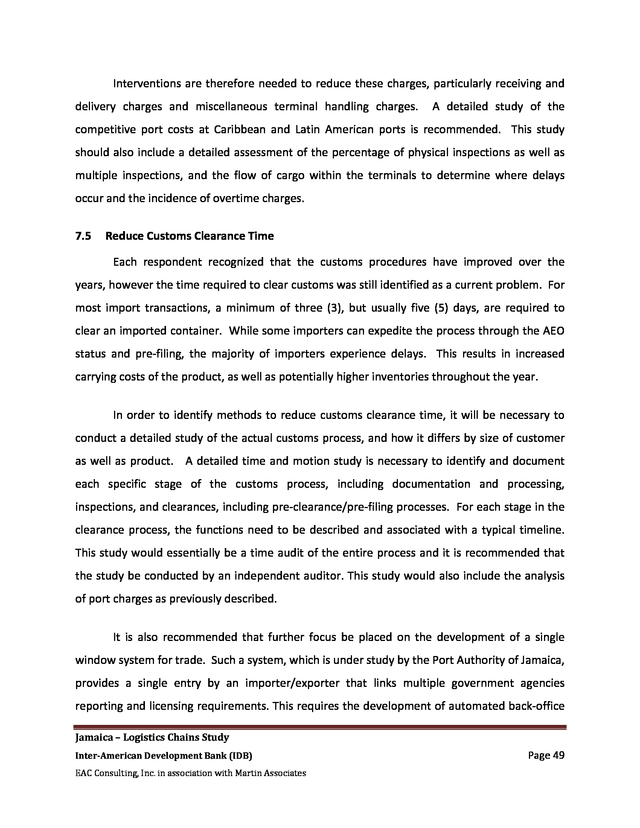

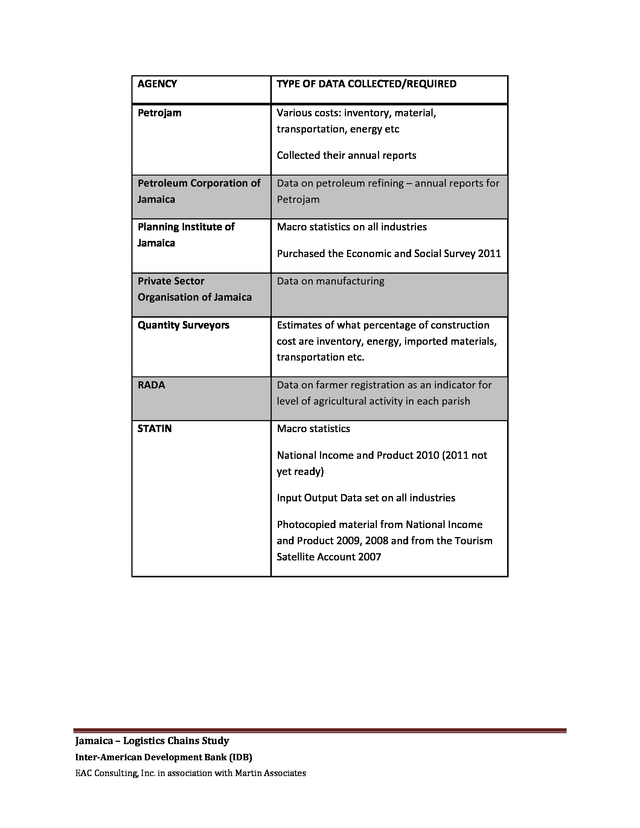

20) Exhibit 2 compares the customs metrics for Jamaica with those of other Caribbean Islands and Latin American Countries based on data published by the World Bank. The most critical findings in this exhibit are the incidence of physical clearances required in Jamaica and the high percentage of shipments that require multiple inspections. Jamaica ranked highest in terms of the percentage of shipments that require physical inspection and in the percentage of shipments requiring multiple inspections. The high incidence of physical inspections as well as multiple inspections results in customs clearance times being higher in Jamaica than in the majority of Caribbean and Latin American countries. Furthermore, the number of agencies involved in an import/export move is highest in Jamaica, as are the number of documents that must be filed, particularly for exports. This comparison suggests that the logistics performance related to import/export activity is very cumbersome and time consuming in Jamaica compared to its neighboring countries. Such delays would most likely increase the cost of doing business in Jamaica, particularly given its reliance on imports in industry production. Exhibit 2: Comparative Customs Metrics LPI Rank Number of Agencies Number of Forms Bahamas Costa Rica Dominican Republic El Salvadore Haiti Honduras Jamaica Mexico Panama 2012 Import 80 82 85 93 153 105 124 47 61 Export 1 3 3 3 4 1 5 4 5 Clearance Time (days) Physical Inspection Without With Physical Physical Inspection Inspection % of Import Shipments Import Export 1 2 1 1 3 18% 3 2 2 1 2 3% 3 2 2 1 2 3% 3 3 3 0 2 5% 2 3 2 1 2 25% 2 3 3 2 6 41% 5 3 4 1 5 50% 2 2 2 1 1 6% 3 4 3 1 2 6% Multiple Inspection % of Shipments Physically Inspected 1% 1% 1% 4% 2% 7% 35% 2% 2% Source: Connecting to Compete 2012, Trade Logistics in the Global Economy, The Logistics Performance Index and its Indicators, Jeanâ€Francois Arvis, Monica Alina, Mustra, Lauri Ojala, Ben Shepherd, Daniel Saslavsky, 2012, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank Exhibit 3 provides a comparison of time and cost data reflecting the internal logistics chain of a country to move a product internally to and from a port or airport. The exhibit indicates the average distance a product is moved to and from the port or airport, the average cost (in US$), the cost per kilometer, and the number of days of lead time for an export or Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 17

