1) A Study to Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location in the Caribbean Region Final Report By Nanyang Technological University (Singapore) 2013

2) Contents List of Tables List of Figures List of Abbreviations and Acronyms Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Purpose and Description of the Project 3. Economic Impact Analysis and Market Assessment 3.1 Economic impact analysis 3.1.1 Overview of current bunkering operations in Jamaica 3.1.2 Direct value added 3.1.3 Indirect value added 3.1.4 Induced value added and linkage between bunkering activities and overall economy 3.2 State of competition and commercial parameters 3.2.1 State of competition in the bunkering industry in Jamaica and the wider Caribbean and American region 3.2.2 Emerging competition to note 3.2.3 Competitiveness of current bunker supply and service providers in Jamaica 3.3 Demand conditions and market dynamics 3.3.1 Size of demand 3.3.2 Composition of demand 3.3.3 Drivers of demand and accompanying trends and development 3.3.4 Sophistication of demand 3.3.5 Captive demand 3.4 Government policy and interaction 3.4.1 Relevant government policies that affect the competitiveness and commercial viability of the bunkering sector in Jamaica 3.4.2 Policies pursued in competing bunkering centres 3.4.2.1 Freeport Bahamas 3.4.2.2 Cartagena Colombia 3.4.2.3 Panama 3.4.2.4 Puerto Rico 3.4.2.5 Suriname 3.4.2.6 Trinidad and Tobago 3.5 Bunkering demand forecast 3.5.1 Basis of demand forecast 3.5.2 Scenario of steady growth 3.5.3 High growth scenario 3.5.4 Low growth scenario 3.5.5 Summary of demand forecasts Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page 6 7 8 10 18 18 19 19 20 21 24 25 27 27 28 29 30 30 31 32 33 34 34 34 36 36 36 37 37 37 38 38 38 41 43 44 45 Page | 1

3) 4. Environment Scan, Competitive Advantage Analysis and Competition Study 4.1 Environment scan 4.1.1 Macroeconomic developments 4.1.2 Ship operators’ attitudes, trends and requirements 4.1.3 Political, regulatory and policy trends 4.1.4 Shipping industry trends, conditions and consolidation 4.1.5 Shipping technology progression 4.2 Competitive advantage analysis 4.2.1 Factor conditions 4.2.2 Demand conditions 4.2.3 Company strategy, firm structure and industry rivalry 4.2.4 Related and supporting activities 4.2.5 Government policies 4.2.6 Chance events 4.3 Benchmarking with regional and international bunkering markets 4.3.1 Jamaica 4.3.1.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.1.2 Sales volumes 4.3.1.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.1.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.1.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.1.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.1.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.3.2 Bahamas – Freeport 4.3.2.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.2.2 Sales volumes 4.3.2.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.2.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.2.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.2.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.2.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.3.3 Colombia – Cartagena 4.3.3.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.3.2 Sales volumes 4.3.3.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.3.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.3.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.3.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.3.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.3.4 Panama Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location 48 48 48 49 51 52 54 59 60 62 64 65 66 66 67 71 71 71 71 72 72 73 73 75 75 75 77 77 77 78 78 79 79 79 79 80 80 81 82 82 Page | 2

4) 4.3.4.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.4.2 Sales volumes 4.3.4.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.4.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.4.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.4.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.4.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.3.5 Puerto Rico 4.3.5.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.5.2 Sales volumes 4.3.5.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.5.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.5.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.5.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.5.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.3.6 Suriname 4.3.6.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.6.2 Sales volumes 4.3.6.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.6.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.6.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.6.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.6.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.3.7 Trinidad & Tobago 4.3.7.1 Bunker suppliers 4.3.7.2 Sales volumes 4.3.7.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.7.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.7.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.7.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.7.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.3.8 Houston 4.3.8.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.8.2 Sales volumes 4.3.8.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.8.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.8.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.8.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.8.7 Strategies in relation to value creation Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location 82 82 84 84 85 86 86 87 87 87 88 88 89 89 90 90 90 90 90 91 91 91 92 92 92 92 93 93 93 94 94 94 94 95 95 95 95 96 96 Page | 3

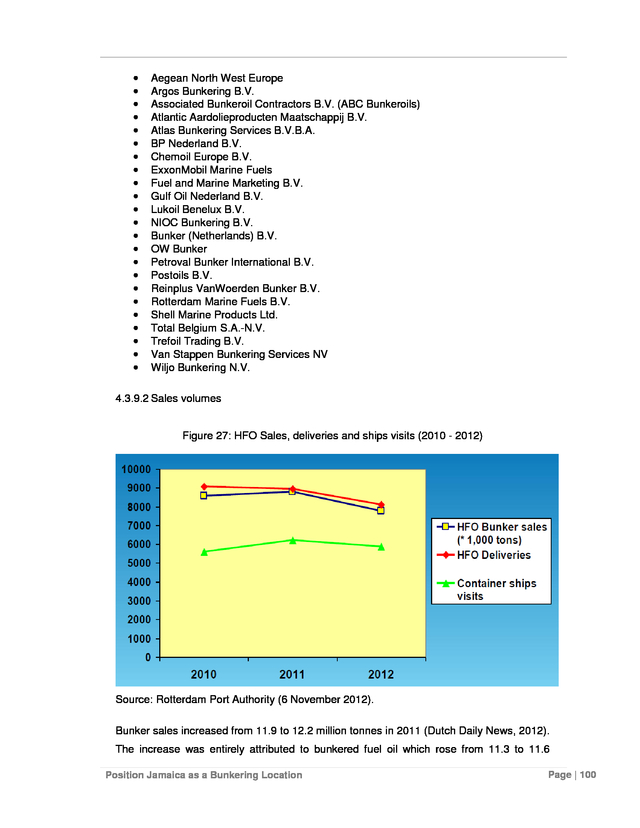

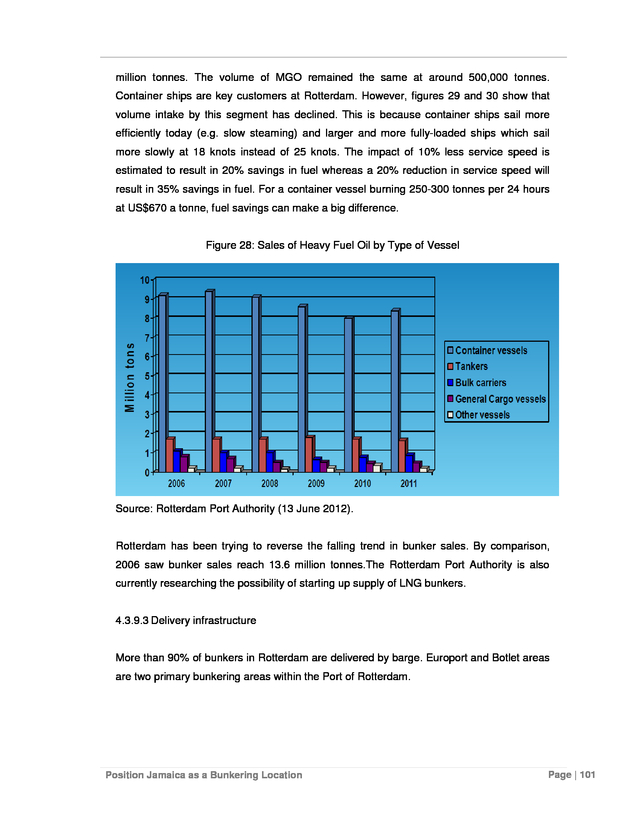

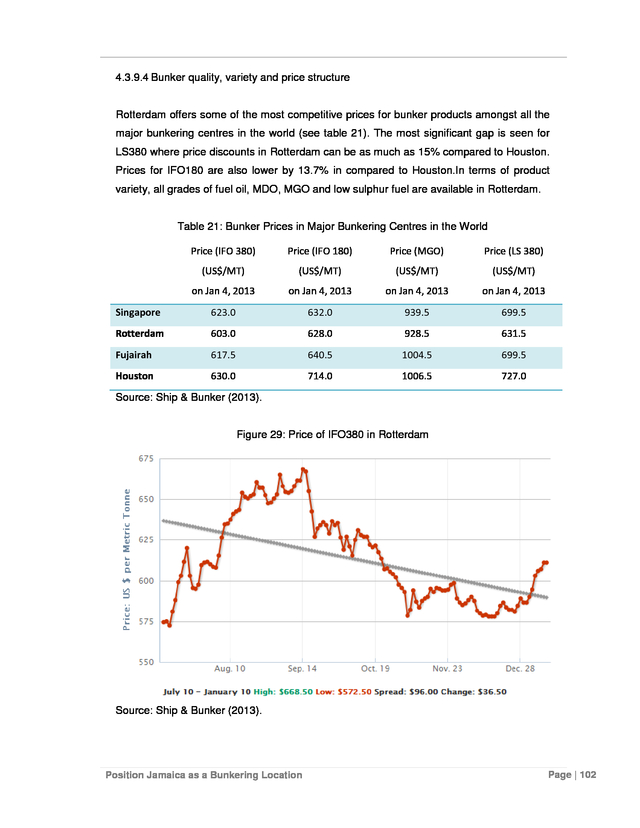

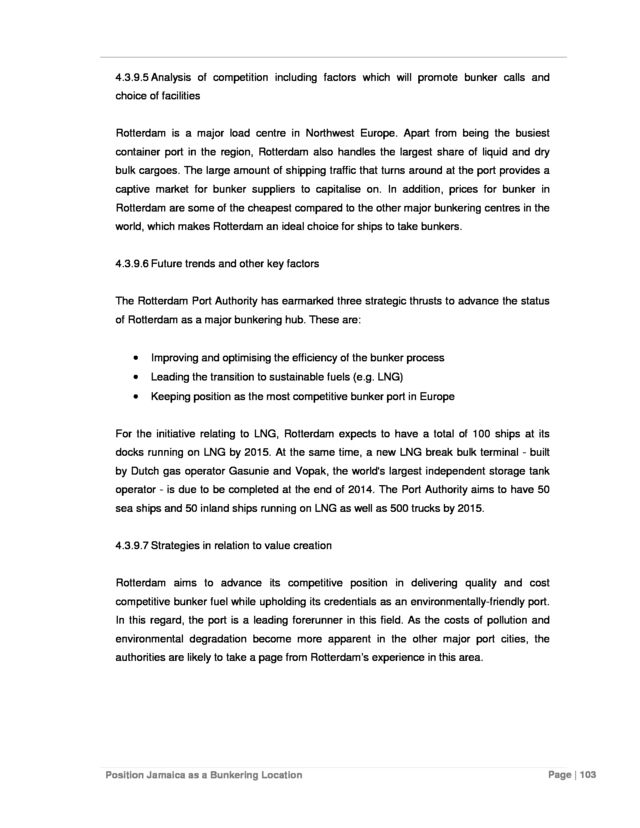

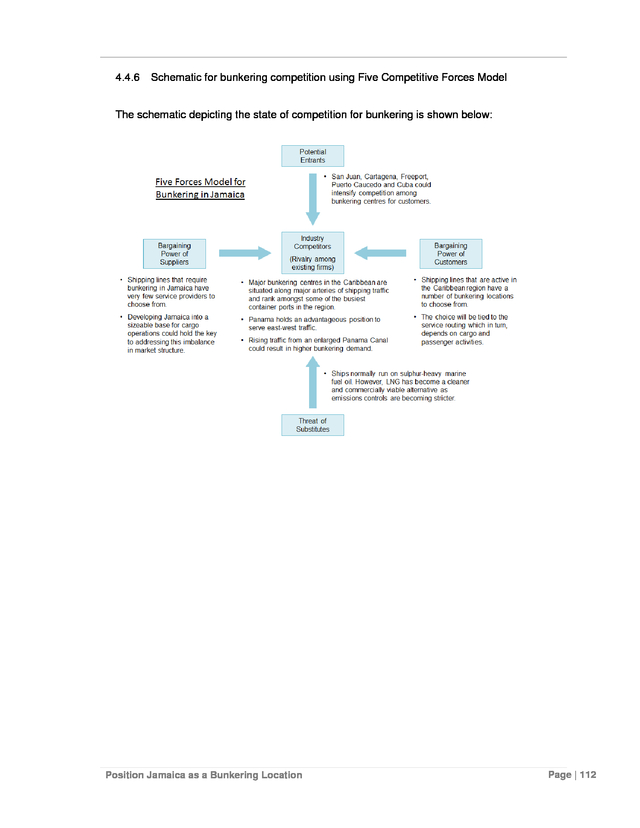

5) 4.3.9 Rotterdam 4.3.9.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.9.2 Sales volumes 4.3.9.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.9.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.9.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.9.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.9.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.3.10 Singapore 4.3.10.1 Bunker suppliers and service providers 4.3.10.2 Sales volumes 4.3.10.3 Delivery infrastructure 4.3.10.4 Bunker quality, variety and price structure 4.3.10.5 Analysis of competition including factors which will promote bunker calls and choice of facilities 4.3.10.6 Future trends and other key factors 4.3.10.7 Strategies in relation to value creation 4.4 Competitive dynamics 4.4.1 Current state of competition in the Caribbean 4.4.2 Threat of new competitor bunkering centres and players 4.4.3 Potential for substitutes 4.4.4 Bargaining power of shipping lines (customers) 4.4.5 Bargaining power of bunkering service providers 4.4.6 Schematic for bunkering competition using Five Competitive Forces Model 5. SWOT Analysis 5.1 Using strengths to take advantage of opportunities presented 5.2 Overcoming weaknesses that prevent taking advantage of opportunities 5.3 Using strengths to reduce the impact of threats 5.4 Overcoming weaknesses that will make these threats a reality 6. Environmental Impact Assessment, Regulatory Requirement and Quality Standards 6.1 Vision 2030 Jamaica – development and sustainability recognised as integrated pillars of success 6.2 Environmental impact and risks associated with bunkering activity 6.2.1 Marine environment 6.2.2 Air-borne environment 6.2.3 Land-based environment 6.2.4 Hazard risk management and response measures 6.3 Increased bunkering activity in Jamaica: gradual approach with active management of resources for long term sustainability 7. Recommendations and Policy Action Plans 7.1 Short term: 2 years 7.1.1 Establish central coordinating body for bunkering development Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location 96 96 97 98 99 100 100 100 101 101 101 102 103 104 104 106 106 106 107 107 108 108 109 110 111 112 112 113 114 114 117 117 122 124 126 128 129 129 129 Page | 4

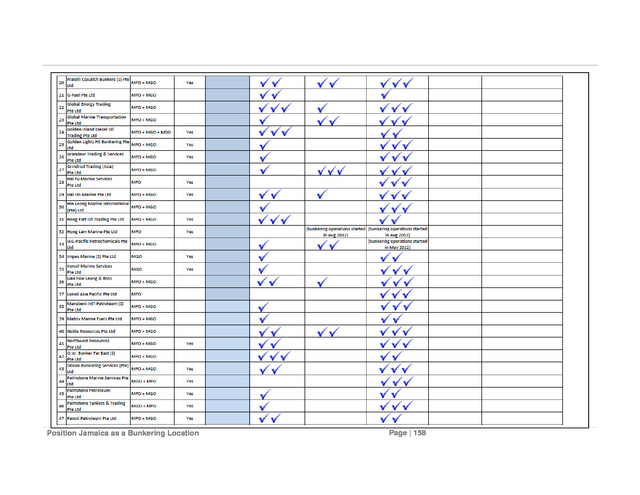

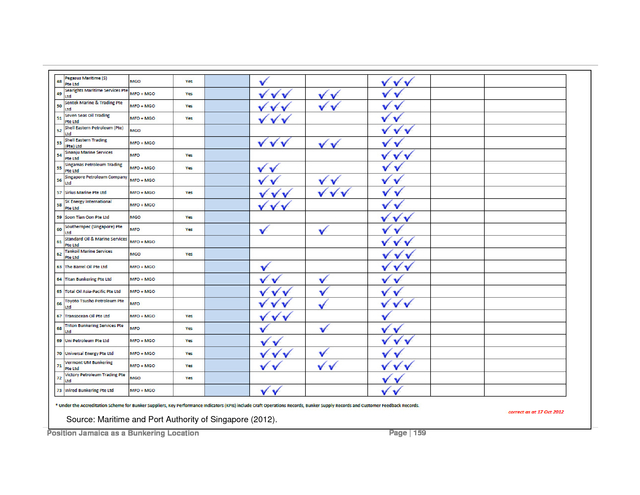

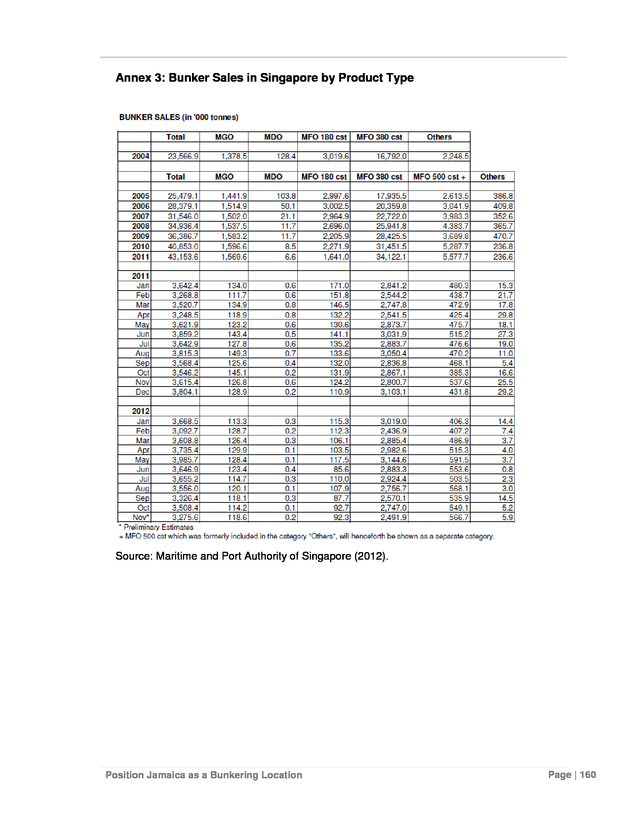

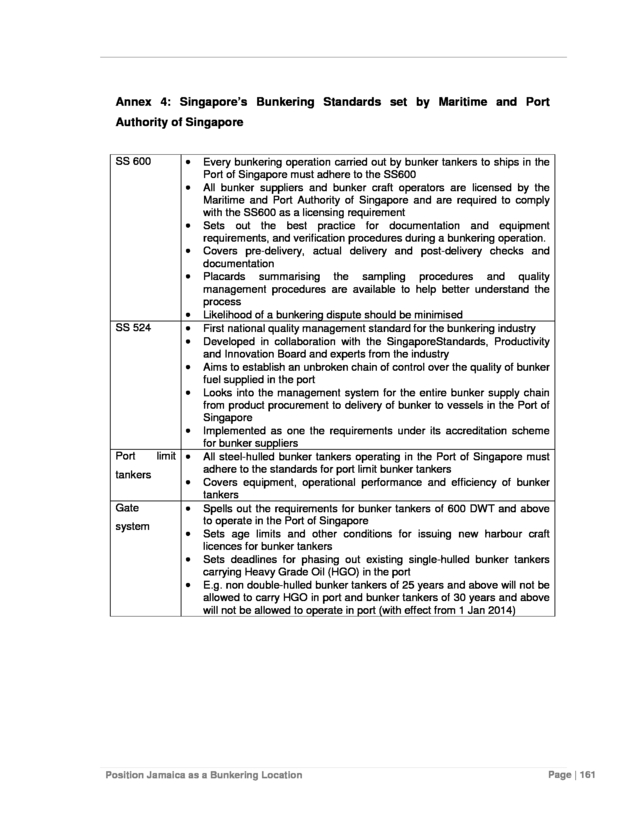

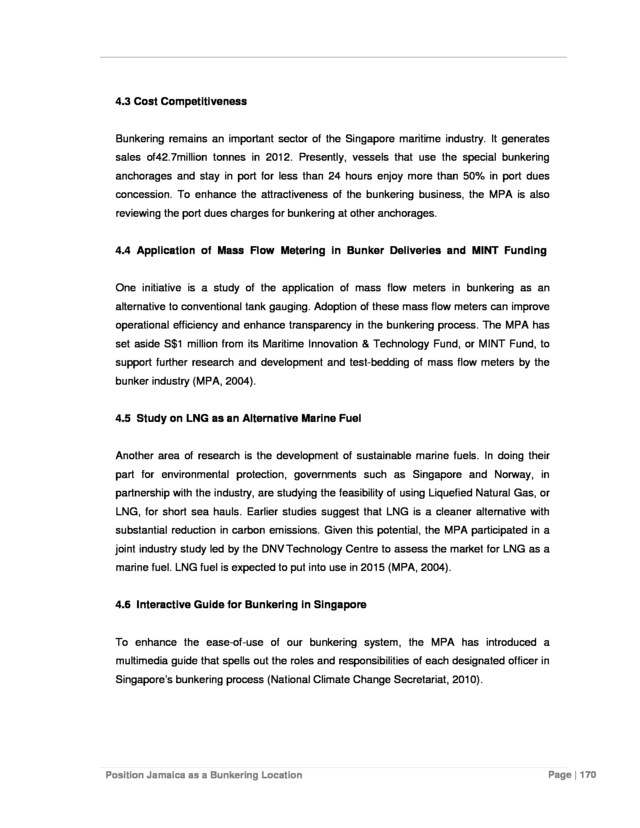

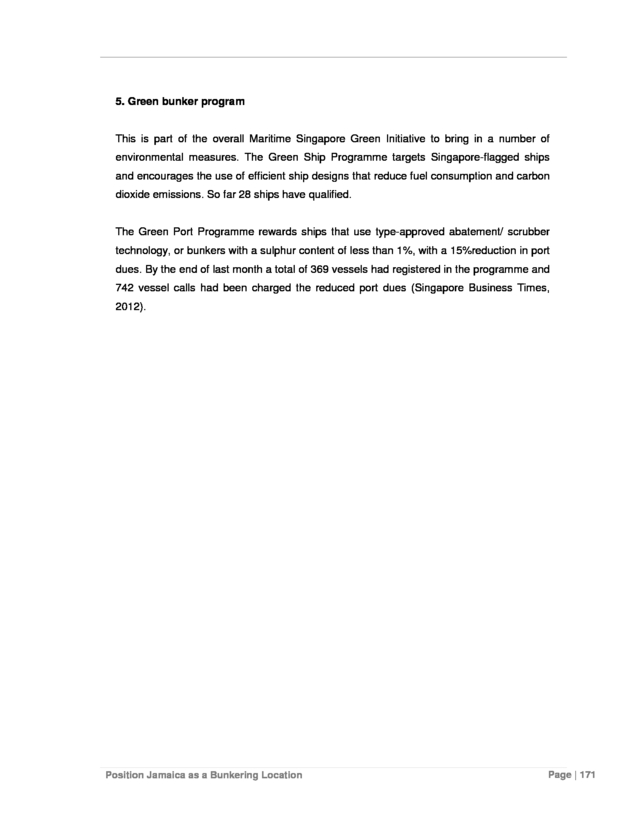

6) 7.1.2 7.1.3 Develop strong reputation and credibility for stringent bunkering standards Supply low sulphur fuel 130 134 7.1.4 Increasing capacity of fuel storage facilities 134 7.1.5Speed up dutyreclaim procedure and minimise bureaucracy 7.1.6 Develop petroleum free zones 7.1.7Develop competitive market structure 7.1.8 Connecting the bunkering community and publicity campaign 135 136 138 139 7.1.9 Human capital development for bunkering 7.2 Medium term: 5 years 7.2.1 Legislative framework for shipping, logistics and business at large 7.2.2 Global drive towards environmentally-friendly shipping 7.3 Medium to longer term: 5 to 10 years 7.3.1 Develop comprehensive suite of ship-related services Annex 1: Bunkering hub promotion policies in Panama Annex 2: Information on licensed bunker supplier in Port of Singapore Annex 3: Bunker sales in Singapore by product type Annex 4: Singapore’s Bunkering Standards set by MPA of Singapore Annex 5: Bunkering hub promotion policies in Singapore Annex 6: Joint Oil Spill Exercise 2012 list of participants Annex 7:Skill sets required for the development of Jamaica as a bunkering hub 139 140 140 141 142 142 143 152 155 156 157 166 167 Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 5