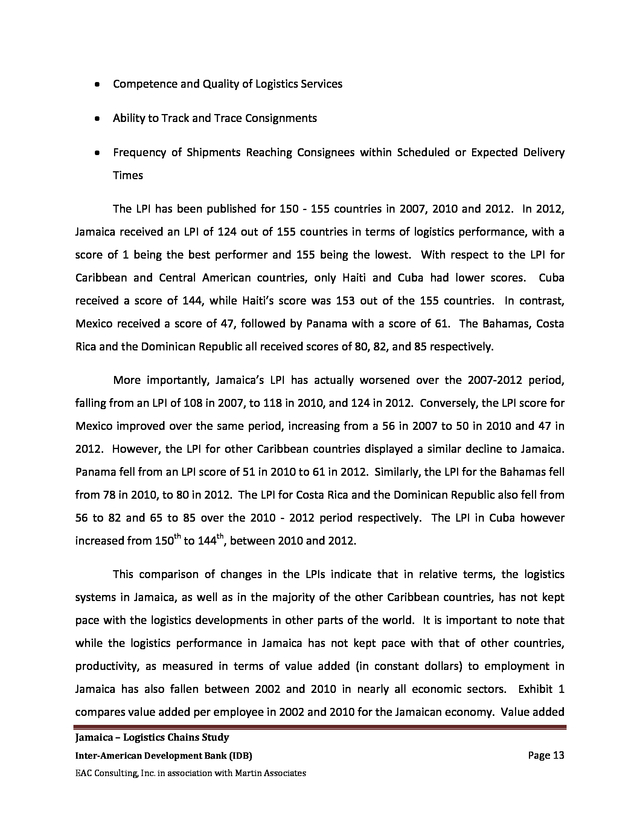

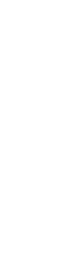

21) import cargo to move to and from a port to an inland location. As presented in the Exhibit, the lead time to move cargo to and from a port to an inland location is significantly greater in Jamaica than for any other neighboring Caribbean Island and Latin American Country based on data published by the World Bank. Haiti is the only other country that comes close to the 14 day lead time required for Jamaica’s import supply chain. In addition, with the exception of the astronomical cost per kilometer to move an export or import cargo to and from the port/airport in the Bahamas, the cost per kilometer is relatively higher in Jamaica when compared to the majority of other countries. Exhibit 3: Time and Cost Involved In Moving Product to and from Airports or Seaports Bahamas Costa Rica Dominican Republic El Salvadore Haiti Honduras Jamaica Mexico Panama LPI Rank Port/Airport Export Supply Chain 2012 Distance Cost Cost/KM Lead Time (days) 80 25 $3,000.00 $120.00 3 82 125 $849.00 $6.79 2 85 43 $500.00 $11.63 2 93 344 $595.00 $1.73 2 153 130 $909.00 $6.99 6 105 52 $500.00 $9.62 3 124 25 $750.00 $30.00 14 47 398 $884.00 $2.22 3 61 36 $383.00 $10.64 2 Port/airport Import Supply Chain Distance Cost Cost/KM Lead Time (days) 25 $2,000.00 $80.00 3 79 $438.00 $5.54 1 43 $500.00 $11.63 2 630 $806.00 $1.28 5 78 $1,587.00 $20.35 12 75 $354.00 $4.72 2 75 $750.00 $10.00 14 352 $1,413.00 $4.01 6 162 $1,310.00 $8.09 3 Source: Connecting to Compete 2012, Trade Logistics in the Global Economy, The Logistics Performance Index and its Indicators, Jeanâ€Francois Arvis, Monica Alina, Mustra, Lauri Ojala, Ben Shepherd, Daniel Saslavsky, 2012, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank In summary, while country specific data is very limited for the logistics industry in Jamaica, it is evident that the customs process and cost of logistics movements within Jamaica are higher than in neighboring countries. In the following section, what limited data and macro research that is available regarding the logistics industry in Jamaica is described. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 18

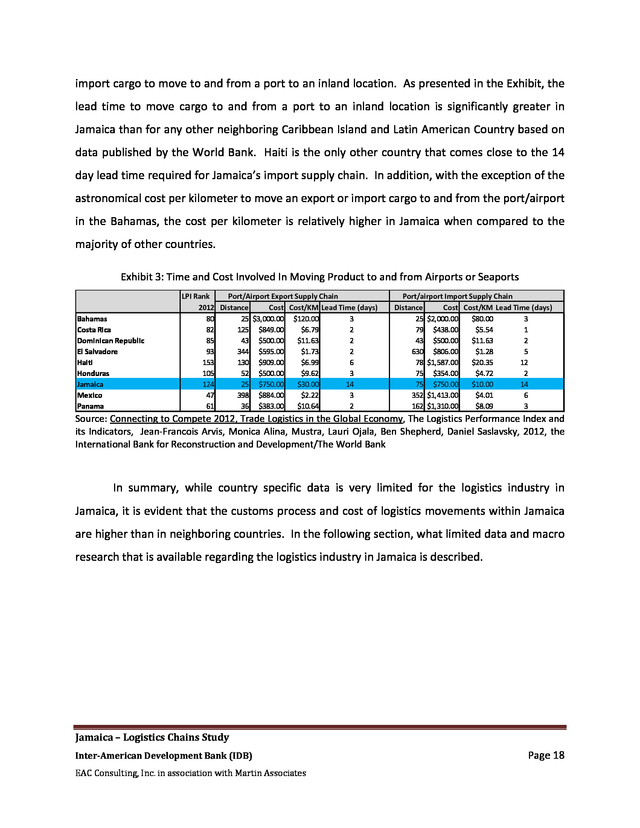

22) 4 Jamaican Logistics Industry at the Macro Level As noted, the absence of national statistical data regarding the logistics performance of Jamaica’s key industries makes it difficult to substantiate assertions that have been made in a limited body of research regarding the country’s supply chain structure. However, the limited research undertaken by the project team indicates that there are three key factors impacting the logistics performance in Jamaica. These are: ï‚· ï‚· Trucking/Road Freight Transportation ï‚· Road Network Concentration of Small and Medium Size Enterprises These factors are consistent with the factors identified by the World Bank Logistics Performance Index.7 4.1 Road Network Because of Jamaica’s geographical location, it is necessary for the roads to withstand natural disasters such as flooding resulting from tropical storms etc. Exhibits 4 and 5 show the highway network infrastructure in Jamaica. Exhibit 4 shows the road map, airports, and ports in Jamaica, while exhibit 5 shows the road network in Jamaica, and the status of the roads in terms of their condition. The Jamaican road network consists of 841 individual roadways, of which 37% are classified as bad and 31% are classified as fair. As shown in the exhibit, many of the roads classified as bad are those connecting Kingston to other areas of the Island. The majority of roads in the Eastern portion of the Island serving St. Thomas, Portland and St. Andrew are also classified as bad, and a similar situation occurs in the northwestern portion of the Island where most roads are classified as bad in the parishes of St. James and Westmoreland. Some of the better roads are 7 Source: Connecting to Compete 2012, Trade Logistics in the Global Economy, The Logistics Performance Index and its Indicators, Jeanâ€Francois Arvis, Monica Alina, Mustra, Lauri Ojala, Ben Shepherd, Daniel Saslavsky, 2012, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 19

23) located within St. Elizabeth, Manchester and Clarendon as well as in the northern portions of St. James, Trelawny, St. Ann, St. Mary and Hanover. This exhibit underscores the need to improve road networks connecting Kingston to other parts of the country. Exhibit 4: Road Network in Jamaica Source: National Works Agency Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 20

24) Exhibit 5: Main Road Condition Survey Source: National Works Agency Investments have been and are currently being made to bring Jamaica’s roads up to a higher level of service. The Government of Jamaica (GOJ) has spent approximately US$160 Million to improve the North Coast Highway, which allows for easier and faster travel from points such as Ocho Rios to Montego Bay, which are the major tourism areas within the island. The GOJ has also spent approximately US$240 million building and upgrading the Portmore Causeway and roads from Kingston to Sandy Bay. The government is currently spending approximately US$105 million from Sandy Bay to May Pen (under construction at the time of producing this report). In order to improve the existing roadway between Kingston to Ocho Rios, the GOJ has spent approximately US $150 million on a new toll road from Linstead to Moneague. In the future, the GOJ will also make additional investments to upgrade the existing roads from Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 21

25) Spanish Town to Linstead and then finally from Moneague to Ocho Rios. The construction of these facilities has not yet been finalized as of the date of this report. In addition, there exists numerous warehouses and distribution centers in the Montego Bay area. The North Coast Highway provides good access to serve the key tourist destinations with retail and hard good items, groceries, sundries and construction materials. The current main highways between Kingston and the North Coast has not had these same improvements and require longer transit times, reducing the location of warehouses and distribution points in these areas. Junction Road, which connects Kingston to Portland, located on the eastern end of the island, also produces very high traffic volumes. While this route can also be used to navigate trips from Kingston to the North Coast, it is a much longer route and navigating the Junction Road is challenging for most visitors to the island. These issues make it difficult for tourists to travel from the resorts along the North Coast to Kingston. With respect to tourism, tourists desire dependent, timely and comfortable transportation. In order to achieve this, there needs to be other improvements to the rural road network, as shown in Exhibit 5. Furthermore, Jamaica needs to differentiate itself from its surrounding islands. This can be done through improvements in health, general services, and adventure and culture tourism. However, it is necessary to make these activities more accessible to tourists by improving the road network. 4.2 Road Freight Transportation The available data on the logistics performance of Jamaica as it related to road freight transportation is very limited. Information presented in chapter 9 of the Growth Inducement Strategy for Jamaica in the Short and Medium Term (2011), provides the most direct information on logistics performance in Jamaica, but underlying statistical data to support the assertions made are not available. This research indicates that there is a high cost per ton to Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 22