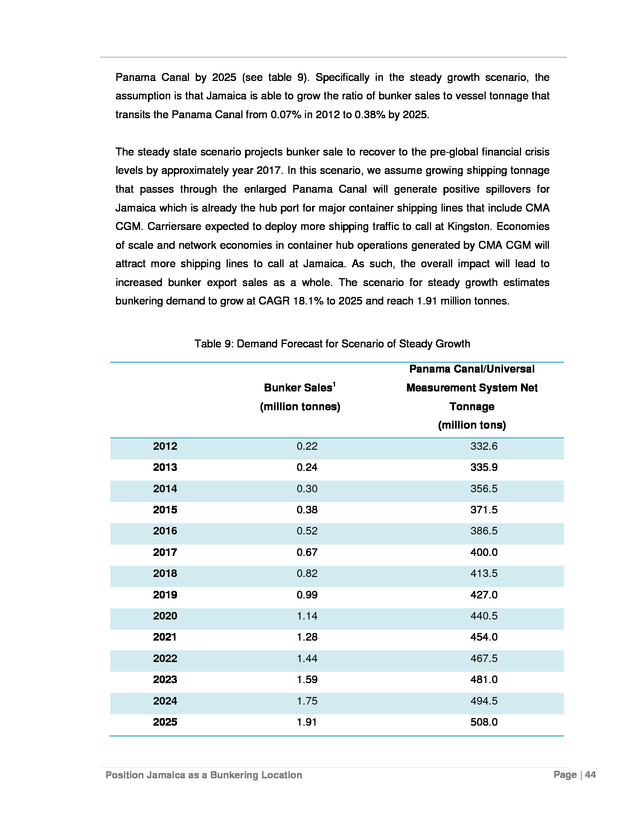

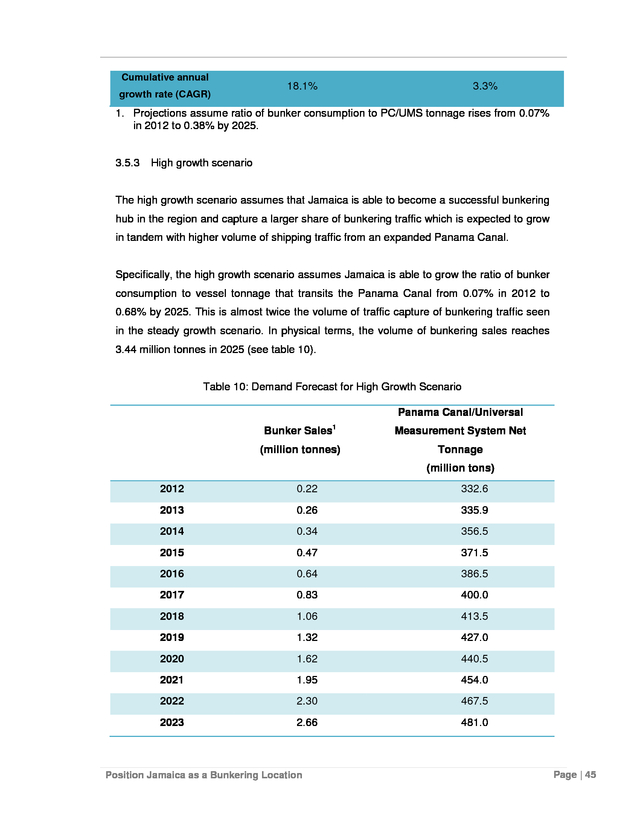

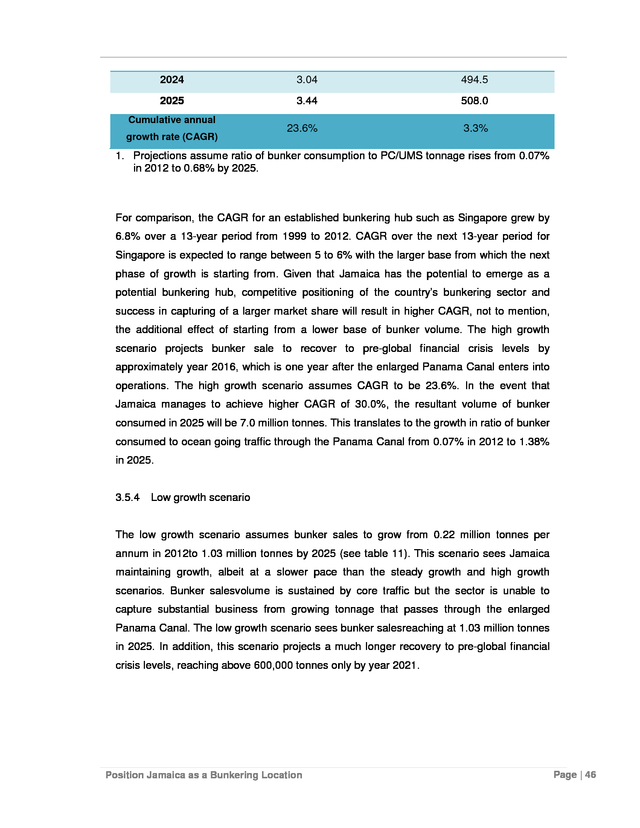

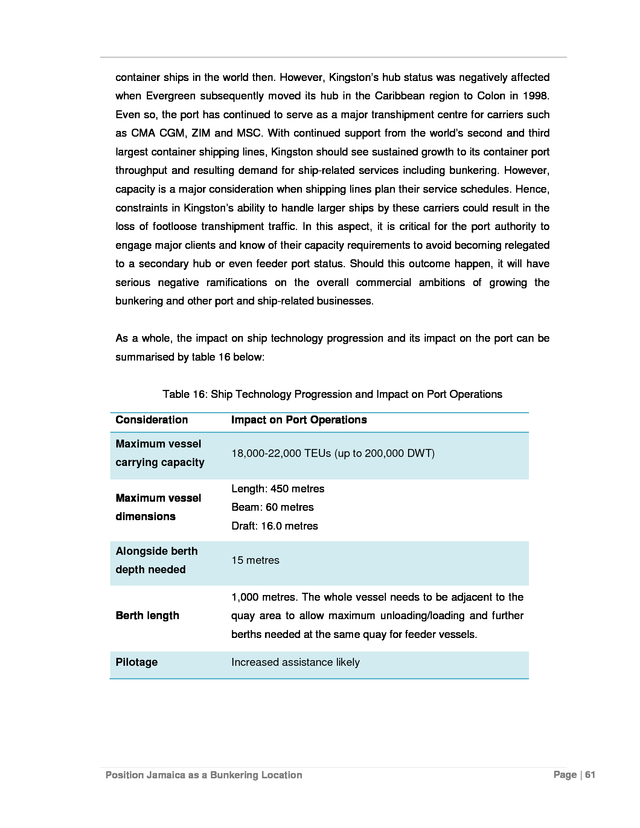

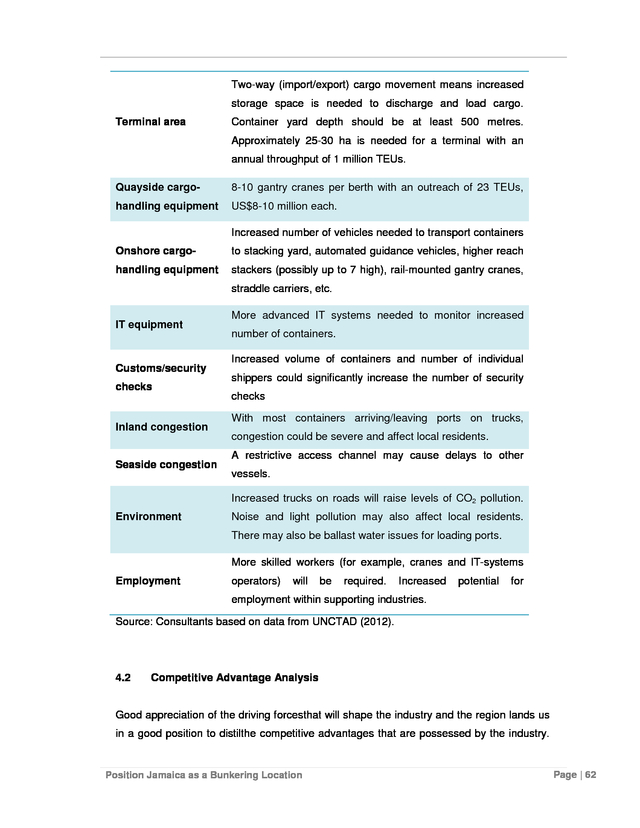

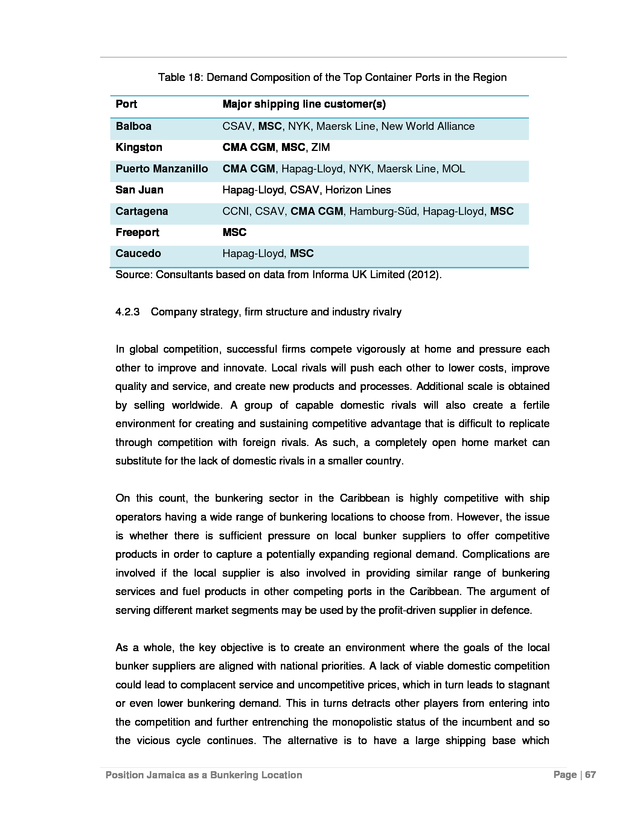

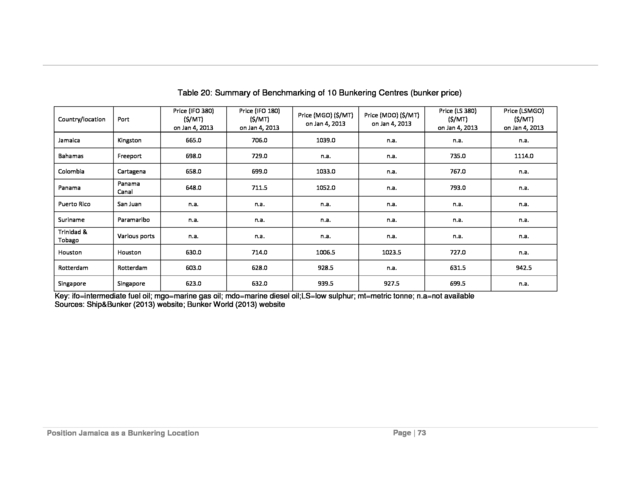

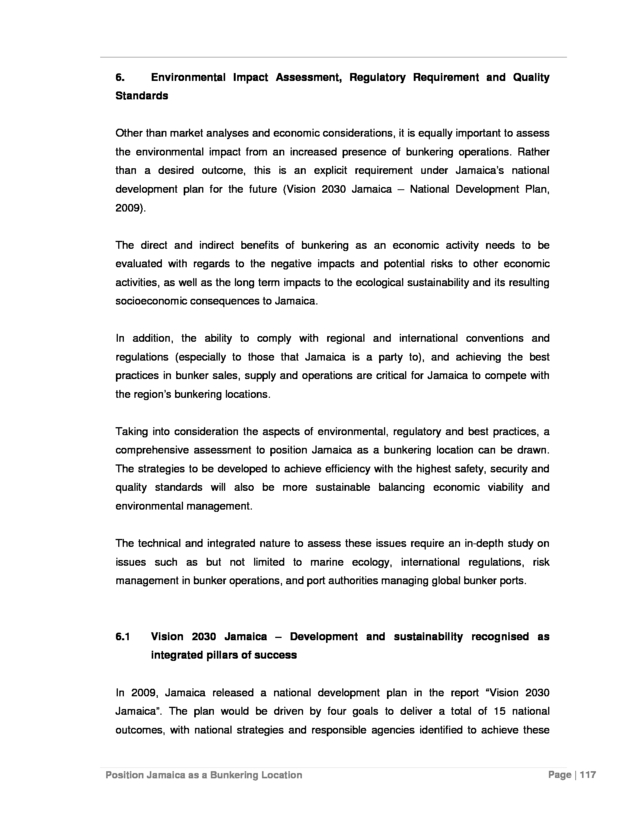

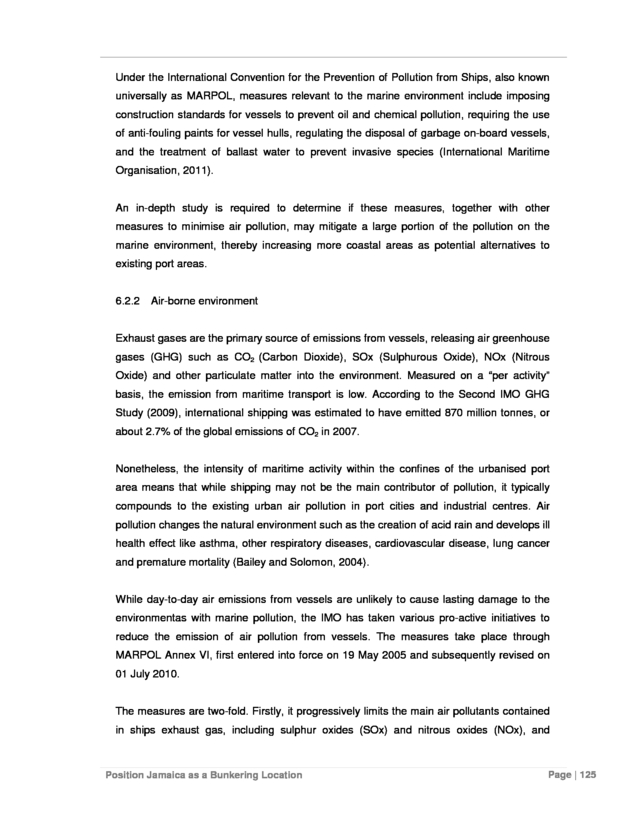

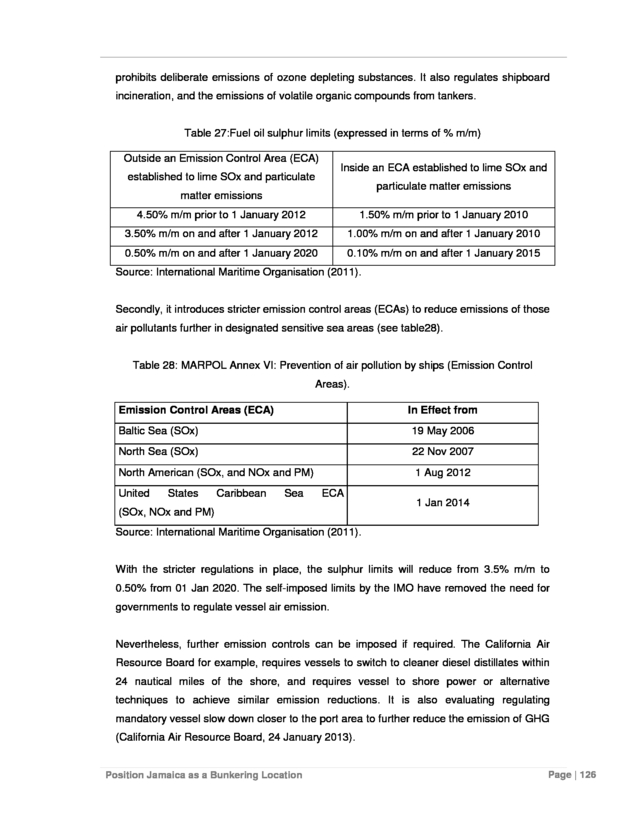

7) List of Tables Table 1: Bunker Export Sales in Jamaica (2005-2012) Table 2: Direct Economic Impact of the Bunkering Sector in Jamaica Table 3: Direct Economic Impact of the Bunkering Sector in Singapore Table 4: Bunker Prices of Kingston and Major Bunkering Centres Table 5: Comparison of Bunker Prices (4 January 2013, US$ per metric tonne) Table 6: GDP per Tonne of Bunker Consumed/Sold Table 7: Direct and Indirect Economic Impact of the Bunkering Sector(in US$’000) Table 8: Induced Economic Impact of Bunkering in Jamaica Table 9: Demand Forecast for Scenario of Steady State Growth Table 10: Demand Forecast for High Growth Scenario Table 11: Demand Forecast for Low Growth Scenario Table 12: Summary of Demand Forecasts Table 13: Real GDP Growth Rate in the Caribbean Region and US (2009-2013) Table 14: Cruise Lines and Their Market Shares of World Wide Passengers (2012) Table 15: Size of Largest Container Vessel Deployed (1988-2012) Table 16: Ship Technology Progression and Impact on Port Operations Table 17: Quality of Port Infrastructure Table 18: Demand Composition of the Top Container Ports in the Region Table 19: Summary of Benchmarking of 10 Bunkering Centres (suppliers, sales, infrastructure and fuel grades available) Table 20: Summary of Benchmarking of 10 Bunkering Centres (bunker price) Table 21: Bunker Prices in Major Bunkering Centres in the World Table 22: Port Dues Structure in Singapore for Bunker Tankers Table 23: Model for SWOT Analysis Applied to the Bunkering Industry in Jamaica Table 24: Enhanced SWOT Analysis Applied to the Bunkering Industry in Jamaica Table 25: Long-term National Strategies that Affect the Decision to Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location for the Caribbean Region Table 26: Estimation of Associated Shipping Traffic for 500,000 Metric Tons Bunker Operations in Panama Table 27: Fuel Oil Sulphur Limits (expressed in terms of % m/m) Table 28: MARPOL Annex VI: Prevention of Air Pollution by Ships (Emission Control Areas) Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page 20 21 22 23 23 24 25 27 42 43 45 46 49 54 55 58 61 64 69 70 99 105 110 111 115 120 123 123 Page | 6

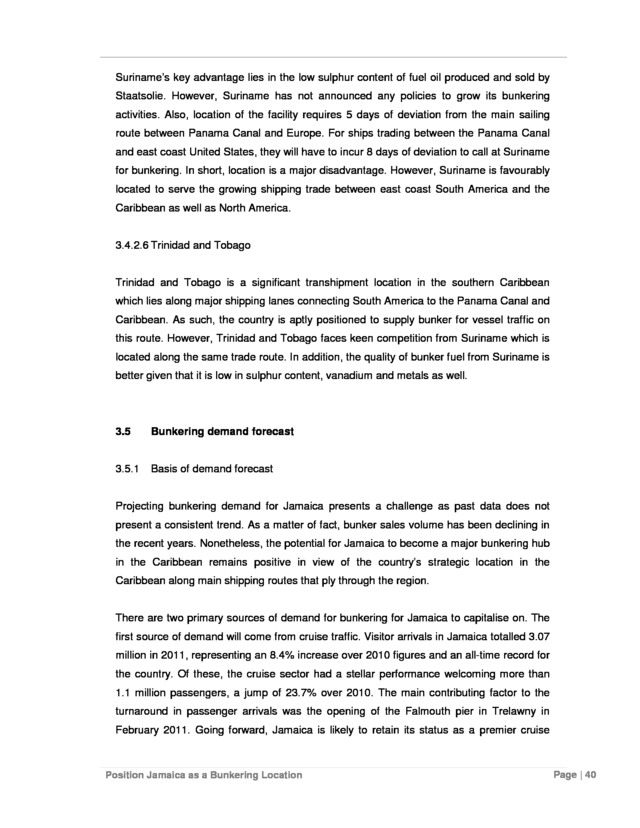

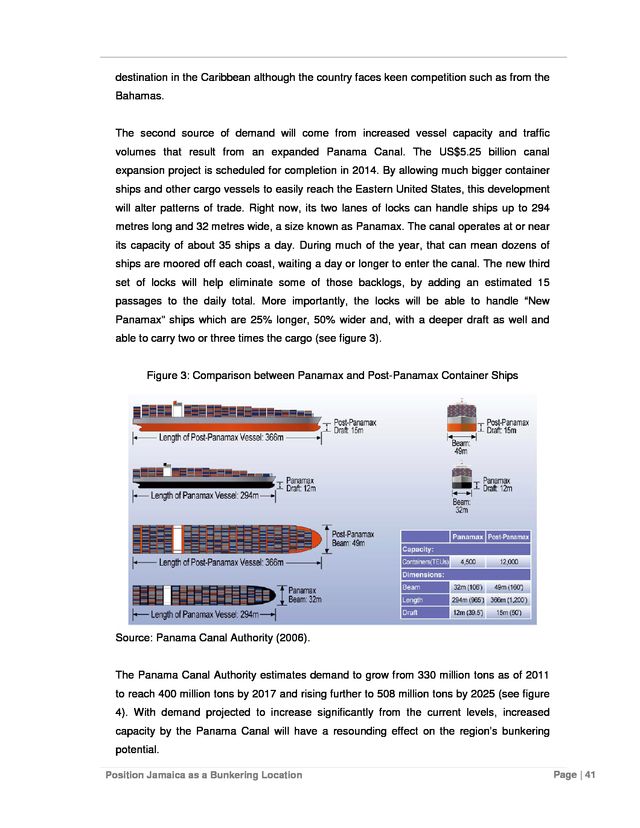

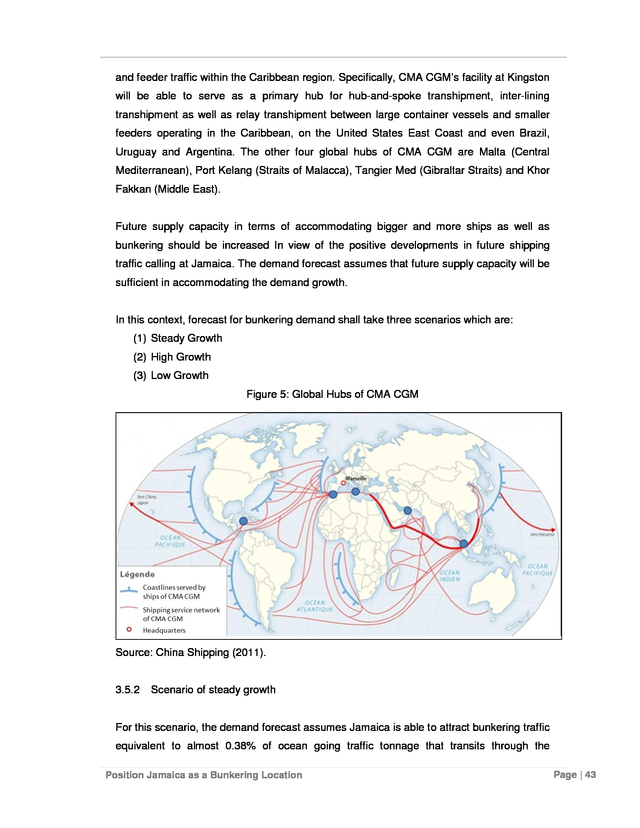

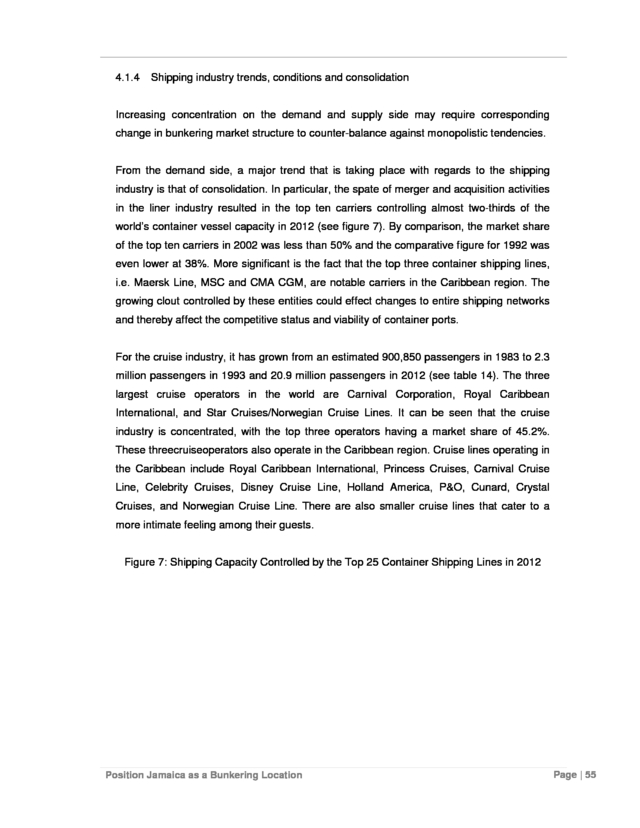

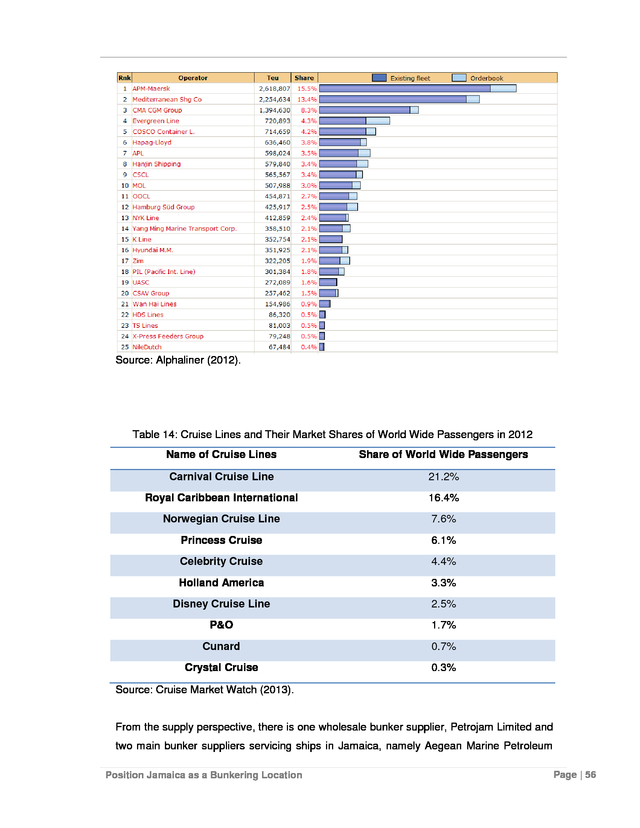

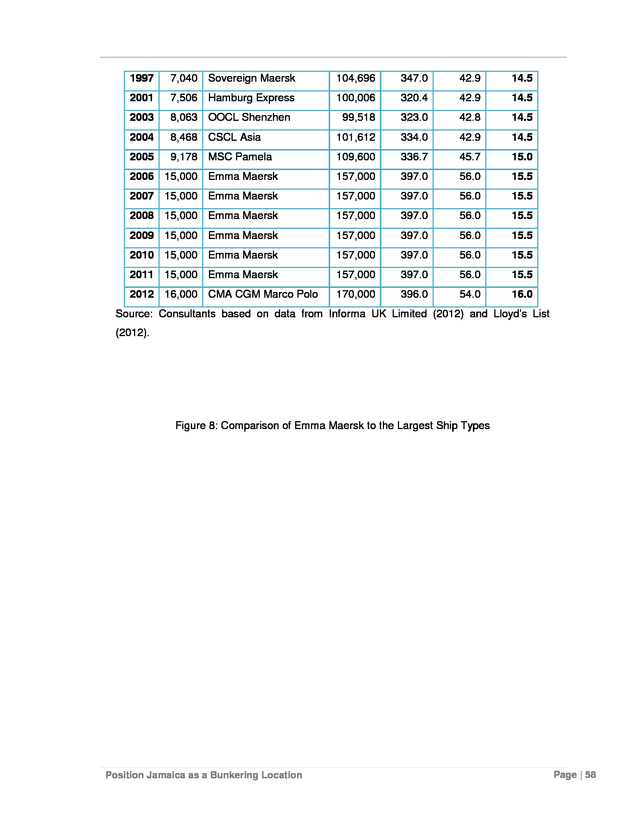

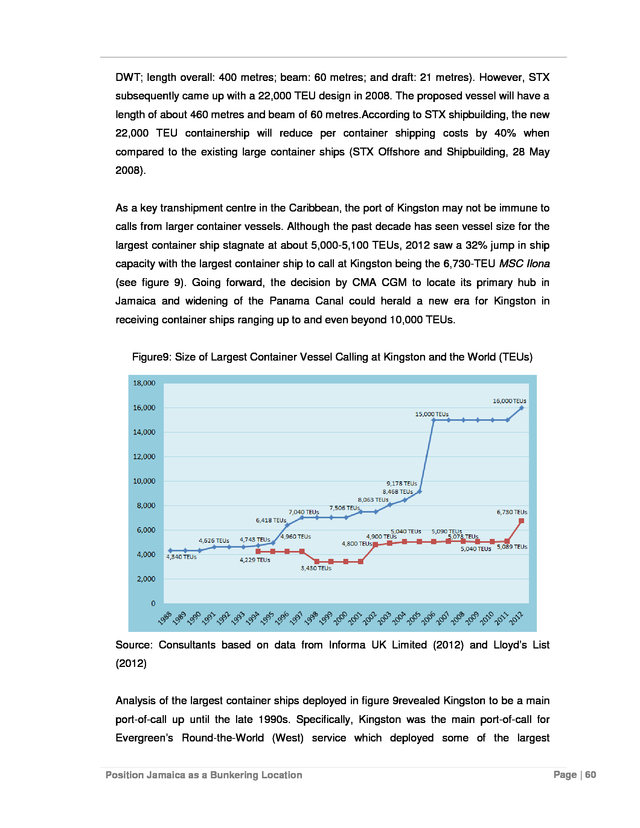

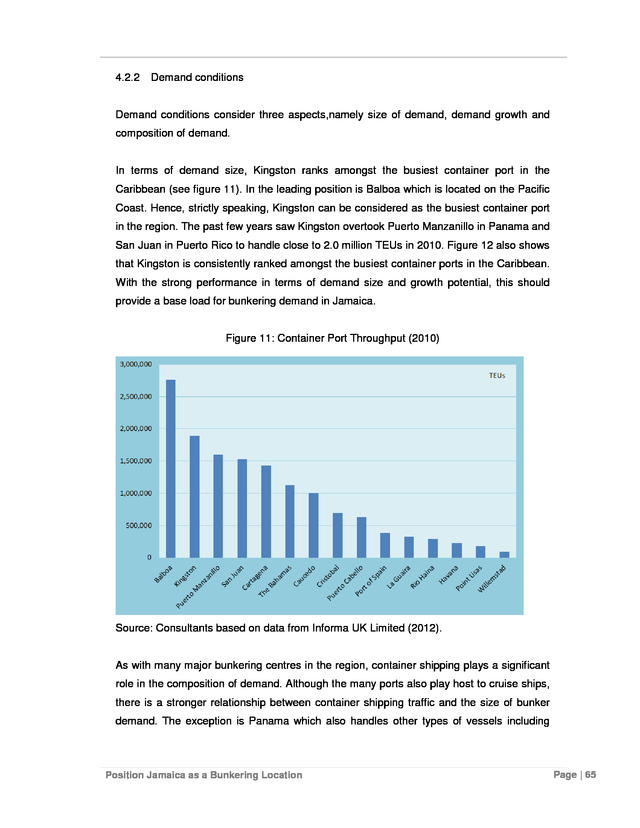

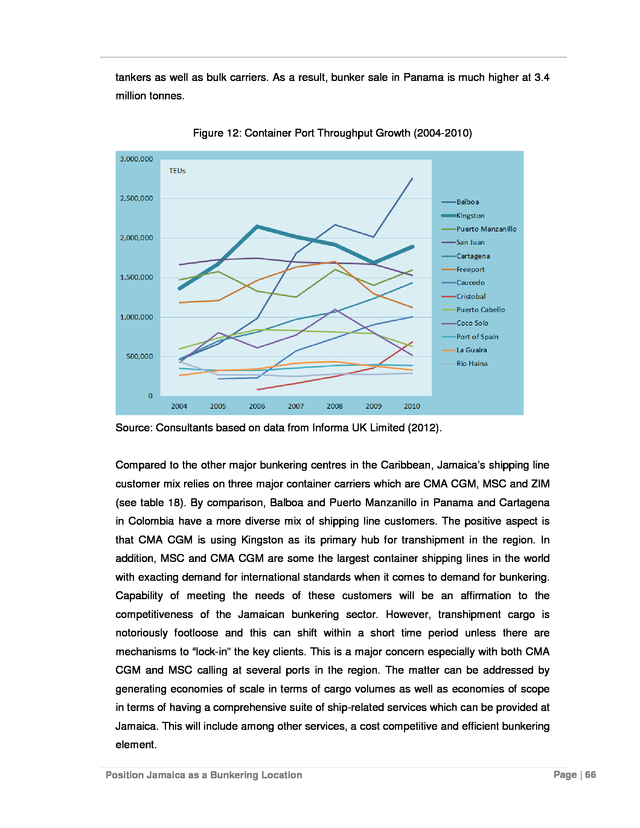

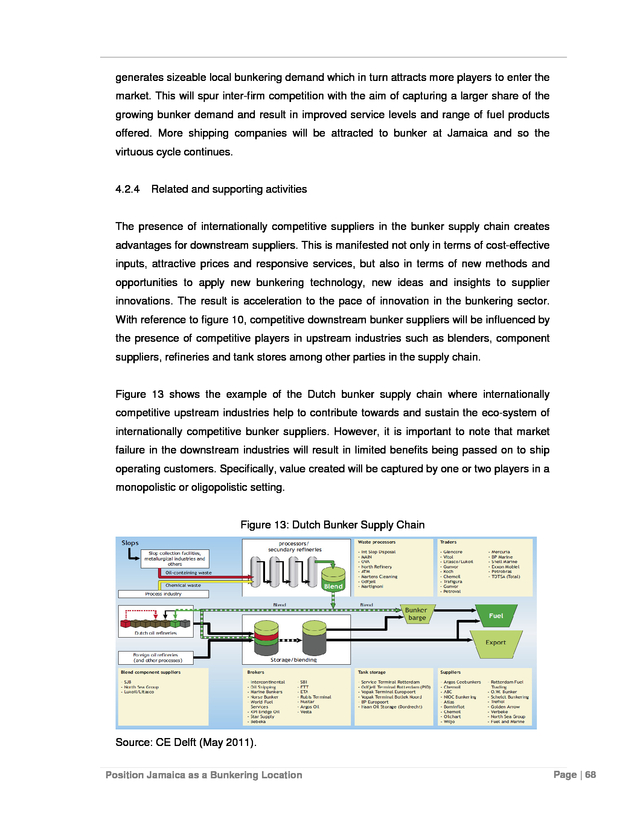

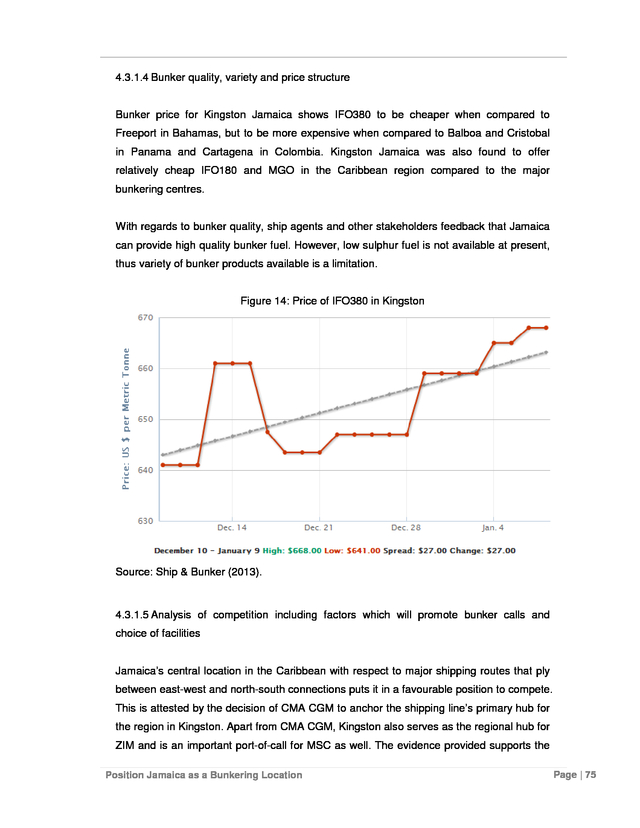

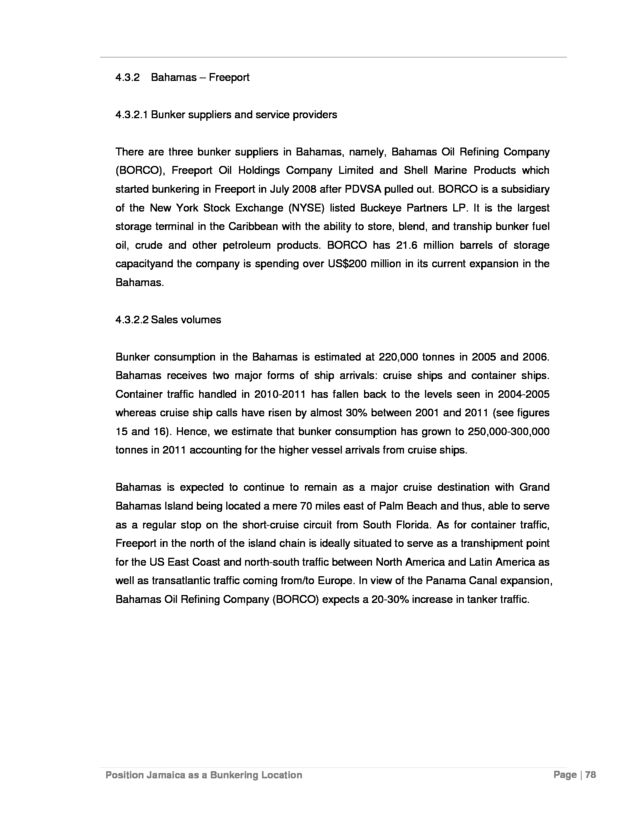

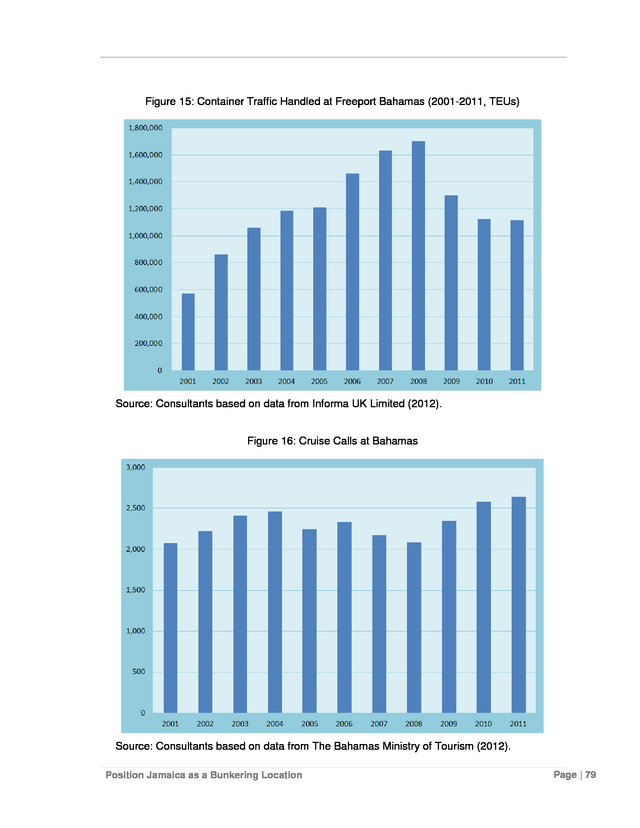

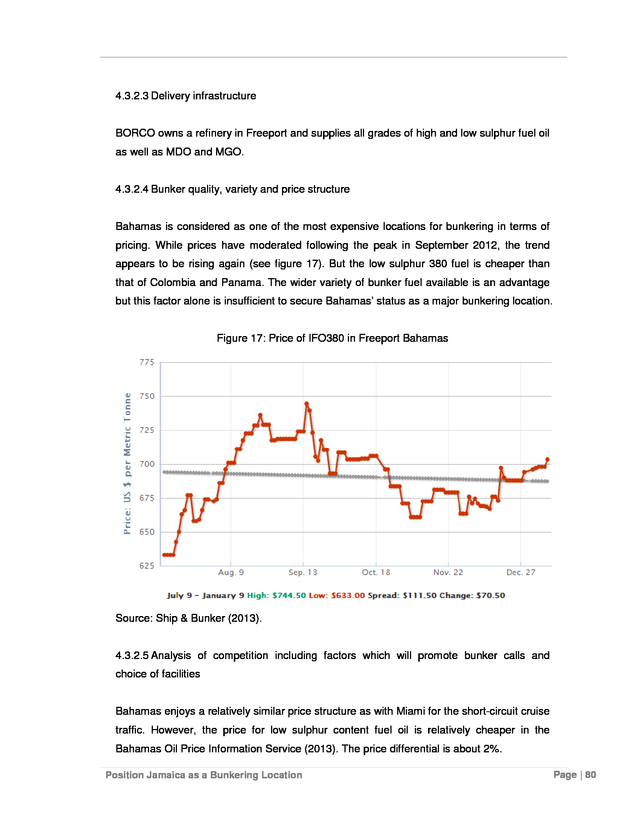

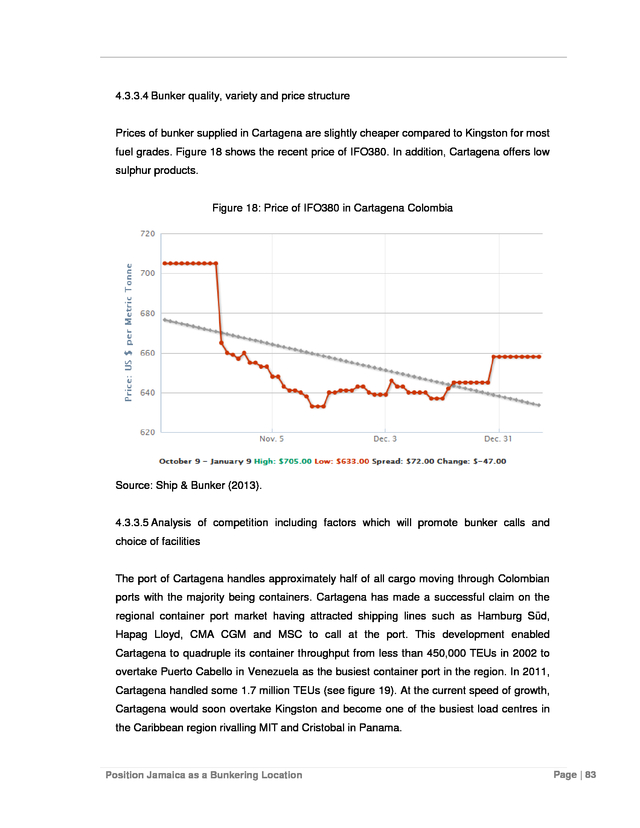

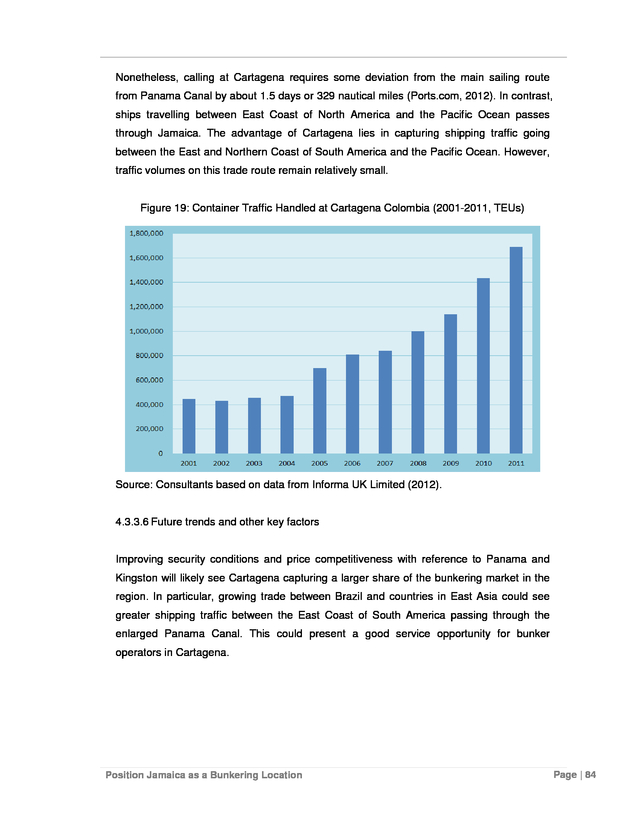

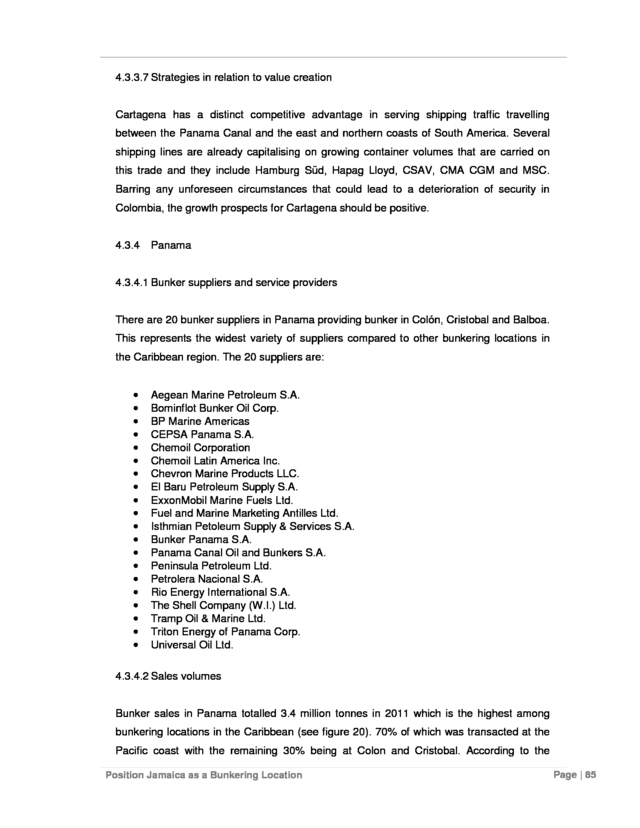

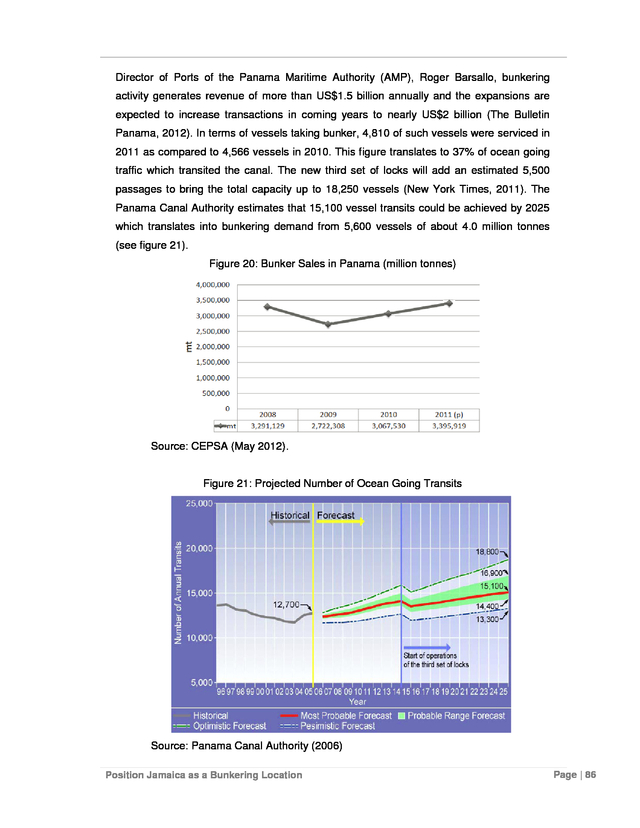

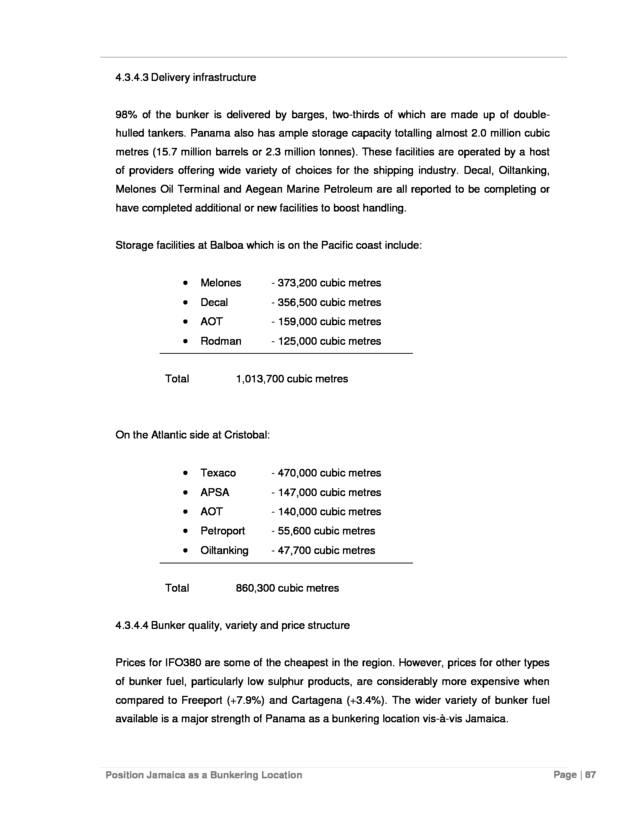

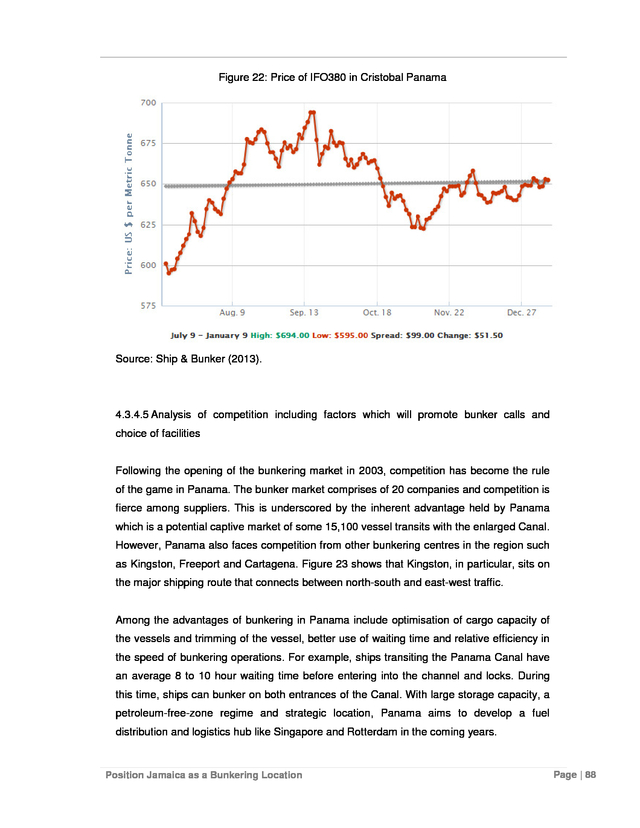

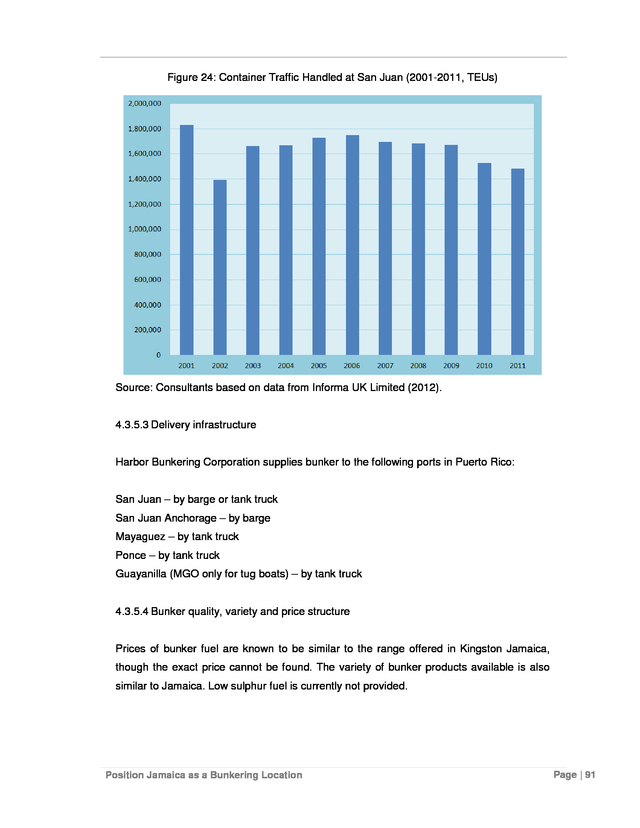

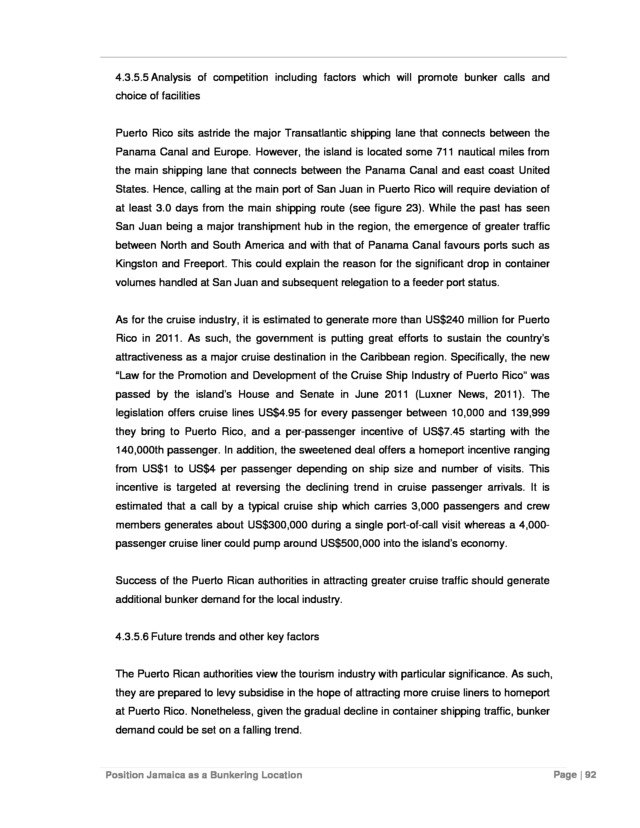

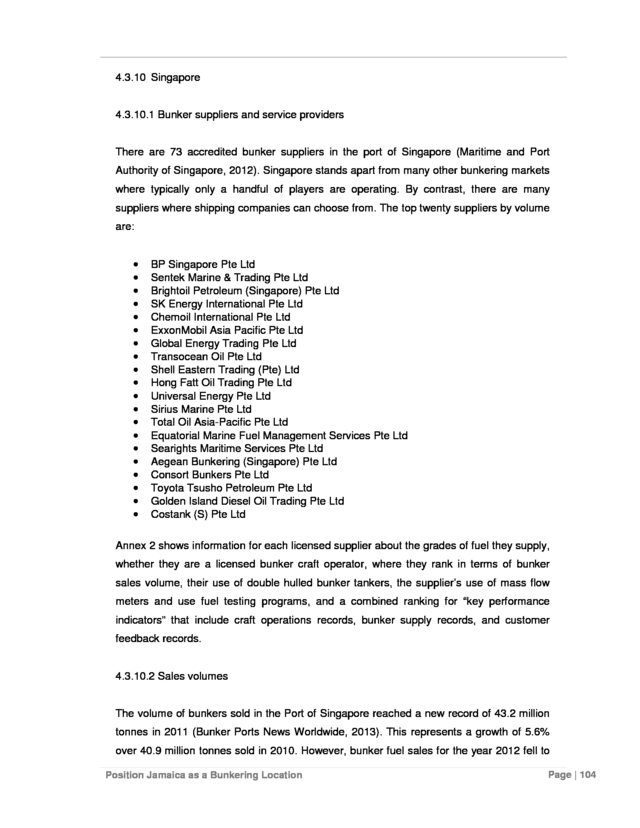

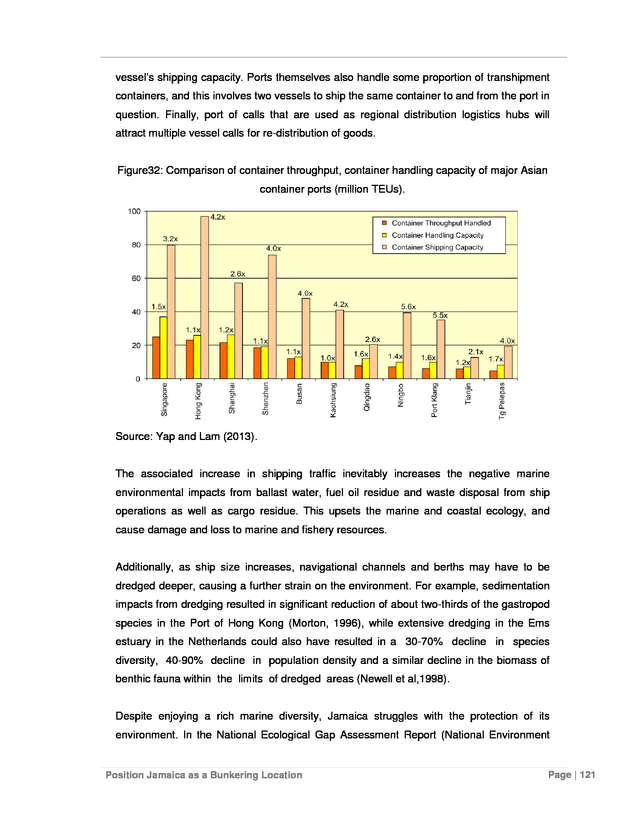

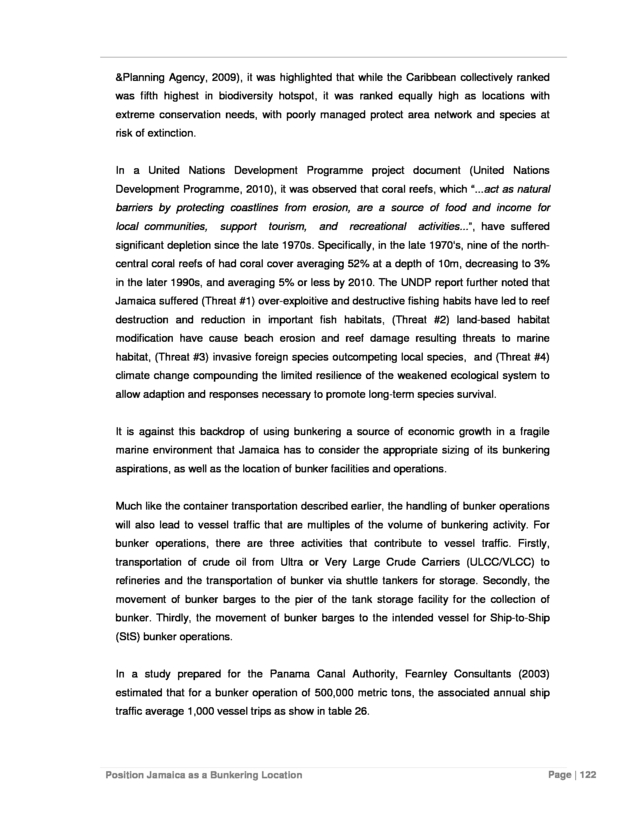

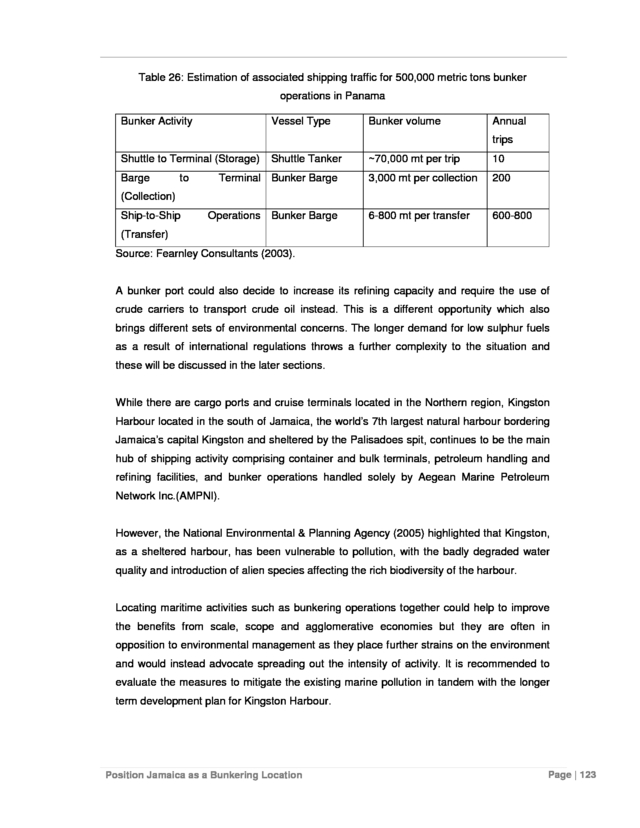

8) List of Figures Figure 1: Economic Linkages of Bunkering with Wider Economy Figure 2: Container Throughput Performance (2005-2010; Market Share %) Figure 3: Comparison between Panamax and Post-Panamax Container Ships Figure 4: Panama Canal Expansion and Projected Demand to 2025 Figure 5: Global Hubs of CMA CGM Figure 6: Summary of Demand Forecasts (in million tonnes) Figure 7: Shipping Capacity Controlled by the Top 25 Container Shipping Lines Figure 8: Comparison of Emma Maersk to the Largest Ship Types Figure 9: Size of Largest Container Vessel Calling at Kingston and the World Figure 10: The Bunker Supply Chain Figure 11: Container Port Throughput (2010) Figure 12: Container Port Throughput Growth (2004-2010) Figure 13: Dutch Bunker Supply Chain Figure 14: Price of IFO380 in Kingston Figure 15: Container Traffic Handled at Freeport Bahamas (2001-2011, TEUs) Figure 16: Cruise Calls at Bahamas Figure 17: Price of IFO380 in Freeport Bahamas Figure 18: Price of IFO380 in Cartagena Colombia Figure 19: Container Traffic Handled at Cartagena Colombia (2001-2011, TEUs) Figure 20: Bunker Sales in Panama (million tonnes) Figure 21: Projected Number of Ocean Going Transits Figure 22: Price of IFO380 in Cristobal Panama Figure 23: Shipping Traffic and Major Container Ports in the Caribbean Figure 24: Container Traffic Handled at San Juan (2001-2011, TEUs) Figure 25: Refinery Production by Staatsolie Maatschappij Suriname NV Figure 26: Price of IFO380 in Houston Figure 27: HFO Sales, deliveries and ships visits (2010 - 2012) Figure 28: Sales of Heavy Fuel Oil by Type of Vessel Figure 29: Price of IFO380 in Rotterdam Figure 30: Volume of Bunker Sales in Singapore (see annex 2 for details) Figure 31: Price of IFO380 in Singapore Figure 32: Comparison of Container Throughput, Container Handling Capacity of Major Asian Container Ports in 2006 (million TEUs) Figure 33: Proposed National Protected Areas on Jamaica – Priority Ranking by Biodiversity Figure 34: LNG Bunkering Demand, 2012 and 2020 Figure 35: LNG Bunkering Locations, 2012 and 2020 Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page 26 32 39 40 41 47 53 56 57 60 62 63 65 72 76 76 77 80 81 83 83 85 86 88 91 96 97 98 99 102 103 118 121 125 126 Page | 7

9) List of Abbreviations and Acronyms AMP AMPNI AS BIMCO BORCO BS CAGR CCNR CEPSA CO2 CSAV CST CUPET DMA DNV DWT ECA ECLAC EMSA FCCA FOCOL GDP GHG HBC HFO HGO IFO IMO IT JAMPRO JSR LNG ISO LOA LS MAJ MARPOL MDO MFO Panama Maritime Authority Aegean Marine Petroleum Network Inc. Australia Standards Baltic and International Maritime Council Bahamas Oil Refining Company British Standards Cumulative Annual Growth Rate Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine Compañía Española de Petróleos, S.A. Carbon Dioxide Compañía Sud Americana de Vapores Centistoke Cuba Petroleum A type of marine distillate fuel as defined by ISO 8217 Fuel Standard Det Norske Veritas Deadweight Ton Emission Control Area Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean European Maritime Safety Agency Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association Freeport Oil Company Gross Domestic Product Green House Gases Harbor Bunkering Corporation Heavy Fuel Oil Heavy Grade Oil Intermediate Fuel Oil International Maritime Organisation Information Technology Jamaica Promotions Corporation Jamaica Ship Registry Liquefied Natural Gas International Standards Organisation Length Overall Low Sulphur Maritime Authority of Jamaica Marine Pollution Marine Diesel Oil Marine Fuel Oil Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 8