26) move goods between production and consumption centers throughout Jamaica.8 This high cost per ton was reflected in the factors underlying the LPI for Jamaica as discussed previously. The World Bank indicated that the cost per kilometer was approximately US$30/km to move export cargo to ports and airports, and about US$10/km to move imports into warehouses and distribution centers near Kingston. However, no national data is available to identify transportation costs as a percentage of value of shipments at the industry level. Because of the high trucking cost per kilometer, it is common for trucks to be overloaded in order to avoid extra trips that save on fuel costs. However, the overloading of trucks causes structural damage to the road pavement which in turn damages the trucks. Recent reductions in weight limits have exacerbated the higher costs associated with trucking operations. There are warehouses throughout the major population hubs in Jamaica; however the literature review indicates that warehousing and distribution facilities are not sufficient due to factors such as the lack of availability of space and flooding, causing them to be inadequate. This in turn causes poor scheduling, delivery compliance, and high product deterioration.9 Exhibit 6 confirms this assertion as the utilization of most warehouses identified by the Factories Corporation of Jamaica, substantiates the high utilization rate, and underscores the need for more warehousing. 8 Hutchinson, Harris, et al. A Growth Inducement Strategy for Jamaica in the Short and Medium Term. 2011 9 Vision 2030 Jamaica, National Development Plan. Planning Institute of Jamaica. 2009 with updates in 2011, Chapter 9 Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 23

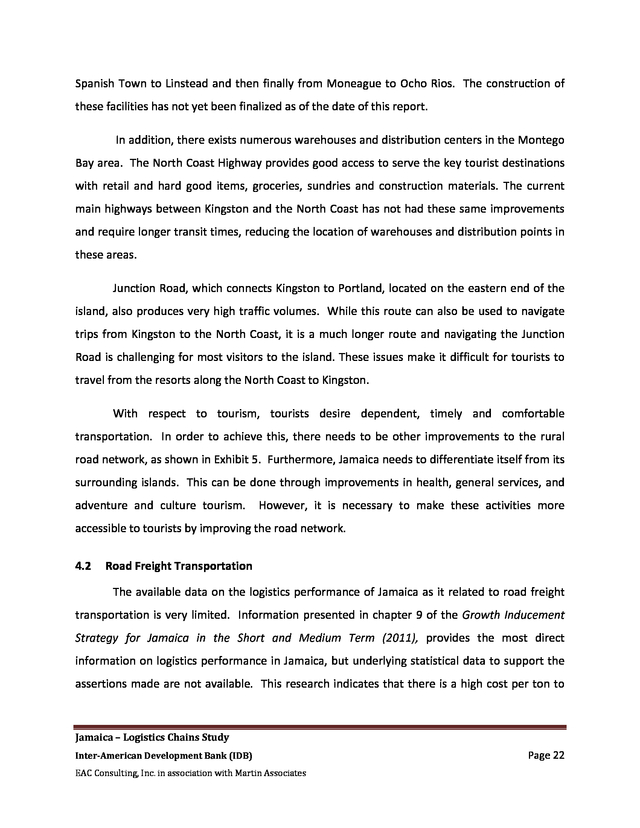

27) Exhibit 6: Warehouse Utilization Rates PARISH/LOCATION TOTAL SPACE sq.ft. OCCUPANCY PARISH/LOCATION Kingston & St. Andrew Torrington ITC Duke St Garmex Free Zone Marcus Garvey Nanse Pen Subâ€Total MANCHESTER 25,735 23,433 603,980 42,282 32,652 728,082 77% 72% 90% 71% 90% 100% 92% 100% 50% 79% 60,000 30,000 120,000 6,372 216,372 67% Hague Industrial Estate 85% NA 0% Sub Total 100% 50% Beach Drive 100% Springfield Albion Estate Eleven Miles Sub â€total 23,273 NA 12,637 NA 35,910 ST. JAMES Montego Bay Freezone Montego Bay Freeport Glendovan SIC Sub Total 240,000 70,100 20,268 330,368 ST. MARY Gibraltar Estate PORTLAND 80% Boundbrook 100% 43% 12,465 24,004 105,173 14,176 155,818 40% 0% 100% 49% 10,000 100% 24,300 100% TRELAWNY 26,400 10,000 36,400 0% 100% 6,552 100% ST. ANN Seville ST. THOMAS 16,000 5,597 21,597 HANOVER 73,744 55,200 9,114 63,000 19,267 220,325 CLARENDON Denbeigh Industrial Estat May Pen Hayes Free Zone Lionel Town Subâ€total Greyground Christiana Subâ€total Karla Haughton Court Sub total ST. CATHERINE Cookson Pen White Marl Central Village Valdez Rd Charelemont SIC Subâ€total TOTAL SPACE TOTAL SPACE sq.ft. sq.ft. OCCUPANCY OCCUPANCY PARISH/LOCATION Source: Factories Corporation of Jamaica The inventory carrying cost for Jamaica is 35% of the GDP, which is significantly higher than the US at only 15% of the GDP.10 The need for adequate warehousing is critical to all manufacturing and agricultural sectors of Jamaica. As indicated in the micro section of this report, participants in the interviews indicated that due to the uncertainty of tropical storms, higher than average inventories must be maintained to prevent logistics supply chain disruptions. This results in a high cost of inventory. These costs are seen in factors accompanying increased inventory, such as the need for additional space to handle this inventory, increased spoilage rates, and increased operating costs associated with maintaining a larger facility. 10 Vision 2030 Jamaica, National Development Plan. Planning Institute of Jamaica. 2009 with updates in 2011 Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 24