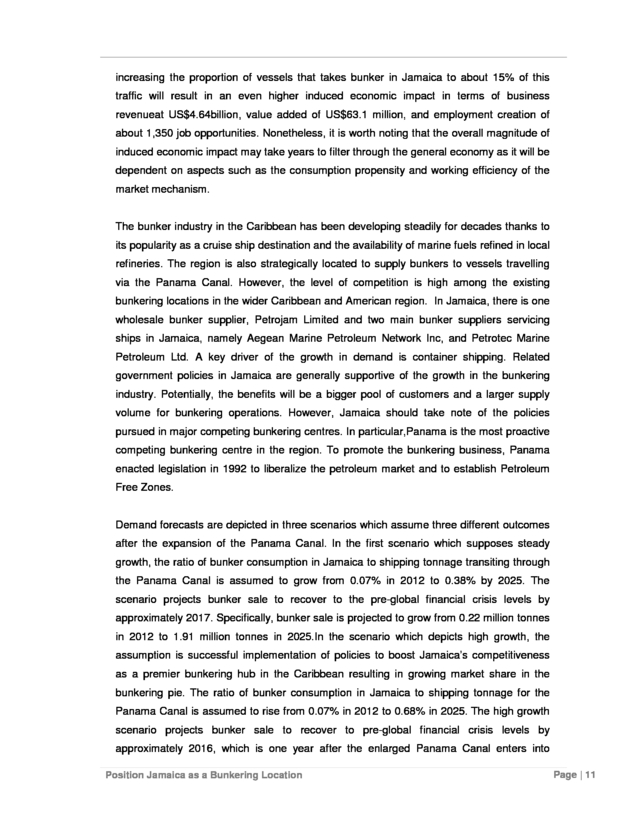

10) MGO MPA MSC MT N.A. NEPA NOx NYSE OCIMF OPEC P&I PAJ PCJ PC/UMS PDVSA PM R&D RMG SBA SIBCON SOx SS STS SWOT TEU UK ULCC UNCTAD UNDP US VLCC Marine Gas Oil Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore Mediterranean Shipping Company Metric Tonne Not Available National Environmental and Planning Agency Nitrous Oxide New York Stock Exchange Oil Companies International Marine Forum Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Protection and Indemnity Port Authority of Jamaica Petroleum Corporation of Jamaica Panama Canal Universal Measurement System Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. Particulate Matter Research and Development A type of marine residual fuel as defined by ISO 8217 Fuel Standard Special Bunkering Anchorages Singapore International Bunkering and Exhibition Conference Sulphurous Oxide Singapore Standards Ship-To-Ship Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit United Kingdom Ultra Large Crude Carrier United Nations Conference on Trade And Development United Nations Development Programme United States of America Very Large Crude Carrier Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 9

11) Executive Summary In October 2012, the Commonwealth Secretariat appointed Nanyang Technological University (Singapore) as consultants to undertake a study to position Jamaica as a bunkering location in the Caribbean Region.The team of consultants are Dr. LAM Siu Lee Jasmine (team leader and principal investigator), Dr. YAP Wei Yim (key investigator) and Mr. LEONG Meng Keong Edwin. Economic Impact Analysis and Market Assessment The study recognises that bunkering activities do not operate in isolation but form an important eco-system within the entire maritime cluster. The direct economic impact is estimated for total business revenue generated by bunkering activities at US$209.1 million which puts bunker sales at 1.44% of Jamaica’s GDP. In terms of direct value added contribution to GDP, bunkering activities are estimated to contribute US$2.7 million or 0.02% of the country’s GDP in 2011. As foremployment in terms of direct economic impact, the current bunkering sector is estimated to employ about 30 people based on the assumption of productivity employee at 10,000-15,000 metric tonne sales per annum. Considering both direct and indirect economic impact which are generated by shippingrelated activities will raise the estimates for business revenue generated to US$343.7 million or 2.37% of Jamaica’s GDP. Total value added contribution to GDP will similarly be higher at US$4.67 million or 0.03% of GDP. As for employment, the sales volume registered for 2011 and assumed productivity indicators suggest that employment attributable to the bunkering sector at about 100 people. Currently, the number of vessels that takes bunker in Jamaica is equivalent to about 5% of the ocean-going traffic that goes through the Panama Canal. The corresponding induced impact being business revenue of US$516 million, value added of US$7.0 million, and employment of about 150 jobsin one year. This assumes a consumption multiplier for the bunkering industry at 1.50. Increasing the number of vessels that takes bunker in Jamaica to about 10% of ocean-going traffic that goes through the Panama Canal will result in induced economic impact in terms of business revenueat US$3.1billion, value added of US$42.06 million, and employment creation of about 900 job opportunities. Success in Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 10

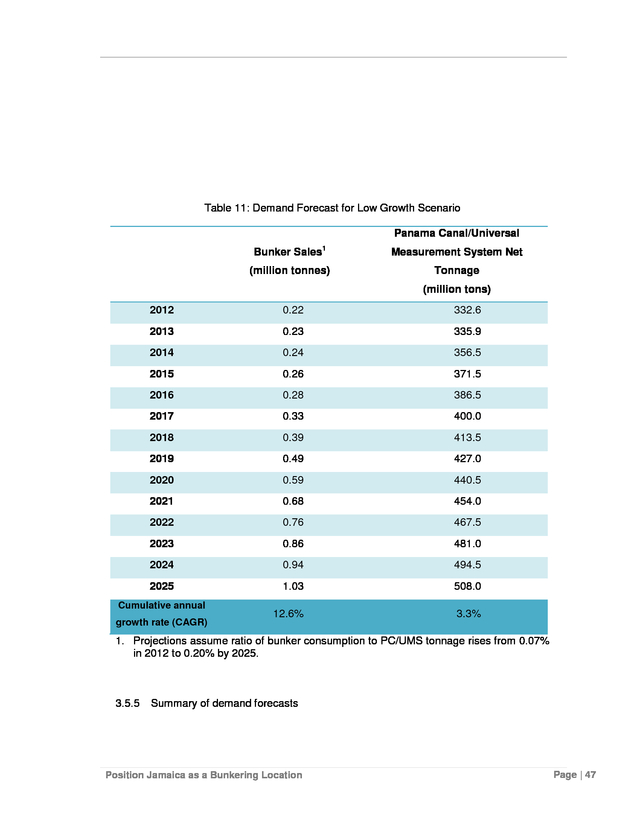

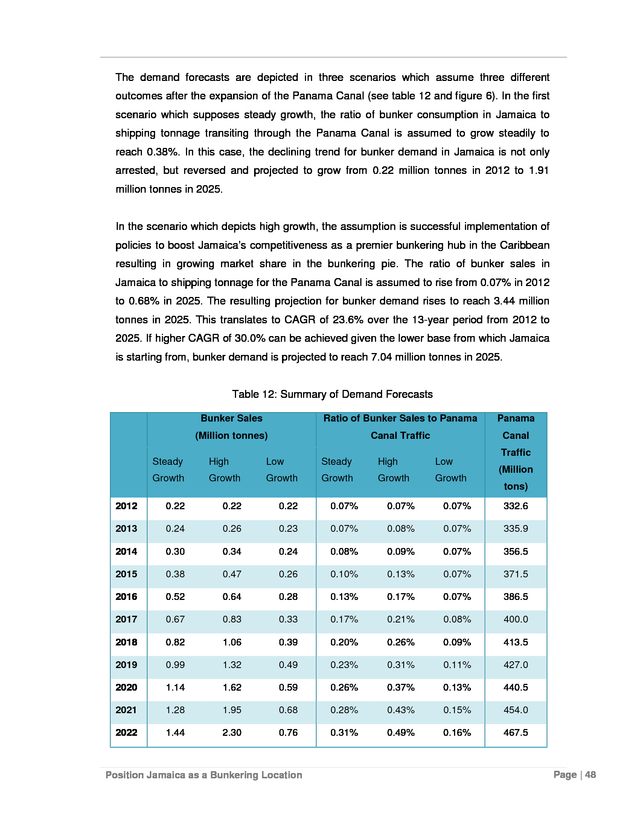

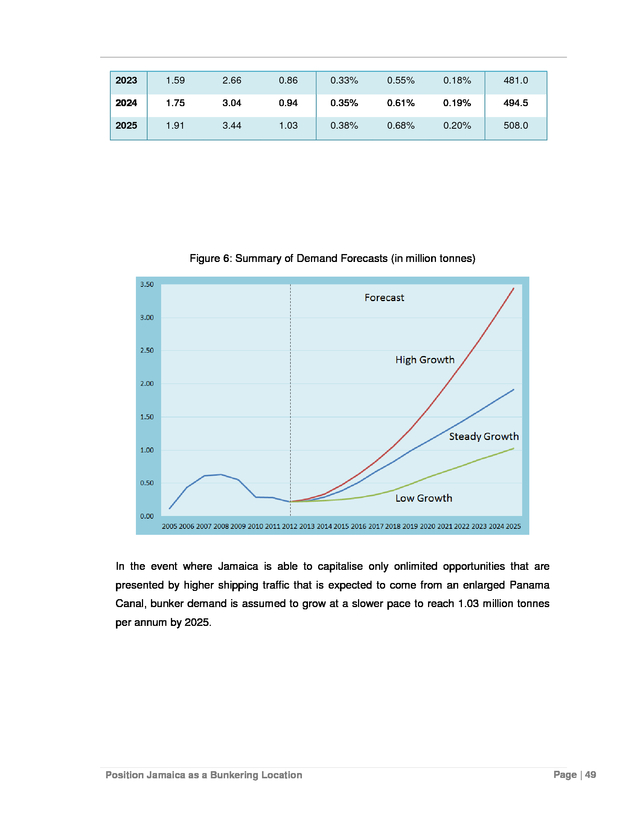

12) increasing the proportion of vessels that takes bunker in Jamaica to about 15% of this traffic will result in an even higher induced economic impact in terms of business revenueat US$4.64billion, value added of US$63.1 million, and employment creation of about 1,350 job opportunities. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the overall magnitude of induced economic impact may take years to filter through the general economy as it will be dependent on aspects such as the consumption propensity and working efficiency of the market mechanism. The bunker industry in the Caribbean has been developing steadily for decades thanks to its popularity as a cruise ship destination and the availability of marine fuels refined in local refineries. The region is also strategically located to supply bunkers to vessels travelling via the Panama Canal. However, the level of competition is high among the existing bunkering locations in the wider Caribbean and American region. In Jamaica, there is one wholesale bunker supplier, Petrojam Limited and two main bunker suppliers servicing ships in Jamaica, namely Aegean Marine Petroleum Network Inc, and Petrotec Marine Petroleum Ltd. A key driver of the growth in demand is container shipping. Related government policies in Jamaica are generally supportive of the growth in the bunkering industry. Potentially, the benefits will be a bigger pool of customers and a larger supply volume for bunkering operations. However, Jamaica should take note of the policies pursued in major competing bunkering centres. In particular,Panama is the most proactive competing bunkering centre in the region. To promote the bunkering business, Panama enacted legislation in 1992 to liberalize the petroleum market and to establish Petroleum Free Zones. Demand forecasts are depicted in three scenarios which assume three different outcomes after the expansion of the Panama Canal. In the first scenario which supposes steady growth, the ratio of bunker consumption in Jamaica to shipping tonnage transiting through the Panama Canal is assumed to grow from 0.07% in 2012 to 0.38% by 2025. The scenario projects bunker sale to recover to the pre-global financial crisis levels by approximately 2017. Specifically, bunker sale is projected to grow from 0.22 million tonnes in 2012 to 1.91 million tonnes in 2025.In the scenario which depicts high growth, the assumption is successful implementation of policies to boost Jamaica’s competitiveness as a premier bunkering hub in the Caribbean resulting in growing market share in the bunkering pie. The ratio of bunker consumption in Jamaica to shipping tonnage for the Panama Canal is assumed to rise from 0.07% in 2012 to 0.68% in 2025. The high growth scenario projects bunker sale to recover to pre-global financial crisis levels by approximately 2016, which is one year after the enlarged Panama Canal enters into Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 11

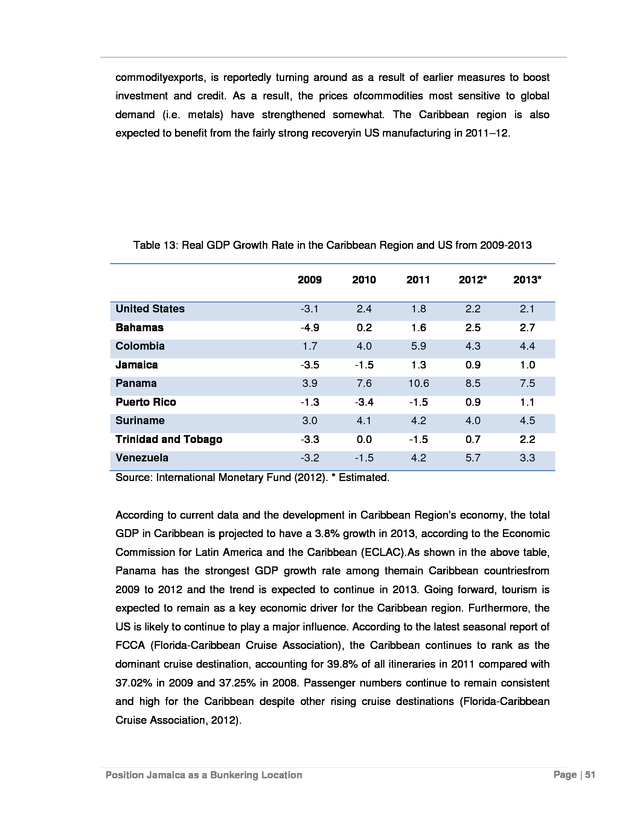

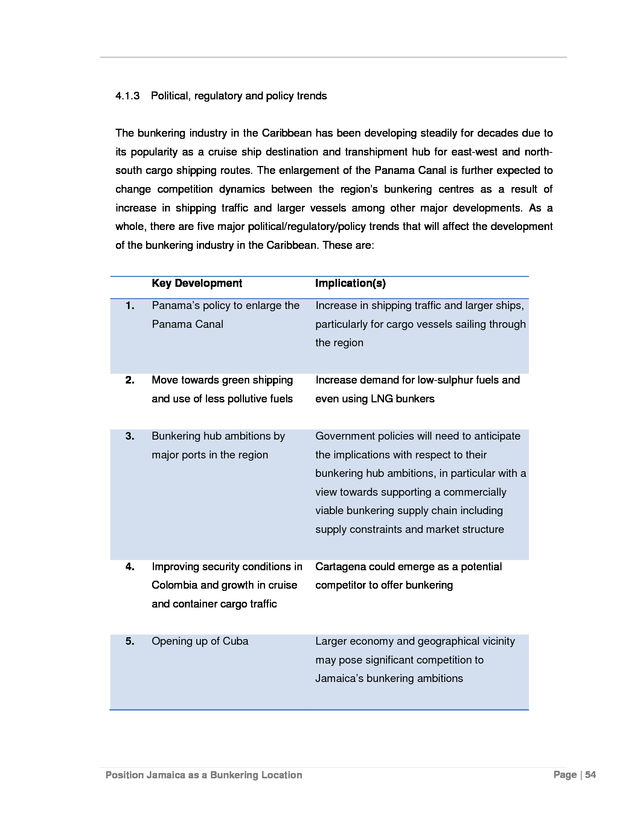

13) operations. By 2025, the projection for bunker demand is3.44 million tonnes. In the event where Jamaica is able to capitalise on limited growth opportunities, bunker demand is assumed to grow at a much slowerpace to reach 1.03 million tonnes per annum by 2025. In addition, this scenario projects a much longer recovery to pre-global financial crisis levels, reaching above 600,000 tonnes only by 2021. Environment Scan In terms of macroeconomic developments, the economic status in the Caribbean Region is largely driven by the global economy as well as developments in the US. Going forward, tourism is expected to remain as a key economic driver for the Caribbean region. Furthermore, the US is likely to continue to play a major influence. The bunkering industry in the Caribbean has been developing steadily for decades due to its popularity as a cruise ship destination and transhipment hub for east-west and northsouth cargo shipping routes. The enlargement of the Panama Canal is further expected to change competition dynamics between the region’s bunkering centres as a result of increase in shipping traffic and larger vessels. Other key political/regulatory/policy trends include the move towards green shipping and use of less pollutive fuels; bunkering hub ambitions by major ports in the region; improving security conditions in Colombia and its growth in cruise and container cargo traffic; and opening up of Cuba. The shipping industry is the major demand driver for bunkering. It should be noted that both container liner and cruise sector as the two largest demand segments are concentrated. Decision factors by ship operators with respect to bunkering operations and critical concerns can be summarised by 8 attributes: 1 Bunker quality 2 Market transparency (corruption free) 3 Bunker price competitiveness 4 Reliability and punctuality of bunker suppliers 5 Bunkering facilities and services (adequacy and efficacy) 6 Availability of all fuel grades including low-sulphur bunkers 7 Location of port 8 Government policies (e.g. quality control) and incentives Competitive Advantage Analysis and Competition Study Six determinants are used to analyse the competitive advantages of Jamaica’s bunkering sector and the findings are summarised as below. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 12