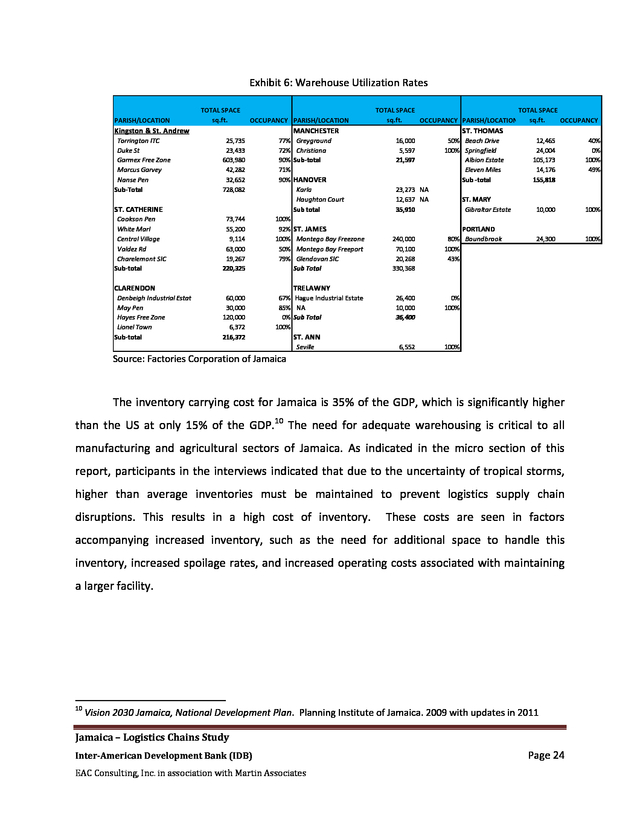

28) 4.3 Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Supply Chain Management and Logistics The literature review indicates that the majority of businesses in Jamaica are considered small and medium size enterprises, with 45% having less than 10 employees. These smaller companies do not have the same leverage in supply chain optimization as their larger counterparts, and therefore they have higher freight logistics costs. On average, SMEs have smaller load sizes, less access to warehousing, and a lack of expertise that large businesses can acquire. Furthermore, there is an increasing shortage of warehouse capacity in the agricultural sector, which commonly requires refrigerated or special warehouse space. Since a large portion of the companies in Jamaica are agriculturally related, this shortage of warehouse capacity was identified in the literature as an increasing problem. 11 The infrastructure and logistical characteristics of the SMEs directly affect several sectors, especially agriculture. Key factors affecting this sector include the cost of production, reliability, quality of produce, and delivery to major markets. Key agricultural production centers are located in Trelawny, St. Elizabeth and Manchester. There is the potential for local agricultural companies to increase their supplies to tourism centers, but the literature review has indicated that delivery dependability has been an issue. However, no statistics are available at the industry level to identify the degree of fulfillment failures in the delivery of agricultural products. Furthermore, transportation costs and issues related to timely deliveries to the main consumption points impacts the ability of the agricultural sector to efficiently serve the tourism sector. This finding, however, was not substantiated by the results of interviews with logistics managers of the country’s leading manufacturers and services providers, as discussed in following section of this report. 11 Hutchinson, Harris, et al. A Growth Inducement Strategy for Jamaica in the Short and Medium Term. 2011 Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 25

29) In summary, logistics systems create efficiencies in agriculture by bringing rural communities within the reach of their domestic and export markets. However, rural roads need to be improved to help create access to these markets. In addition, logistics training in these rural areas is necessary to improve harvesting techniques. This will increase the shelf life, reduce farmâ€to market losses, and create a network of modern storage and warehouse activities. Communication is also important for the logistics systems to function well because it will allow companies to receive orders, deliver product, process deliveries on time, and ultimately make more dependable and predictable deliveries. Better communication also allows for companies to be able to more accurately match truck sizes with orders, increasing efficiency while reducing excess cost. Due to the absence of national statistical data regarding logistics performance, the remaining analyses are based on the results of interviews with the logistics managers of the country’s leading industrial, tourism, construction/mining and agricultural sector firms. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 26