14) • Factor conditions: Factors include the entire bunker supply chain comprising of refineries, processors, blenders, storage tanks, etc. Jamaica’s bunker supply is dominated by few players which hold considerable bargaining power in the market structure. This could result in restrictions to market access, increasing market concentration and leading to the formation of an insular bunker cluster. • Demand conditions: Compared to the other major bunkering centres in the Caribbean, Jamaica’s shipping line customer mix relies on three major container carriers which are CMA CGM, MSC and ZIM. By comparison, Balboa and Puerto Manzanillo in Panama and Cartagena in Colombia have a more diverse mix of shipping line customers. Capability of meeting the needs of these customers will be an affirmation to the competitiveness of the Jamaican bunkering sector. However, transhipment cargo is notoriously footloose and this can shift within a short time period unless there are mechanisms to “lock-in” this key client. This is a key concern especially with both CMA CGM and MSC calling at several ports in the region. • Company strategy, firm structure and industry rivalry: A lack of viable domestic competition could lead to complacent service and uncompetitive prices, which in turn leads to stagnant or even lower bunkering demand. This in turns detracts other players from entering into the competition and further entrenching the monopolistic status of the incumbent and so the vicious cycle continues. • Related and supporting activities: The presence of internationally competitive suppliers in the bunker supply chain creates advantages for downstream suppliers. However, value created will be captured by one or two players in a monopolistic or oligopolistic setting. • Government policies: The key direction is to ensure an internationally competitive bunker supply chain with players operating in an open market structure. • Chance events: The uncontrollable factors include economic or financial crisis, surges of world/regional demand, uncertainty in shipping traffic, oil shocks, natural disaster, major technological discontinuities that reduce demand for bunkers, as well as political and social instability. The regional and international bunkering markets are analysed for benchmarking. For the Caribbean region, seven countries/locations are included in the analysis, namely Jamaica, Bahamas, Colombia, Panama, Puerto Rico, Suriname and Trinidad & Tobago. For international comparison, Singapore, Rotterdam and Houston are chosen due to their status as top bunkering centres in the world. Among the Caribbean bunkering centres, Panama is a major competitor to Jamaica. There are 20 bunker suppliers in Panama Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 13

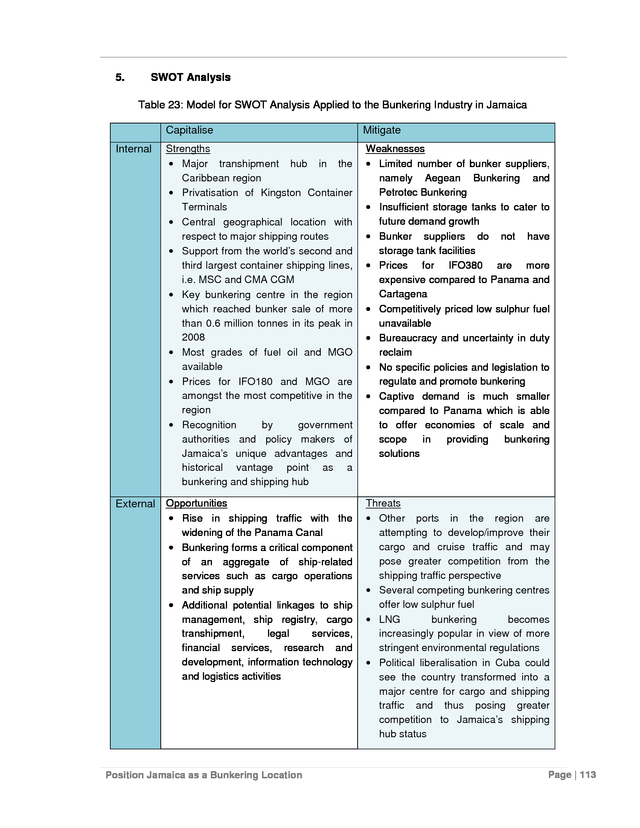

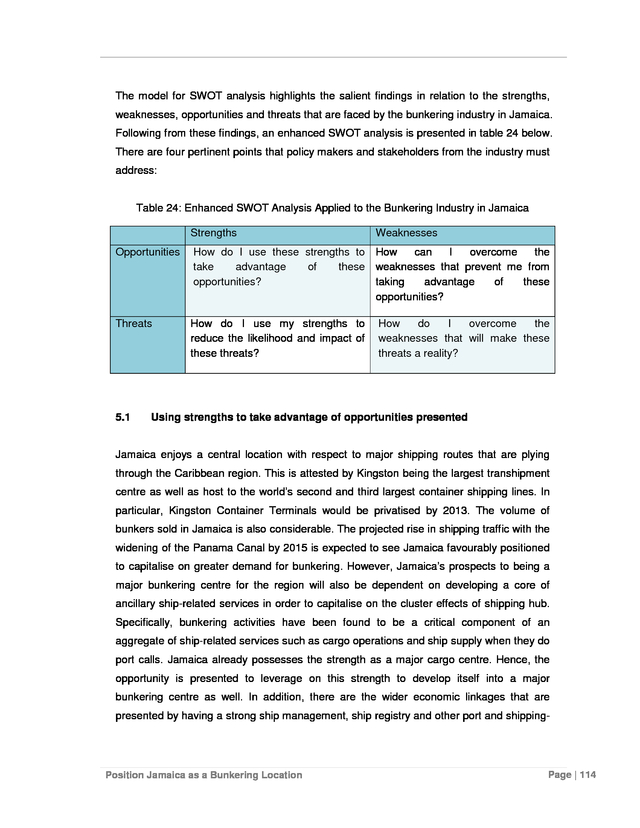

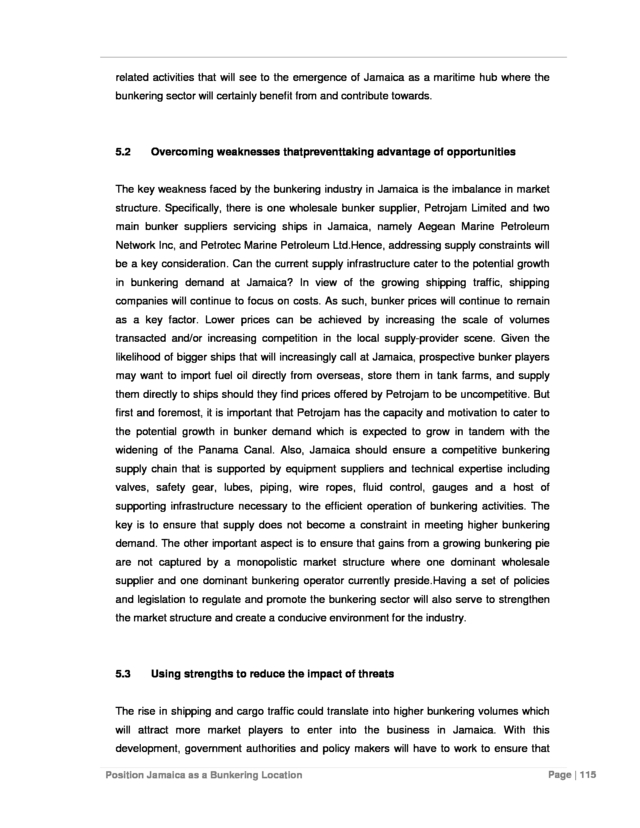

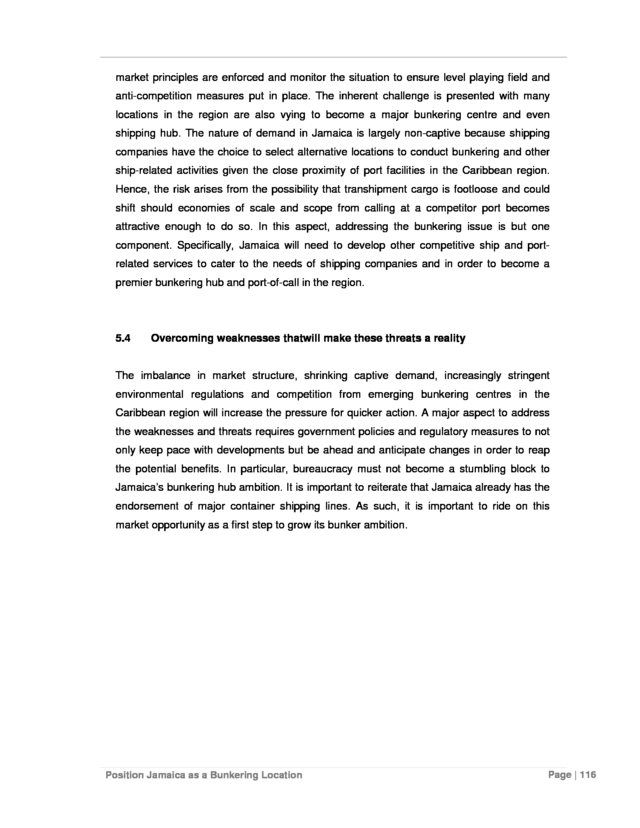

15) providing bunker in Colón, Cristobal and Balboa. This represents the widest variety of suppliers compared to other bunkering locations in the Caribbean region.Prices for IFO380 are some of the cheapest in the region. However, prices for other types of bunker fuel, particularly low sulphur products, are considerably more expensive. In addition to Panama’s strategic location,the wider variety of bunker fuel available is a major strength of Panama as a bunkering location vis-a-vis Jamaica. The major findings of competition dynamics analysis for Jamaica include high bargaining power of both customers (shipping lines) and bunkering service providers; presence of new competitors, namely Puerto Rico, Cartagena, Freeport, Puerto Caucedo and Cuba; and LNG as a cleaner and commercially viable alternative to sulphur-heavy marine fuel oil. SWOT Analysis Table 23 presents the SWOT Analysis. There are four pertinent points that policy makers and stakeholders from the industry must address: • Using strengths to take advantage of opportunities presented: Jamaica enjoys a central location with respect to major shipping routes that are plying through the Caribbean region. The projected rise in shipping traffic with the widening of the Panama Canal by 2015 is expected to see Jamaica favourably positioned to capitalise on greater demand for bunkering. • Overcoming weaknesses that prevent taking advantage of opportunities: There is one wholesale bunker supplier, Petrojam Limited and two main bunker suppliers servicing ships in Jamaica, namely Aegean Marine Petroleum Network Inc, and Petrotec Marine Petroleum Ltd. Hence, addressing supply constraints will be a key consideration. Having a set of policies and legislation to regulate and promote the bunkering sector will also serve to strengthen the market structure and create a conducive environment for the industry. • Using strengths to reduce the impact of threats: The rise in shipping and cargo traffic could translate into higher bunkering volumes which will attract more market players to enter into the business in Jamaica. With this development, government authorities and policy makers will have to work to ensure that market principles are enforced and monitor the situation to ensure level playing field and anti-competition measures put in place. • Overcoming weaknesses that will make these threats a reality: A major aspect to address the weaknesses and threats requires government policies and regulatory measures to not only keep pace with developments but be ahead and anticipate Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 14

16) changes in order to reap the potential benefits. In particular, bureaucracy must not become a stumbling block to Jamaica’s bunkering hub ambition. Environmental Impact Assessment, Regulatory Requirement and Quality Standards The environmental issue is analysed from four aspects. • Marine Environment:The National Environmental & Planning Agency (NEPA) highlights that Kingston, as a sheltered harbour, has been vulnerable to pollution, with the badly degraded water quality and introduction of alien species affecting the rich biodiversity of the harbour. Increasing bunkering activities and shipping traffic inevitably leads to negative marine environmental impacts from ballast water, fuel oil residue and waste disposal from ship operations as well as cargo residue. • Air-borne Environment:Exhaust gases are the primary source of emissions from vessels, releasing air greenhouse gases (GHG) such as CO2 (Carbon Dioxide), SOx (Sulphurous Oxide), NOx (Nitrous Oxide).MARPOL Annex VIintroduces stricter emission control areas (ECAs) to reduce emissions of those air pollutants further in designated sensitive sea areas. The sulphur limits will reduce from 3.5% m/m to 0.50% from 01 Jan 2020. • Land-based Environment: The development or improvement of a bunkering facility requires construction/extension of land-based facilities such as refineries, pipelines linking refinery to storage and jetties for the discharging and loading of bunker to the storage facility. • Hazard Risk Management & Response Measures: With the IMO’s “Prevention of Pollution during Transfer of Oil Cargo between Oil Tankers At Sea” coming into force from 01 Jan 2011, countries now have a consistent set of regulations to govern bunker operations. For hazard risk management to be effective however, the maritime and port authorities have to play a proactive role. Recommendations and Policy Action Plans Short term: 2 years 1. Establish central coordinating body for bunkering development Action item: As appointed by the government of Jamaica, MAJ to set up Bunker Strategy Teamto manage the development of Jamaica’s bunkering sector. The Team should be responsible in overseeing and monitoring the progress of the following policy action items in this section. Review of the policies’ implementation and the progress of Jamaica’s bunkering industry in the time frames of short, medium and longer term should be under the Team’s custody. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 15

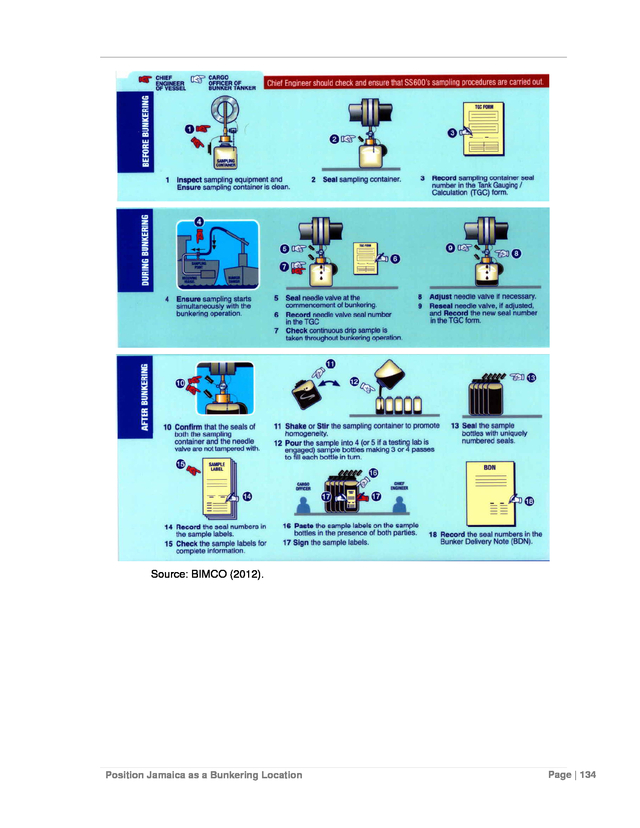

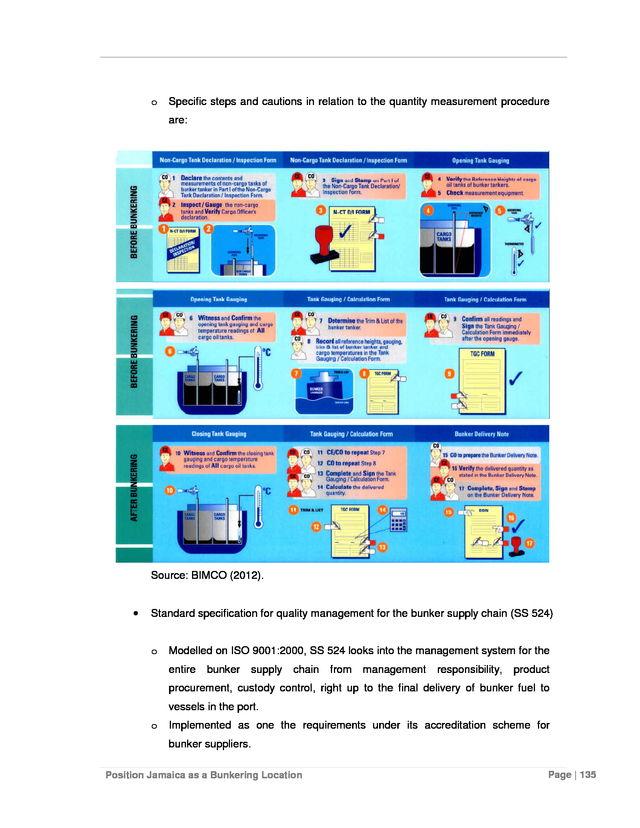

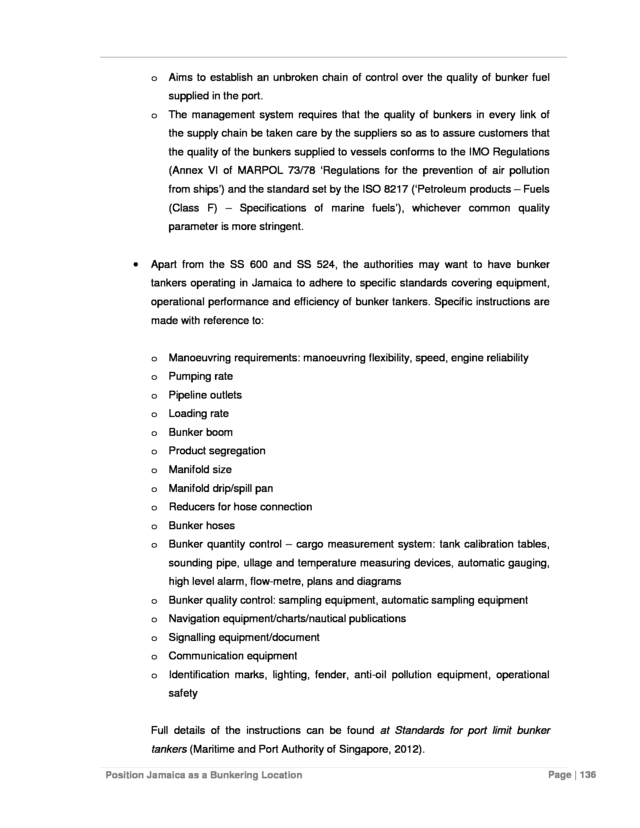

17) 2. Develop strong reputation and credibility for stringent bunkering standards Action item: Bunker Strategy Team to establish code of practice for bunkering, quality management system for bunker supply chain, and information guide for prospective market entrants made available through a web-link. 3. Supply low sulphur fuel Action item: Petrojam to supply low sulphur fuel to bunker operators; Bunker Strategy Team to facilitate the process when necessary. 4. Increasing capacity of fuel storage facilities Action item: Petrojam to install new fuel storage tank(s) in its premise in Kingston to cater future demand growth. Bunker operators may also install their own fuel storage tank(s) but approval has to be obtained from the government of Jamaica. Bunker Strategy Team should coordinate the future storage capacity at the national level to ensure that there will not be any excess supply due to lack of coordination. Government can offer incentive by giving interest-free loan to bunker suppliers who install new storage tank(s) by 2015 and those who install new storage tank(s) for storing low sulphur fuel. 5. Speed up dutyreclaim procedure and minimise bureaucracy Action item: Bunker Strategy Team to work with Customs to investigate the exact bottlenecks of dutyreclaim; and to work with the Ministry of Labour and Social Security to speed up work permit arrangements. Resolving issues in duty reclaim should be done by end 2013 before petroleum free zones can be officially established. In terms of work permit,the Ministry of Labour and Social Security can have a pre-approval list for seafarers based on the country that issues the Certificate of Competency. Recommendation can be obtained from MAJ in forming the pre-approval list. It is important to establish clear guidelines on duty reclaim and work permit application procedures including estimated time required for approval. 6. Develop petroleum free zones Action item: WithBunker Strategy Team’s assistance, the Ministry of Investment, Industry and Commerce is to add petroleum as a product under the Free Zone Act. Bunkers canenter and leave the free zone without having to pay taxes, provided that sales are destined to the international market. Customs is to implement monitoring system to ensure the integrity of bunker suppliers and operators. 7. Develop competitive market structure Action item: MAJ to discuss with Petrojam on wholesale bunker supply’s market structure; Bunker Strategy Team to actively reach out to prospective bunker suppliers and facilitate business start up; Bunker Strategy Team to meet with current bunker suppliers and operators regularly (e.g. twice a year) to understand their needs and facilitate their business. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 16

18) 8. Connecting the bunkering community and publicity campaign Action item: Bunker Strategy Team to set up Bunker Quality Advisory Panel which meets regularly (e.g. twice a year); Bunker Strategy Team can work together with JAMPRO to organise public forum for the bunkering and shipping community annually.The efforts should be started within 1 year, and to be continued throughout medium and long terms. 9. Human capital development for bunkering Action item: Bunker Strategy Team and MAJ to partner with training institutes in providing student education and executive training for the skill sets required; Individual companies and government agencies to support scholarships for attracting young talents, as well as staff training and development for upgrading human resources. The efforts should be started within 2 years, and to be continued throughout medium and long terms. Medium term: 5 years 1. Legislative framework for shipping, logistics and business at large Action item:Bunker Strategy Team to work together with the Ministry ofInvestment, Industry and Commerce, other government agencies and stakeholders to establish a legislative framework for shipping, logistics and business at large. 2. Global drive towards environmentally-friendly shipping Action item: Bunker Strategy Team to discuss with Petrojam on sourcing LNG; to develop licensing requirements for bunker suppliers to supply LNG to ships. Medium to longer term: 5 to 10 years 1. Develop comprehensive suite of ship-related services Action item: MAJ to work with government ministries, authorities and stakeholders to develop comprehensive suite of ship-related services, including ship survey, ship repair and crew change; to anchor Jamaica’s status as a premier shipping hub in the Caribbean region. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 17

19) 1. Introduction In 2010, the Commonwealth Secretariat conducted a study and developed a framework to position Jamaica as a shipping hub. The report entitled ‘Development of a Frameworkfor Positioning Jamaicaas a Shipping Hub’ by the Commonwealth Secretariat had identified Jamaica as an active maritime centre with a bunkering station with considerable growth potential. The report also noted the importance of the shipping industry as a significant contributor to the country’s economy. Furthermore, the strategic location of Kingston port to benefit from north-south and east-west shipping routes has seen the facility benefiting from the transhipment, ship registry, cruise and maritime training aspects. This development also points to the strong potential of Jamaica to become a truly competitive maritime centre comprising a host of other maritime and related activities that include shipping services, marine insurance, banking, legal services, dry docking and bunkering. In an attempt to achieve the targets in the Government of Jamaica’s long term National Development Plan and its Growth Enhancement Strategy, the Planning Institute of Jamaica has requested on behalf of the Maritime Authority further assistance to conduct a study which inter alia, will quantify the benefits of positioning Jamaica as a bunkering hub in the region.In October 2012, the Commonwealth Secretariat appointed Nanyang Technological University (Singapore) as consultants to undertake a study to position Jamaica as a bunkering location in the Caribbean Region. The findings presented in this report are obtained from thorough research, based on various sources including interviews with stakeholders involved in or related to the maritime and bunkering industries in Jamaica to understand the situation of the bunkering industry in Jamaica. The consultants appreciate MAJ’s arrangements they made during the consultants’ visits to Kingston. The consultants are also thankful to the individuals and organisations that shared their views and information contributing to the preparation of this report. 2. Purpose and Description of the Project Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 18

20) The main objective of the project is to conduct a market development study on bunkering in Jamaica which will enable Jamaica to increase its regional market share. There are five parts of the study, namely, Part 1: Economic Impact Analysis and Market Assessment Part 2: Environment Scan, Competitive Advantage Analysis and Competition Study Part 3: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Analysis Part 4: Environmental Impact Assessment and Regulatory Requirement Part 5: Recommendations and Policy Action Plans 3. Economic Impact Analysis and Market Assessment 3.1 Economic impact analysis A successful and competitive bunkering hub will have a positive impact on the dynamism of the Jamaican maritime cluster. More importantly, thestudy recognises that bunkering activities do not operate in isolation but form an important eco-system within the entire maritime cluster. Her ability to thrive will be dependent on the overall health of other activities within the cluster as well as her ability to contribute positively in competitive terms to support the cluster. For the purpose of this study, the analyses shall examine the economic impact of the bunkering sector with reference to: (a) Direct impact: Results directly from bunkering operations to ships carried out in Jamaica’s bunkering sector, such as services provided to shipping companies taking bunker. (b) Indirect impact: Arises from the purchase of goods and services and other forms of spending made by firms which produce the direct impact. (c) Induced impact: Results from the purchases of goods and services and other forms of spending made by individuals employed by firms linked directly to bunkering activities. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 19

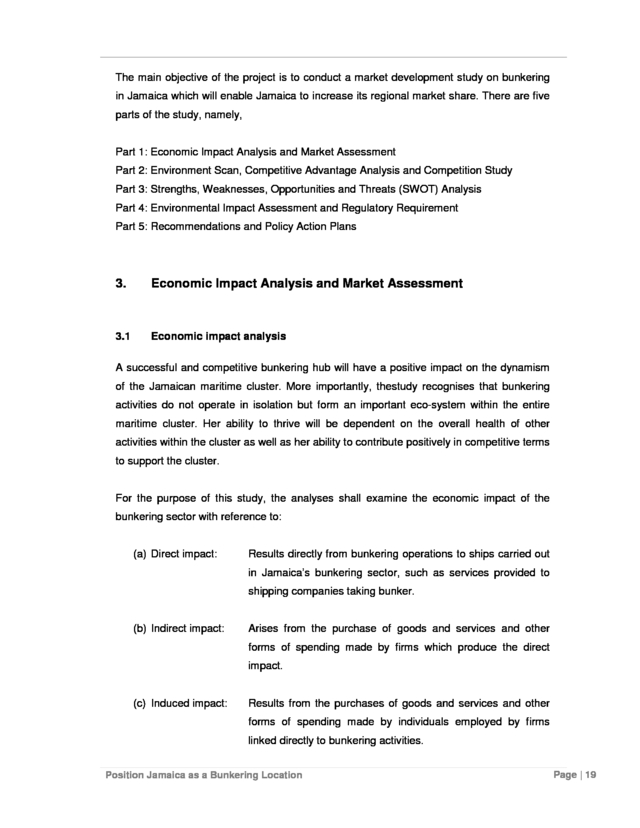

21) The results of these impacts will be presented in terms of total business revenue generated, employment, and value added contribution to GDP. 3.1.1 Overview of current bunkering operations in Jamaica Table 1: Bunker ExportSales in Jamaica (2005-2012) Barrels Marine Intermediate Gas Oil Fuel Oil 2005 143,695 643,648 2006 352,364 2007 Metric Tonnes Marine Intermediate Gas Oil Fuel Oil 787,343 19,058 98,719 117,777 2,547,483 2,899,847 46,733 390,718 437,451 550,523 3,514,948 4,065,471 73,014 539,102 612,116 2008 275,628 3,915,064 4,190,692 36,555 600,470 637,025 2009 286,803 3,368,486 3,655,289 38,038 516,639 554,677 2010 200,032 1,720,110 1,920,142 26,529 263,821 290,350 2011 169,949 1,716,656 1,886,605 22,540 263,291 285,831 2012 149,284 1,298,455 1,447,739 19,799 199,150 218,949 Total Total Source: Petrojam(2013). According to data from Petrojam, 0.22 million tonnes of bunker fuel was sold in 2012 (see table 1). Although the figure is almost twice the volume of 0.12 million tonnes of bunker fuel sold in 2005, it is significantly lower compared to the peak of 0.64 million tonnes sold in 2008. In Cumulative Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) terms, the trend represents a growth of 9.3% in the 8-year period since 2005 and leading up to 2012. The reduction in bunker sales in Jamaica from 2008 to 2010 is in part related to the major global economic recession which started from the third quarter of 2008. The recession was particularly severe for more developed economies such as the US.Those countries that were dependent on exports to the US saw their seaborne trade curtailed to various degrees. Since shipping is a derived demand of the world economy, global shipping traffic which fell during the period also adversely affected the demand for bunkers. Thus the bunkering industry is sensitive to economic performance and shipping traffic. But a competitive Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 20

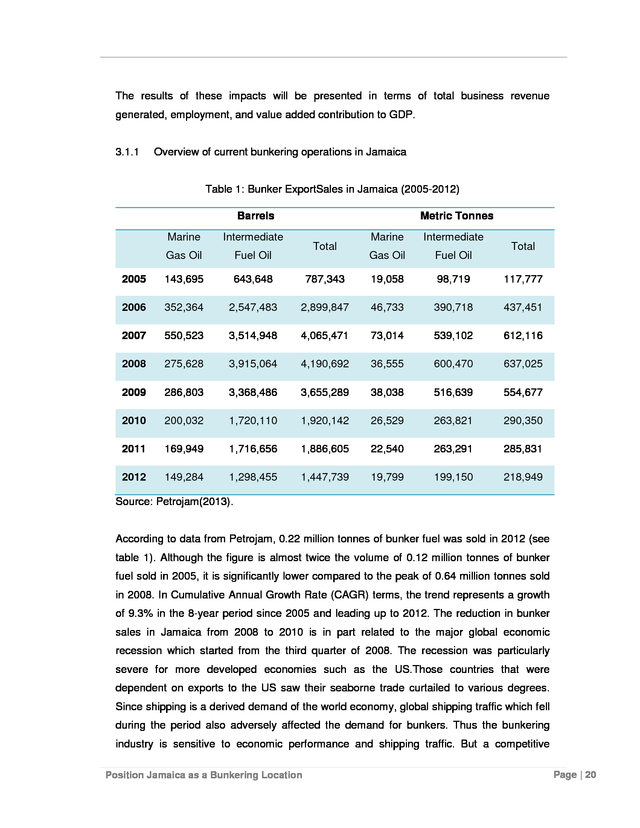

22) bunkering location would be able to lower its sensitivity to these factors. On this note, a competitive advantage analysis will be presented in section 4. More important point to note is that although the current bunker export sales has declined relative to its peak in 2008, the statistics show that Jamaica could reach higher bunker sales and has the potential to revive its bunkering sector. 3.1.2 Direct economic impact Table 2: Direct Economic Impact of the Bunkering Sector in Jamaica Indicator Bunker sales Total business revenue generated Bunkering’s share of GDP by business revenue Bunkering’s contribution to GDP by value added Bunkering’s share of GDP by value added 2011 285,831 metric tonnes US$209.1 million 1.443% US$2.74 million 0.019% Total employment About30 people Jamaica’s GDP US$14.49 billion Sources: Contribution is based on consultants’ estimation, with data fromPetrojam (2013) and International Monetary Fund (2012). Direct economic impact is generated as a result of direct spending by firms on bunkering operations carried out in Jamaica’s bunkering sector. Based on almost 285,831 metric tonnes of bunker supplied in 2011, total business revenue generated is estimated at US$209.1 million (see table 2). This puts the direct economic impact for business revenue generated from bunker sales at 1.44% of Jamaica’s GDP.In terms of direct value added (that is, net profit) contribution to GDP, bunkering activities are estimated to contribute US$2.74 million or 0.02% of the country’s GDP in 2011. As for employment, the present bunkering sector is estimated to employ about30 people based on the assumption of productivity employee at 10,000-15,000 metric tonne sales per annum. As the exact data is unavailable for Jamaica, the estimates are derived with reference to the bunkering sector’s economic impact in Singapore which is shown in table 3.Singapore is a transhipment hub situated in a strategic geographical location. This characteristic is similar Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 21

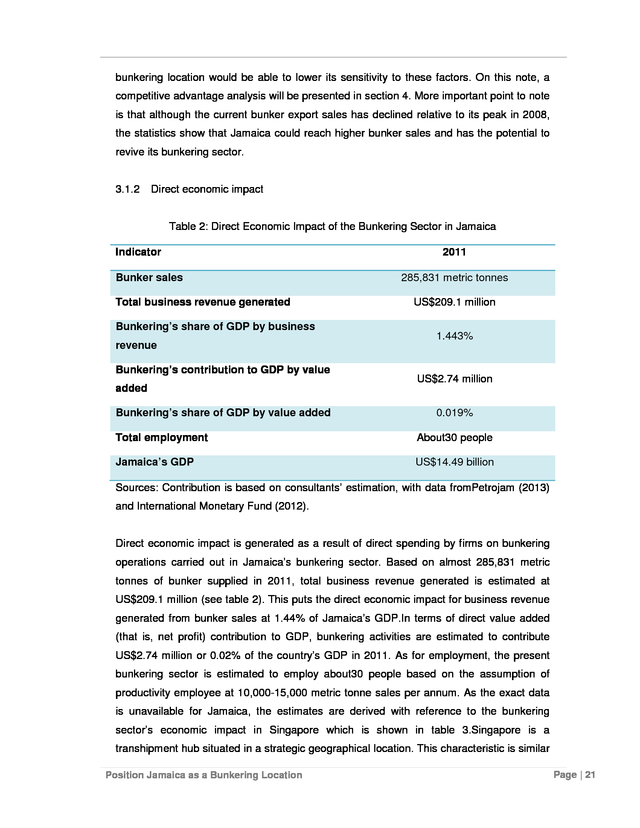

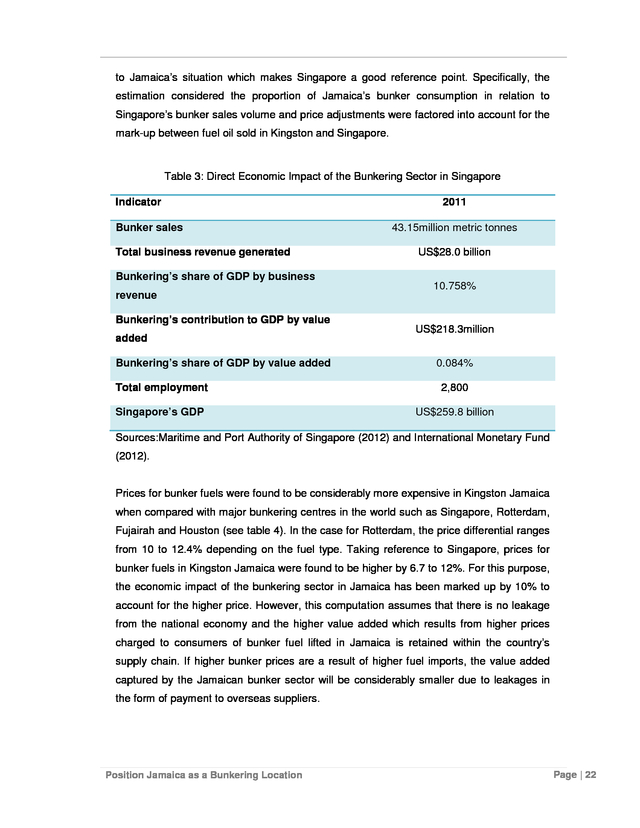

23) to Jamaica’s situation which makes Singapore a good reference point. Specifically, the estimation considered the proportion of Jamaica’s bunker consumption in relation to Singapore’s bunker sales volume and price adjustments were factored into account for the mark-up between fuel oil sold in Kingston and Singapore. Table 3: Direct Economic Impact of the Bunkering Sector in Singapore Indicator Bunker sales Total business revenue generated Bunkering’s share of GDP by business revenue Bunkering’s contribution to GDP by value added Bunkering’s share of GDP by value added 2011 43.15million metric tonnes US$28.0 billion 10.758% US$218.3million 0.084% Total employment 2,800 Singapore’s GDP US$259.8 billion Sources:Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (2012) and International Monetary Fund (2012). Prices for bunker fuels were found to be considerably more expensive in Kingston Jamaica when compared with major bunkering centres in the world such as Singapore, Rotterdam, Fujairah and Houston (see table 4). In the case for Rotterdam, the price differential ranges from 10 to 12.4% depending on the fuel type. Taking reference to Singapore, prices for bunker fuels in Kingston Jamaica were found to be higher by 6.7 to 12%. For this purpose, the economic impact of the bunkering sector in Jamaica has been marked up by 10% to account for the higher price. However, this computation assumes that there is no leakage from the national economy and the higher value added which results from higher prices charged to consumers of bunker fuel lifted in Jamaica is retained within the country’s supply chain. If higher bunker prices are a result of higher fuel imports, the value added captured by the Jamaican bunker sector will be considerably smaller due to leakages in the form of payment to overseas suppliers. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 22

24) Nonetheless, the report notes that Jamaica is also strategically located to capitalise on bunkering opportunities offered by the major shipping lanes that ply in the region. Hence, there is scope for stronger growth for the island’s bunkering sector if the price competitiveness issue can be addressed. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 23

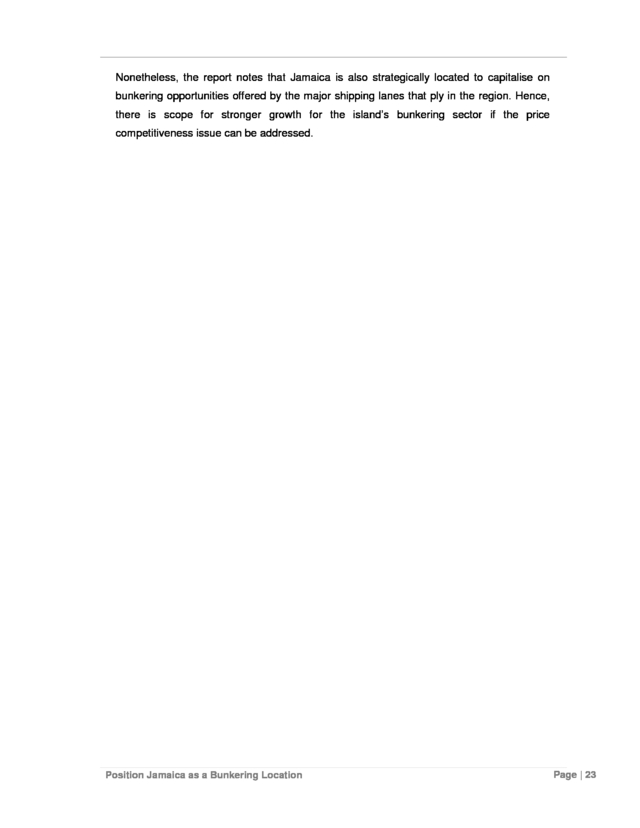

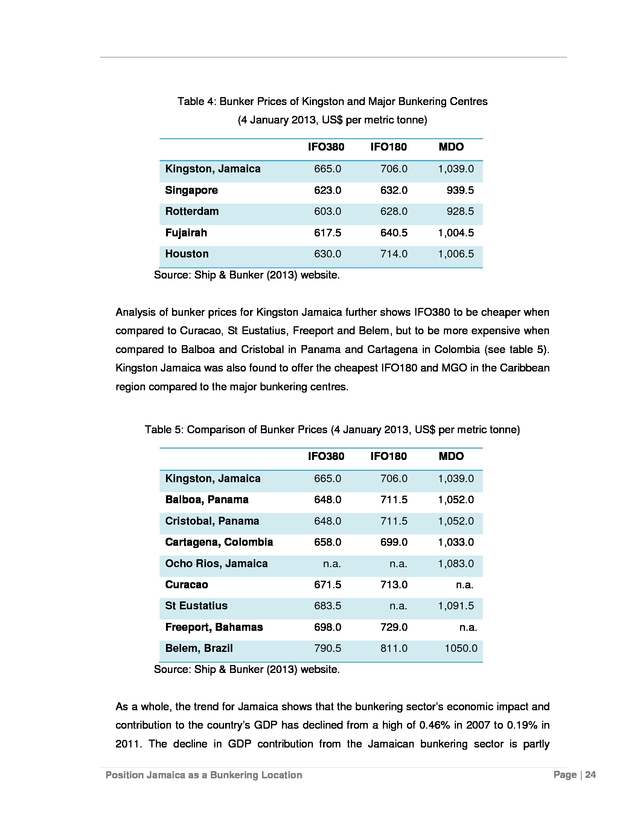

25) Table 4: Bunker Prices of Kingston and Major Bunkering Centres (4 January 2013, US$ per metric tonne) IFO380 IFO180 MDO Kingston, Jamaica 665.0 706.0 1,039.0 Singapore 623.0 632.0 939.5 Rotterdam 603.0 628.0 928.5 Fujairah 617.5 640.5 1,004.5 Houston 630.0 714.0 1,006.5 Source: Ship & Bunker (2013) website. Analysis of bunker prices for Kingston Jamaica further shows IFO380 to be cheaper when compared to Curacao, St Eustatius, Freeport and Belem, but to be more expensive when compared to Balboa and Cristobal in Panama and Cartagena in Colombia (see table 5). Kingston Jamaica was also found to offer the cheapest IFO180 and MGO in the Caribbean region compared to the major bunkering centres. Table 5: Comparison of Bunker Prices (4 January 2013, US$ per metric tonne) IFO380 IFO180 Kingston, Jamaica 665.0 706.0 1,039.0 Balboa, Panama 648.0 711.5 1,052.0 Cristobal, Panama 648.0 711.5 1,052.0 Cartagena, Colombia 658.0 699.0 1,033.0 n.a. n.a. 1,083.0 Curacao 671.5 713.0 n.a. St Eustatius 683.5 n.a. 1,091.5 Freeport, Bahamas 698.0 729.0 n.a. Belem, Brazil 790.5 811.0 1050.0 Ocho Rios, Jamaica MDO Source: Ship & Bunker (2013) website. As a whole, the trend for Jamaica shows that the bunkering sector’s economic impact and contribution to the country’s GDP has declined from a high of 0.46% in 2007 to 0.19% in 2011. The decline in GDP contribution from the Jamaican bunkering sector is partly Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 24