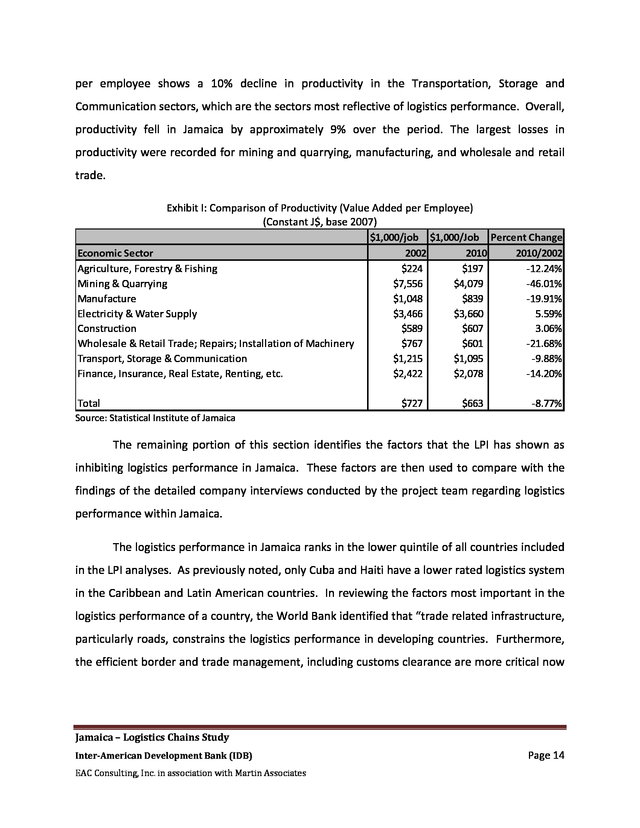

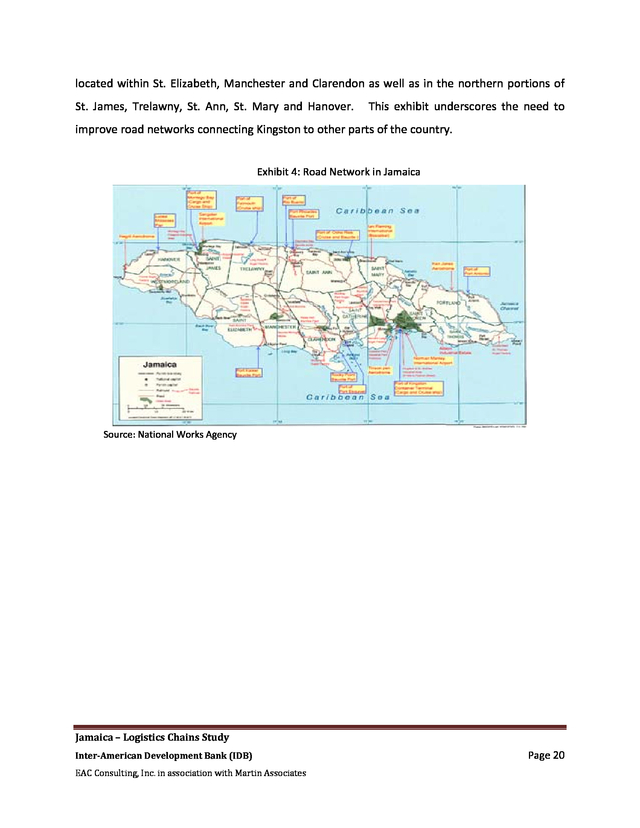

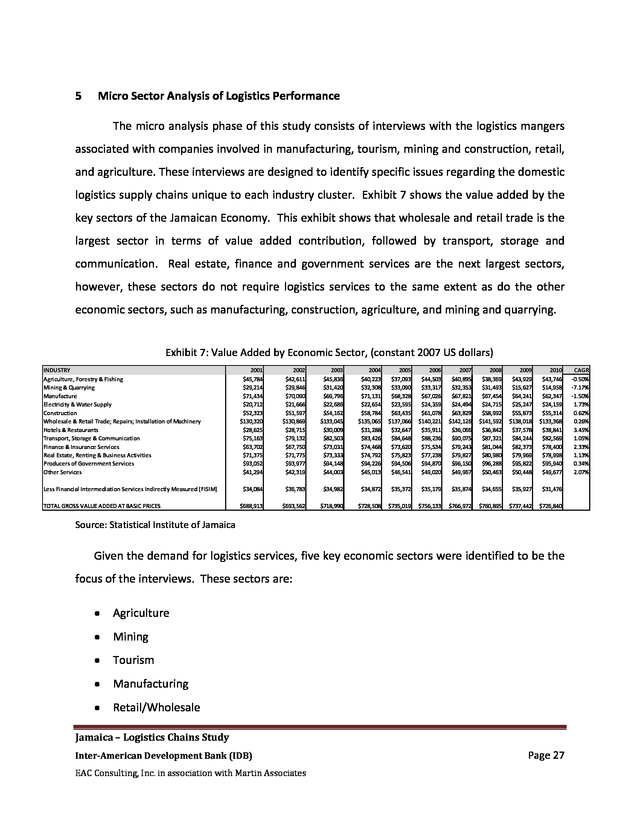

30) 5 Micro Sector Analysis of Logistics Performance The micro analysis phase of this study consists of interviews with the logistics mangers associated with companies involved in manufacturing, tourism, mining and construction, retail, and agriculture. These interviews are designed to identify specific issues regarding the domestic logistics supply chains unique to each industry cluster. Exhibit 7 shows the value added by the key sectors of the Jamaican Economy. This exhibit shows that wholesale and retail trade is the largest sector in terms of value added contribution, followed by transport, storage and communication. Real estate, finance and government services are the next largest sectors, however, these sectors do not require logistics services to the same extent as do the other economic sectors, such as manufacturing, construction, agriculture, and mining and quarrying. Exhibit 7: Value Added by Economic Sector, (constant 2007 US dollars) INDUSTRY Agriculture, Forestry & Fishing Mining & Quarrying Manufacture Electricity & Water Supply Construction Wholesale & Retail Trade; Repairs; Installation of Machinery Hotels & Restaurants Transport, Storage & Communication Finance & Insurance Services Real Estate, Renting & Business Activities Producers of Government Services Other Services Less Financial Intermediation Services Indirectly Measured (FISIM) TOTAL GROSS VALUE ADDED AT BASIC PRICES 2001 $45,784 $29,214 $71,434 $20,712 $52,323 $130,320 $28,625 $75,163 $63,702 $71,375 $93,052 $41,294 2002 $42,611 $29,846 $70,090 $21,666 $51,597 $130,869 $28,715 $79,132 $67,750 $71,775 $93,977 $42,319 $34,084 $36,783 $688,913 2003 $45,836 $31,420 $69,796 $22,686 $54,162 $133,045 $30,009 $82,503 $73,031 $73,333 $94,148 $44,003 2004 $40,223 $32,308 $71,131 $22,654 $58,784 $135,065 $31,288 $83,426 $74,468 $74,792 $94,226 $45,013 $34,982 $693,562 2006 $44,503 $33,317 $67,026 $24,359 $61,078 $140,221 $35,911 $88,236 $75,534 $77,238 $94,870 $49,020 $35,372 $35,179 $34,872 $718,990 2005 $37,093 $33,090 $68,328 $23,595 $63,435 $137,066 $32,647 $84,648 $73,620 $75,823 $94,506 $46,541 $728,508 2007 $40,895 $32,353 $67,821 $24,494 $63,829 $142,126 $36,066 $90,075 $79,243 $79,827 $96,150 $49,967 $735,019 $35,874 $756,133 2008 $38,369 $31,493 $67,454 $24,715 $58,992 $141,592 $36,842 $87,321 $81,044 $80,980 $96,288 $50,463 $34,655 $766,972 2009 $43,929 $15,627 $64,241 $25,247 $55,873 $138,018 $37,578 $84,244 $82,373 $79,969 $95,822 $50,448 $31,476 $737,442 $726,840 Source: Statistical Institute of Jamaica Given the demand for logistics services, five key economic sectors were identified to be the focus of the interviews. These sectors are: ï‚· Agriculture ï‚· Mining ï‚· Tourism ï‚· Manufacturing ï‚· Retail/Wholesale Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates CAGR â€0.50% â€7.17% â€1.50% 1.73% 0.62% 0.26% 3.45% 1.05% 2.33% 1.13% 0.34% 2.07% $35,927 $760,895 2010 $43,746 $14,958 $62,347 $24,159 $55,314 $133,368 $38,841 $82,569 $78,400 $78,998 $95,940 $49,677 Page 27

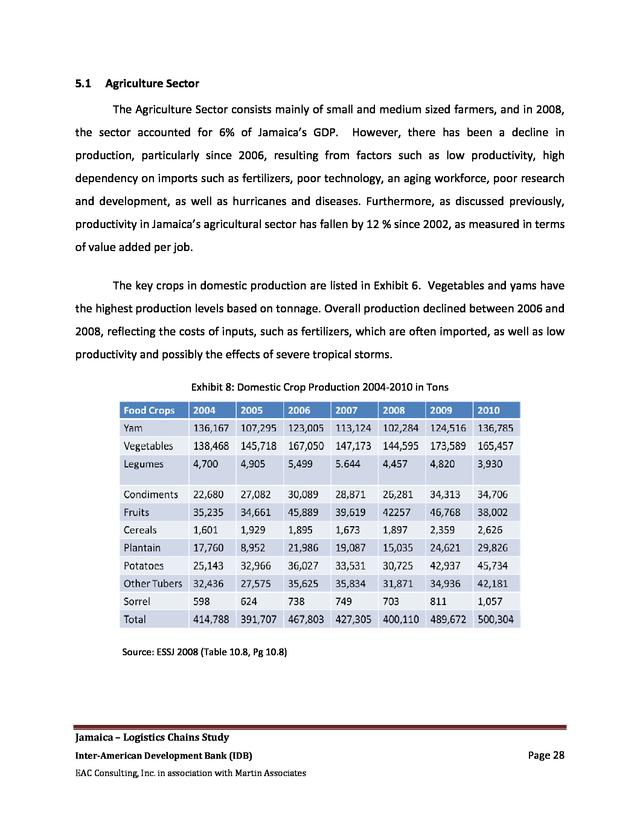

31) 5.1 Agriculture Sector The Agriculture Sector consists mainly of small and medium sized farmers, and in 2008, the sector accounted for 6% of Jamaica’s GDP. However, there has been a decline in production, particularly since 2006, resulting from factors such as low productivity, high dependency on imports such as fertilizers, poor technology, an aging workforce, poor research and development, as well as hurricanes and diseases. Furthermore, as discussed previously, productivity in Jamaica’s agricultural sector has fallen by 12 % since 2002, as measured in terms of value added per job. The key crops in domestic production are listed in Exhibit 6. Vegetables and yams have the highest production levels based on tonnage. Overall production declined between 2006 and 2008, reflecting the costs of inputs, such as fertilizers, which are often imported, as well as low productivity and possibly the effects of severe tropical storms. Exhibit 8: Domestic Crop Production 2004â€2010 in Tons Source: ESSJ 2008 (Table 10.8, Pg 10.8) Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 28

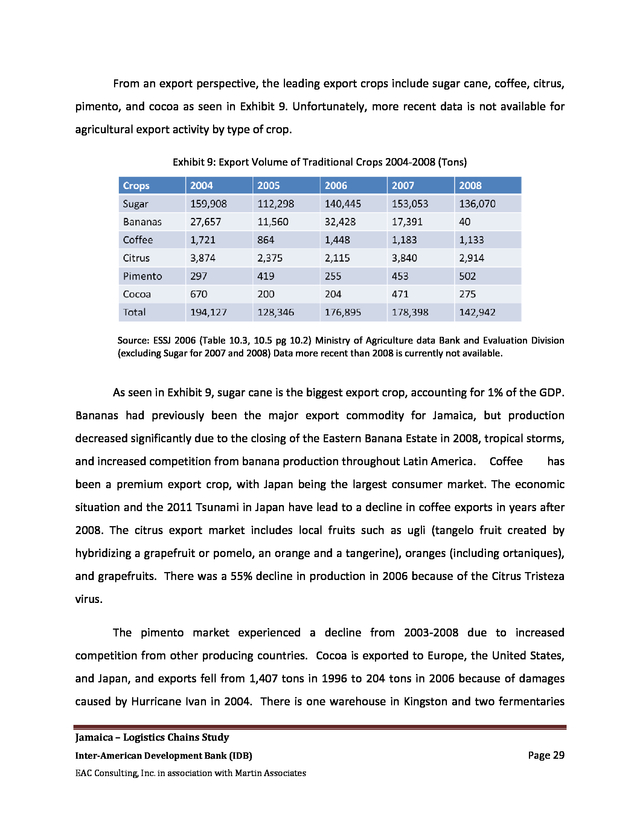

32) From an export perspective, the leading export crops include sugar cane, coffee, citrus, pimento, and cocoa as seen in Exhibit 9. Unfortunately, more recent data is not available for agricultural export activity by type of crop. Exhibit 9: Export Volume of Traditional Crops 2004â€2008 (Tons) Source: ESSJ 2006 (Table 10.3, 10.5 pg 10.2) Ministry of Agriculture data Bank and Evaluation Division (excluding Sugar for 2007 and 2008) Data more recent than 2008 is currently not available. As seen in Exhibit 9, sugar cane is the biggest export crop, accounting for 1% of the GDP. Bananas had previously been the major export commodity for Jamaica, but production decreased significantly due to the closing of the Eastern Banana Estate in 2008, tropical storms, and increased competition from banana production throughout Latin America. Coffee has been a premium export crop, with Japan being the largest consumer market. The economic situation and the 2011 Tsunami in Japan have lead to a decline in coffee exports in years after 2008. The citrus export market includes local fruits such as ugli (tangelo fruit created by hybridizing a grapefruit or pomelo, an orange and a tangerine), oranges (including ortaniques), and grapefruits. There was a 55% decline in production in 2006 because of the Citrus Tristeza virus. The pimento market experienced a decline from 2003â€2008 due to increased competition from other producing countries. Cocoa is exported to Europe, the United States, and Japan, and exports fell from 1,407 tons in 1996 to 204 tons in 2006 because of damages caused by Hurricane Ivan in 2004. There is one warehouse in Kingston and two fermentaries Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 29

33) (St. Mary and Clarendon) to handle the cocoa.12 Coconuts are no longer exported and are mostly produced for local use. These are predominantly grown in the Parishes of St. Thomas, St. Mary, Portland, St. Ann, and St. Catherine. Since 2001, overall value added in agricultural production has declined at an average annual rate of 0.5%. Overall, agricultural production value reached a peak in 2003, then again nearly regained that level in 2006. However, since 2006, the value added in agriculture and forestry has lagged previous performance. This is at least in part due to hurricane and strong tropical storm activities between 2006 and 2008. Between October and December 2011, the Agricultural Sector grew by 16.4%, which is largely due to replanting, following Tropical Storm Nicole and the Ministry of Agriculture’s Production and Productivity Program, which works to improve bestâ€practice methods used by farmers. The program provides information on methods to mitigate against occurrences such as drought by using water conservation practices, increased planting in areas that have irrigation systems, and increasing the use of greenhouses.13 However, exports of agricultural products fell by 0.7% during the period of October to December 2011.14 5.2 Mining Industry Sector The Mining Industry in Jamaica consists primarily of bauxite, alumina, and limestone, which accounted for 2% of the Jamaican GDP in 2010. In 2008, Jamaica was the 6th largest producer of bauxite and alumina in the world. The country supplies over one third of the total bauxite imports and 10% of alumina imports into the United States. The industry is highly concentrated. For example, one bauxite producer exports about 5.3 million tons per year, primarily to the United States. Similarly, the alumina production is also highly concentrated, as three alumina producers account for about four million tons per year, and these producers 12 Vision 2030 Jamaica Agriculture Sector Plan. Agriculture Task Force. Sept 2009. 13 Hutchinson, Harris, et al. A Growth Inducement Strategy for Jamaica in the Short and Medium Term. 2011 14 Review of Economic Performance: Octoberâ€December 2011. Planning Institute of Jamaica. 23 Feb 2012. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 30

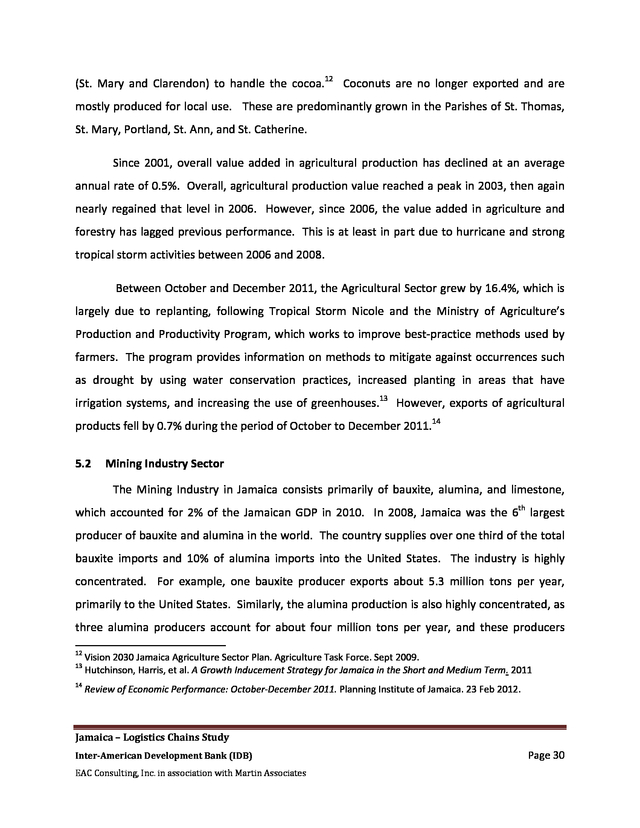

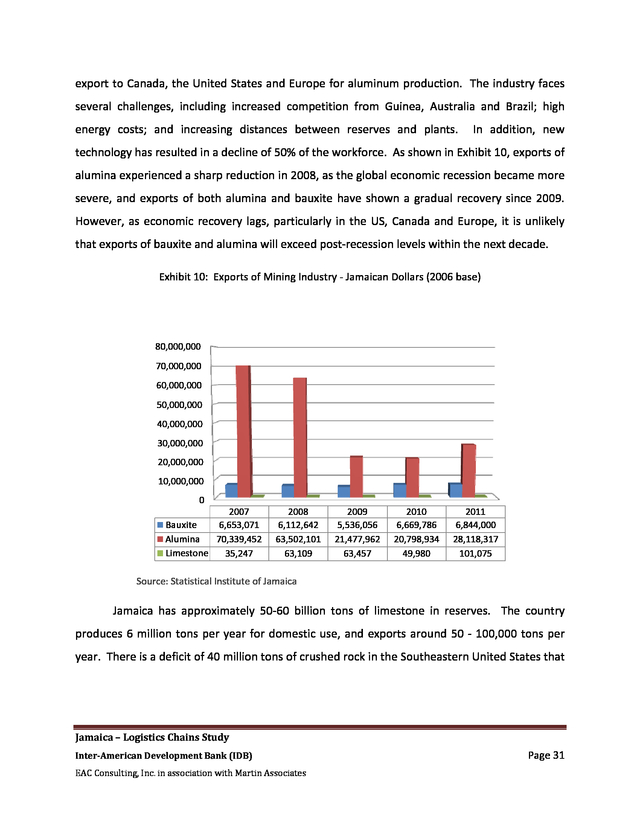

34) export to Canada, the United States and Europe for aluminum production. The industry faces several challenges, including increased competition from Guinea, Australia and Brazil; high energy costs; and increasing distances between reserves and plants. In addition, new technology has resulted in a decline of 50% of the workforce. As shown in Exhibit 10, exports of alumina experienced a sharp reduction in 2008, as the global economic recession became more severe, and exports of both alumina and bauxite have shown a gradual recovery since 2009. However, as economic recovery lags, particularly in the US, Canada and Europe, it is unlikely that exports of bauxite and alumina will exceed postâ€recession levels within the next decade. Exhibit 10: Exports of Mining Industry †Jamaican Dollars (2006 base) 80,000,000 70,000,000 60,000,000 50,000,000 40,000,000 30,000,000 20,000,000 10,000,000 0 2007 Bauxite 6,653,071 Alumina 70,339,452 Limestone 35,247 2008 6,112,642 63,502,101 63,109 2009 5,536,056 21,477,962 63,457 2010 6,669,786 20,798,934 49,980 2011 6,844,000 28,118,317 101,075 Source: Statistical Institute of Jamaica Jamaica has approximately 50â€60 billion tons of limestone in reserves. The country produces 6 million tons per year for domestic use, and exports around 50 †100,000 tons per year. There is a deficit of 40 million tons of crushed rock in the Southeastern United States that Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 31

35) provides a longer term potential for export opportunities.15 The location of the Bauxite mines and operations and ports are shown in Exhibit 11. Bauxite is typically moved to the ports by rail and extensive conveyor belt systems. Exhibit 11: Location of Bauxite Mines Source: Jamaica Bauxite Institute Overall, the mining and quarry industry in Jamaica has experienced a significant contraction. Over the past 9 years, the value added in this industry has declined by 50%, reflecting the reduced demand for exports of bauxite and alumina, driven by the world’s economic recession. However, between October and December 2011, the mining and quarrying industry grew overall by 8.2%. This was a result of the Windalco Ewarton Aluminum Plant reopening, and an increase in production at Nordanaa Bauxite.16 15 National Export Strategy. Rep. Kingston: Ministry of Industry Investment & Commerce, 2009. 16 Review of Economic Performance: Octoberâ€December 2011. Planning Institute of Jamaica. 23 Feb 2012. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 32

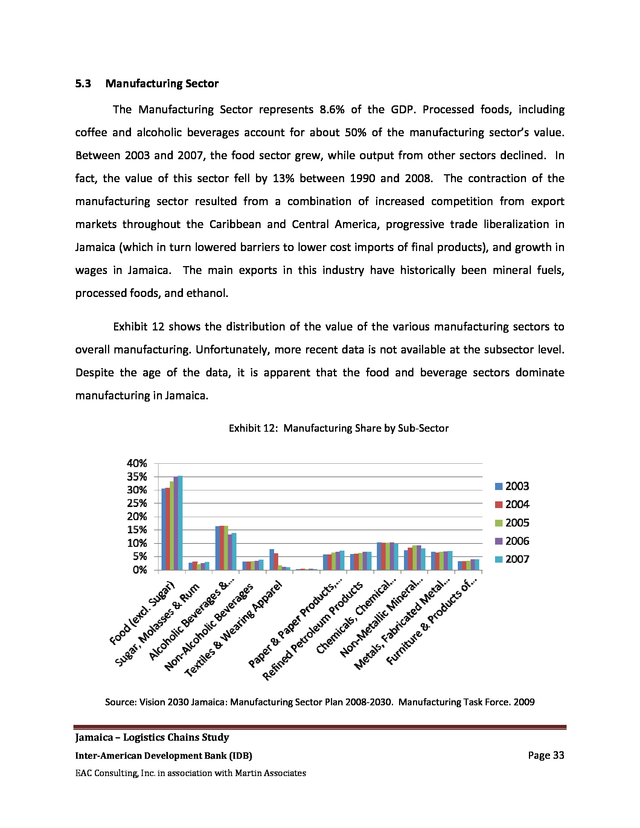

36) 5.3 Manufacturing Sector The Manufacturing Sector represents 8.6% of the GDP. Processed foods, including coffee and alcoholic beverages account for about 50% of the manufacturing sector’s value. Between 2003 and 2007, the food sector grew, while output from other sectors declined. In fact, the value of this sector fell by 13% between 1990 and 2008. The contraction of the manufacturing sector resulted from a combination of increased competition from export markets throughout the Caribbean and Central America, progressive trade liberalization in Jamaica (which in turn lowered barriers to lower cost imports of final products), and growth in wages in Jamaica. The main exports in this industry have historically been mineral fuels, processed foods, and ethanol. Exhibit 12 shows the distribution of the value of the various manufacturing sectors to overall manufacturing. Unfortunately, more recent data is not available at the subsector level. Despite the age of the data, it is apparent that the food and beverage sectors dominate manufacturing in Jamaica. Exhibit 12: Manufacturing Share by Subâ€Sector Source: Vision 2030 Jamaica: Manufacturing Sector Plan 2008â€2030. Manufacturing Task Force. 2009 Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 33

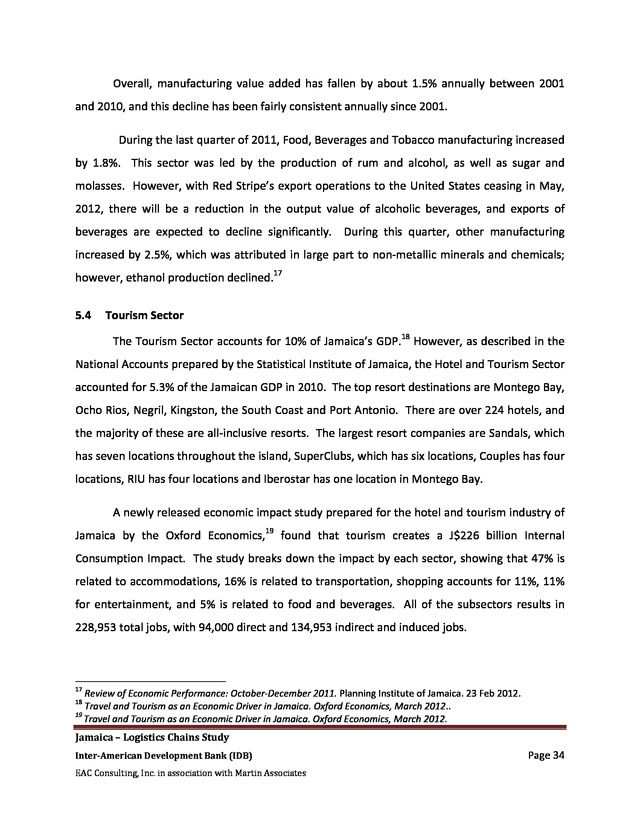

37) Overall, manufacturing value added has fallen by about 1.5% annually between 2001 and 2010, and this decline has been fairly consistent annually since 2001. During the last quarter of 2011, Food, Beverages and Tobacco manufacturing increased by 1.8%. This sector was led by the production of rum and alcohol, as well as sugar and molasses. However, with Red Stripe’s export operations to the United States ceasing in May, 2012, there will be a reduction in the output value of alcoholic beverages, and exports of beverages are expected to decline significantly. During this quarter, other manufacturing increased by 2.5%, which was attributed in large part to nonâ€metallic minerals and chemicals; however, ethanol production declined.17 5.4 Tourism Sector The Tourism Sector accounts for 10% of Jamaica’s GDP.18 However, as described in the National Accounts prepared by the Statistical Institute of Jamaica, the Hotel and Tourism Sector accounted for 5.3% of the Jamaican GDP in 2010. The top resort destinations are Montego Bay, Ocho Rios, Negril, Kingston, the South Coast and Port Antonio. There are over 224 hotels, and the majority of these are allâ€inclusive resorts. The largest resort companies are Sandals, which has seven locations throughout the island, SuperClubs, which has six locations, Couples has four locations, RIU has four locations and Iberostar has one location in Montego Bay. A newly released economic impact study prepared for the hotel and tourism industry of Jamaica by the Oxford Economics,19 found that tourism creates a J$226 billion Internal Consumption Impact. The study breaks down the impact by each sector, showing that 47% is related to accommodations, 16% is related to transportation, shopping accounts for 11%, 11% for entertainment, and 5% is related to food and beverages. All of the subsectors results in 228,953 total jobs, with 94,000 direct and 134,953 indirect and induced jobs. 17 Review of Economic Performance: Octoberâ€December 2011. Planning Institute of Jamaica. 23 Feb 2012. 18 Travel and Tourism as an Economic Driver in Jamaica. Oxford Economics, March 2012.. 19 Travel and Tourism as an Economic Driver in Jamaica. Oxford Economics, March 2012. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 34

38) Since 2001, the value added in the tourism sector has grown at an average annual growth rate of about 3.45%, reflecting the strongest sector in the Jamaican economy. Total visitor arrivals have grown from a low of 2.7 million visitor arrivals to 3.1 million in 2011. This growth has been driven by the growth in stopâ€over visits. While cruise passenger arrivals fell from a high of 1.3 million in 200620, there has been a slow increase of passengers over the past five years, reaching 1.1 million in 2011. This is largely a result of the construction of the Falmouth Pier, which provides additional berth space for new cruise liners. Added cruise liners should in turn result in increased passenger arrivals. 21 5.5 Retail and Wholesale Sector The retail and wholesale sector accounts for about 18% of the Jamaican GDP and has shown an average annual growth rate of less than 1% annual since 2001. Productivity, measured in terms of value added per job has fallen by more than 21% in this economic cluster between 2002 and 2010. 20 Vision 2030 Jamaica Tourism Sector Plan. Tourism Task Force Sept 2009. 21 Jackson, Steven. “Jamaica Now Fastest Growing Regional Cruise Market.” The Gleaner 29 Feb 2012. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 35

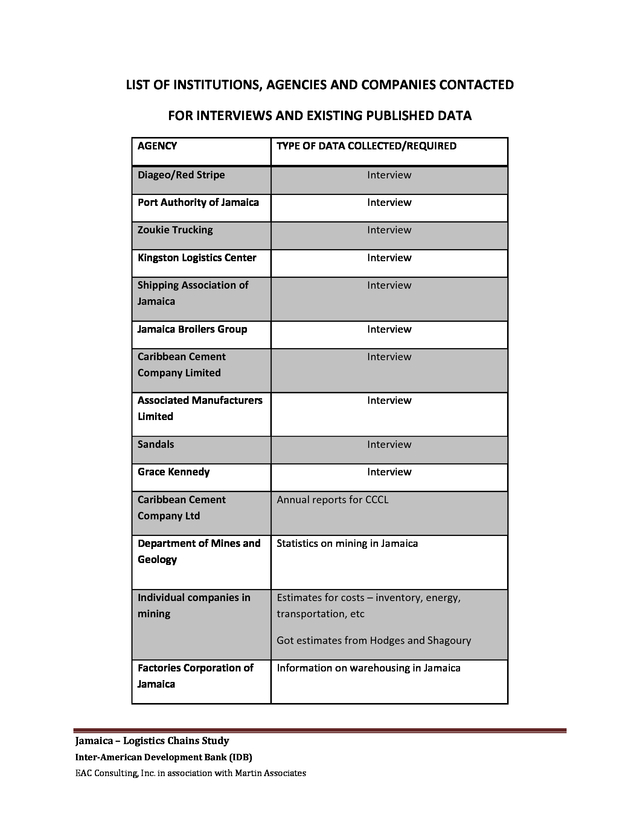

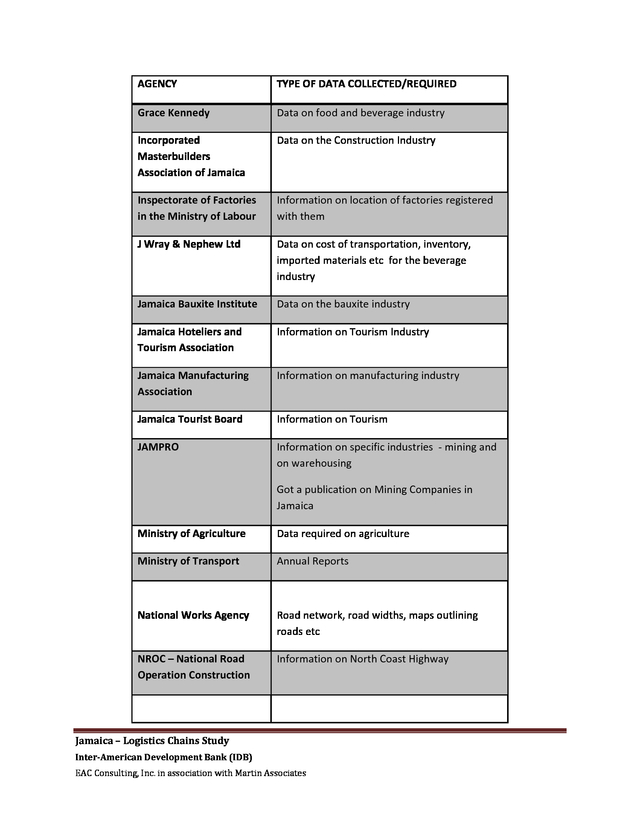

39) 6 Micro Level Analysis – Interviews The project team conducted detailed interviews with the logistics managers of the key firms in each of the six economic sectors to identify logistical issues impacting the distribution of goods throughout Jamaica. In addition, logistical issues were examined that potentially impact the competitive position of the Jamaican industry in the world economy, as well as limiting internal economic growth.22 Based on these interviews, a series of recommendations were developed to address the identified logistics constraints, and to stimulate economic growth within the country. The project team conducted interviews with the logistics managers of the following firms: ï‚· Diageo/Red Stripe (Food and Beverage Sector) ï‚· Port Authority of Jamaica (Port Facilities, Storage and Warehousing Sector) ï‚· Zoukie Trucking (Transportation Sector) ï‚· Kingston Logistics Center (Transportation, Storage and Warehousing Sector) ï‚· Shipping Association of Jamaica (Transportation, Storage and Warehousing Sector) ï‚· Jamaican Boilers Group of Companies (Manufacturing/Agricultural/Retail and Wholesale Sectors) ï‚· Caribbean Cement Company Limited (Mining/Construction Sector) ï‚· Associated Manufactures Limited (Manufacturing/Food/Agricultural Sectors) ï‚· Sandals (Tourism Sector) ï‚· Grace Kennedy (Retail and Wholesale/Manufacturing/Agricultural Sectors) These companies are representative of the key industry sectors identified, which are manufacturing, tourism, agriculture, retail/wholesale, construction and mining. It is to be emphasized that these companies also represent several other manufacturers and lines of businesses within Jamaica. The interview guide used during the interview process is included as Appendix A. Specific responses received by each interviewee are intentionally 22 Due to limited budget, interviews with small business enterprises could not be conducted and would be included in a larger scale study to develop detailed lgostics data base for the Country’s industry clusters. Jamaica – Logistics Chains Study Interâ€American Development Bank (IDB) EAC Consulting, Inc. in association with Martin Associates Page 36