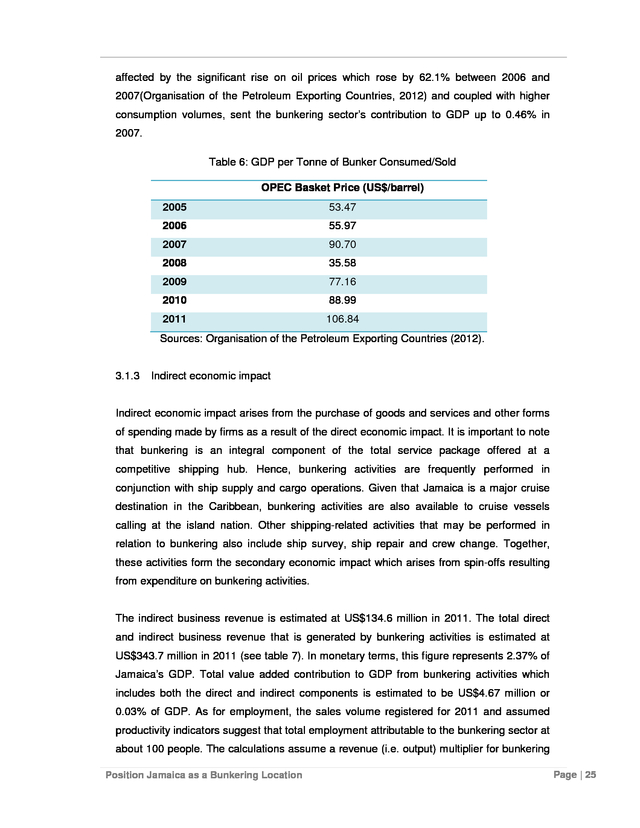

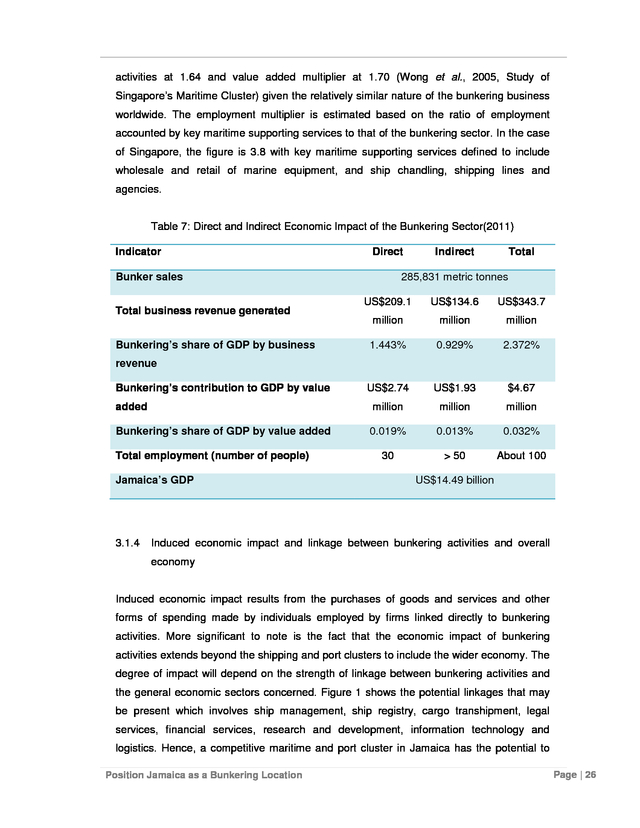

26) affected by the significant rise on oil prices which rose by 62.1% between 2006 and 2007(Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, 2012) and coupled with higher consumption volumes, sent the bunkering sector’s contribution to GDP up to 0.46% in 2007. Table 6: GDP per Tonne of Bunker Consumed/Sold OPEC Basket Price (US$/barrel) 2005 53.47 2006 55.97 2007 90.70 2008 35.58 2009 77.16 2010 88.99 2011 106.84 Sources: Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (2012). 3.1.3 Indirect economic impact Indirect economic impact arises from the purchase of goods and services and other forms of spending made by firms as a result of the direct economic impact. It is important to note that bunkering is an integral component of the total service package offered at a competitive shipping hub. Hence, bunkering activities are frequently performed in conjunction with ship supply and cargo operations. Given that Jamaica is a major cruise destination in the Caribbean, bunkering activities are also available to cruise vessels calling at the island nation. Other shipping-related activities that may be performed in relation to bunkering also include ship survey, ship repair and crew change. Together, these activities form the secondary economic impact which arises from spin-offs resulting from expenditure on bunkering activities. The indirect business revenue is estimated at US$134.6 million in 2011. The total direct and indirect business revenue that is generated by bunkering activities is estimated at US$343.7 million in 2011 (see table 7). In monetary terms, this figure represents 2.37% of Jamaica’s GDP. Total value added contribution to GDP from bunkering activities which includes both the direct and indirect components is estimated to be US$4.67 million or 0.03% of GDP. As for employment, the sales volume registered for 2011 and assumed productivity indicators suggest that total employment attributable to the bunkering sector at about 100 people. The calculations assume a revenue (i.e. output) multiplier for bunkering Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 25

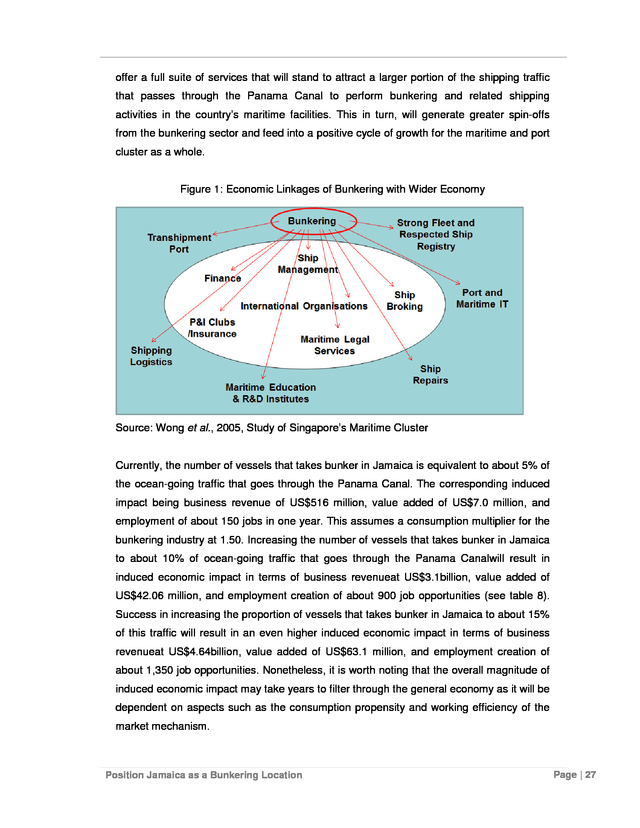

27) activities at 1.64 and value added multiplier at 1.70 (Wong et al., 2005, Study of Singapore’s Maritime Cluster) given the relatively similar nature of the bunkering business worldwide. The employment multiplier is estimated based on the ratio of employment accounted by key maritime supporting services to that of the bunkering sector. In the case of Singapore, the figure is 3.8 with key maritime supporting services defined to include wholesale and retail of marine equipment, and ship chandling, shipping lines and agencies. Table 7: Direct and Indirect Economic Impact of the Bunkering Sector(2011) Indicator Direct Indirect Total 285,831 metric tonnes Bunker sales US$209.1 US$134.6 US$343.7 million million million 1.443% 0.929% 2.372% US$2.74 US$1.93 $4.67 added million million million Bunkering’s share of GDP by value added 0.019% 0.013% 0.032% 30 > 50 About 100 Total business revenue generated Bunkering’s share of GDP by business revenue Bunkering’s contribution to GDP by value Total employment (number of people) Jamaica’s GDP 3.1.4 US$14.49 billion Induced economic impact and linkage between bunkering activities and overall economy Induced economic impact results from the purchases of goods and services and other forms of spending made by individuals employed by firms linked directly to bunkering activities. More significant to note is the fact that the economic impact of bunkering activities extends beyond the shipping and port clusters to include the wider economy. The degree of impact will depend on the strength of linkage between bunkering activities and the general economic sectors concerned. Figure 1 shows the potential linkages that may be present which involves ship management, ship registry, cargo transhipment, legal services, financial services, research and development, information technology and logistics. Hence, a competitive maritime and port cluster in Jamaica has the potential to Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 26

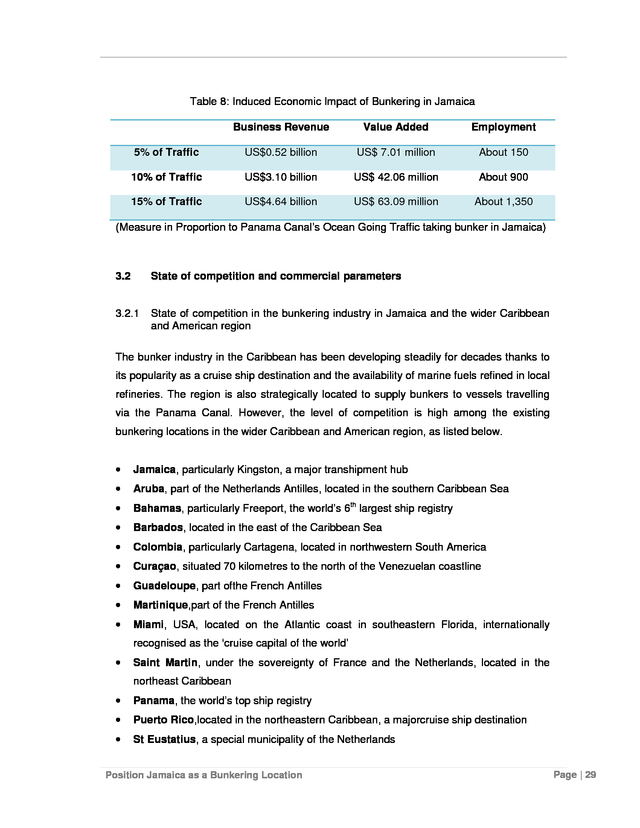

28) offer a full suite of services that will stand to attract a larger portion of the shipping traffic that passes through the Panama Canal to perform bunkering and related shipping activities in the country’s maritime facilities. This in turn, will generate greater spin-offs from the bunkering sector and feed into a positive cycle of growth for the maritime and port cluster as a whole. Figure 1: Economic Linkages of Bunkering with Wider Economy Source: Wong et al., 2005, Study of Singapore’s Maritime Cluster Currently, the number of vessels that takes bunker in Jamaica is equivalent to about 5% of the ocean-going traffic that goes through the Panama Canal. The corresponding induced impact being business revenue of US$516 million, value added of US$7.0 million, and employment of about 150 jobs in one year. This assumes a consumption multiplier for the bunkering industry at 1.50. Increasing the number of vessels that takes bunker in Jamaica to about 10% of ocean-going traffic that goes through the Panama Canalwill result in induced economic impact in terms of business revenueat US$3.1billion, value added of US$42.06 million, and employment creation of about 900 job opportunities (see table 8). Success in increasing the proportion of vessels that takes bunker in Jamaica to about 15% of this traffic will result in an even higher induced economic impact in terms of business revenueat US$4.64billion, value added of US$63.1 million, and employment creation of about 1,350 job opportunities. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the overall magnitude of induced economic impact may take years to filter through the general economy as it will be dependent on aspects such as the consumption propensity and working efficiency of the market mechanism. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 27

29) Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 28

30) Table 8: Induced Economic Impact of Bunkering in Jamaica Business Revenue Value Added Employment 5% of Traffic US$0.52 billion US$ 7.01 million About 150 10% of Traffic US$3.10 billion US$ 42.06 million About 900 15% of Traffic US$4.64 billion US$ 63.09 million About 1,350 (Measure in Proportion to Panama Canal’s Ocean Going Traffic taking bunker in Jamaica) 3.2 State of competition and commercial parameters 3.2.1 State of competition in the bunkering industry in Jamaica and the wider Caribbean and American region The bunker industry in the Caribbean has been developing steadily for decades thanks to its popularity as a cruise ship destination and the availability of marine fuels refined in local refineries. The region is also strategically located to supply bunkers to vessels travelling via the Panama Canal. However, the level of competition is high among the existing bunkering locations in the wider Caribbean and American region, as listed below. • Jamaica, particularly Kingston, a major transhipment hub • Aruba, part of the Netherlands Antilles, located in the southern Caribbean Sea • Bahamas, particularly Freeport, the world’s 6th largest ship registry • Barbados, located in the east of the Caribbean Sea • Colombia, particularly Cartagena, located in northwestern South America • Curaçao, situated 70 kilometres to the north of the Venezuelan coastline • Guadeloupe, part ofthe French Antilles • Martinique,part of the French Antilles • Miami, USA, located on the Atlantic coast in southeastern Florida, internationally recognised as the ‘cruise capital of the world’ • Saint Martin, under the sovereignty of France and the Netherlands, located in the northeast Caribbean • Panama, the world’s top ship registry • Puerto Rico,located in the northeastern Caribbean, a majorcruise ship destination • St Eustatius, a special municipality of the Netherlands Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 29

31) • St Kitts, the smallest nation in the Americas • Suriname, in northern South America • Trinidad & Tobago, an archipelagic state in the southern Caribbean • Venezuela, on the northern coast of South America, state owned PDVSA is a major playerin the global oil market • Virgin Islands,form the border between the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, a popular destination for cruise ships and yachts The profiles of the major competitor bunkering centres will be presented in Section 4. 3.2.2 Emerging competition to note Cuba As the Caribbean’s second largest island, Cuba’s prime location should make it an ideal theoretical bunker station. However, the political regime stopped it to be international shipping and bunkering centre. The US trade embargo set up against Cuba in the 1960s has stopped American companies exploring the potential of the Cuban market.However, although theembargo is still in effect, there is asignificant movement in the US Congressto lift these restrictions because, despitethe fact the embargo remains in place,relaxation of the restrictions has resultedin the US becoming one of Cuba’s top 10trading partners, while other countriesare still penalised for exporting goods tothe island.As soon as travel and trade restrictions with Cuba are lifted, or relaxed, by the US Government there is likely to be a surge of investment and development in order to take advantage of Cuba’s location so close to the USA and an abundance of relatively low wage labour. As such, shipping traffic will increase accordingly which in turn stimulates ship-related activities including bunkering. Jamaica's nearest competition for trans-shipment activity is Cuba, which is embarking on a US$800-million port expansion in Mariel. The Canadian company Reiter Petroleum has an agreement with state-owned company Cuba Petroleum (CUPET), which operates the country’s main Havana-based refinery, to market bunkers to foreign flag vessels. The company also undertakes bunkers and lubricants supplies to Cuban vessels. Meanwhile, Reiter Petroleum handles between 80 million and 100 million barrels of fuel oil sales each year. 380 cst and 180 cst intermediate fuel oil (IFO), as well as marine gasoline (MGO) are produced in Cuba and readily available at the country’s main port in Havana. Much of the Cuban bunker industry is reliant on the traffic seen at the port of Havana. The portreceives Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 30

32) its supply from three bunker barges, ranging in size from 545 m3 to 800 m3 capacities,with MGO also able to be supplied by truck at truck accessible docks. 3.2.3 Competitiveness of current bunker supply and service providers in Jamaica There is one wholesale bunker supplier, Petrojam Limited and two main bunker suppliers servicing ships in Jamaica, namely Aegean Marine Petroleum Network Inc, and Petrotec Marine Petroleum Ltd. Petrojam Limited is established in 1982 and jointly owned by Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) and the Petroleum Corporation of Jamaica (PCJ). As Jamaica’s national sole oil refinery, it is located along the shoreline of the Kingston Harbour on a 76-acre site. Petrojam produces a range of oil products, sourcing crude supplies mainly from Venezuela, Mexico and Ecuador. Petrojam is the solewholesale bunker supplier selling bunkers to the two bunker delivery operators in Jamaica.In other words, Petrojam is in a monopolistic position. Hence government policy is required to ensure the competitiveness of Petrojam. Jamaica’s petroleum product prices are indexed to the US Gulf Coast Reference Prices, which report on the prices of finished products.Petrojam’s ex-refinery pricing arrangement is in keeping with the Government of Jamaica’s policy that Petrojam must be the least cost option for the supply of petroleum and petroleum products to Jamaica on a sustained basis.The ex-refinery pricing formula ensures transparency and competitive prices. Petrojam does not always refine the finished products that are sold as the company sometimes finds it necessary to import the products when it is more cost efficient to do so. Finished oil products are imported primarily from Trinidad and Tobago. However, Petrojam does not offer low sulphur fuel at the moment. Aegean Marine Petroleum Network Inc. is a Greece-based marine fuelcompany which supplies bunker oil and lubricants to ships in ports and at sea. The company is well established withoperations in 17 markets globally. In Jamaica, bunker delivery services are provided at Kingston, Ocho Rios and Montego Bay.All grades of bunker fuels are available, from 30 to 380 Cst and MGO, except for low sulphur fuel. All products supplied in Jamaica meet ISO 8217/2005 standardsincorporating the latest amendment for max allowable sulphur content, IFO 3.5%, MGO 1.5%, and are in compliance with Marpol 73/78, Annex VI. It is desirable for Jamaica to have a globally competitive bunker supplier stationed in the country. However, Aegean also operates in Panama and Trinidad & Tobago – two of the major competitors to Jamaica in the Caribbean region. Aegean is currently operating at a much larger scale than the new bunker supplier Petrotec. A fair Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 31

33) market environment will be able to ensure that the dominant market player also operates at its optimal competitive capacity in Jamaica. Petrotec Marine Petroleum Ltdis a new petroleum company which aims to sell bunkers in base station Kingston, Jamaica primarily. Petrotec can supply two grades of marine fuels, IFO RMG 380 Cst and MGO DMA. Other grades such as, IFO 180, 120, 60, 30 Cst are also available on request. Same as Aegean,Petrotec’s products are complied with ISO 8217/2005standards. Its vision for 2020 is to become one of the five largest bunker companies in the Caribbean. It is in the company’s plans to have a new and larger bunker vessel in the near future, aiming to service the bunker needs of cruise vessels and other potential customers on the North coast of Jamaica. A third bunker vessel will be added to serve the needs of the base station and the entire island. In view of the expansion developments of the Panama Canal, Petrotec intends to add more vessels to cover the expected additional demands in the ports of Jamaica. It can be seen that Petrotec, although being a new market player, is actively advancing its competitive position through more investment in acquiring assets. 3.3 Demand conditions and market dynamics Since bunkering is a service for ships, demand and market analysis in this section shall focus on vessel calls and shipping traffic. 3.3.1 Size of demand According to Port Authority of Jamaica, by November 2012, total vessel visits by major facility and port of call in Jamaica had reached 3,335. Kingston Container Terminal alone contributed 42% of the total visits, making it the most visited facility, followed by Kingston Wharves (779 visits), Kingston Sufferance Wharves (359 visits) and Montego Bay(245 visits). Volume of visits fluctuated slightly throughout the year with yearly high 338 visits in March and yearly low 278 visits in May. In 2011, the yearly high visits also occurred in March (Port Authority of Jamaica, 2012). From historical data, total vessel visits in major port facilities in Jamaica declined by 5.8% from 2008 to 2009 but quickly recovered with a 7.0% growth in 2010. It remained at almost the same level in 2011(-0.3%) and in 2012 (+0.5% compared with same period in 2011). In 2012, Most port facilities attracted similar levels of visits as in 2011 with exceptions in Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 32

34) Kingston Sufferance Wharves (up by 14%), Montego Bay(down by 9.3%), Rocky Point(down by 14.3%) and Port Esquivel(down by 14%). 3.3.2 Composition of demand Vessel visits to the major port facilities in Jamaica can be classified into three categories: cargo vessel visits, cruise ship calls and miscellaneous vessel visits. Cargo vessel visit is the largest among the three groups, responsible for 84.2% of the total visits from 2008 to 2012. The second largest sector is cruise vessel visit, which on average contributes 10% to the total visits. Miscellaneous vessel visits account for the rest at 5.8%. Since 2010, there has been a decline in the share of cargo vessel visits, shrinking from 87.1% in 2010 to 82.1% in 2012. The share of cruise vessel visits has remained relatively unchanged since 2009 while the share of miscellaneous vessel visits has increased from 3.9% in 2010 to 7.9% in 2012. However, there is difference in composition of demand in the different portfacilities. For example, according to Corporate Planning & Research Department, Port Authority of Jamaica, cruise visits accounted for only 0.03% of total vessel visits in Kingston, which is far from the average 10%. In the case of Kingston, container vessels are the most frequent visitors, accounting for 75.2% of the total vessel visits in Kingston in 2012, followed by dry bulk carriers (6.6%), tankers (5.5%) and RO/RO ships (3.5%). General cargo vessels contributed 2.2% of the total vessel visits. One fact worth noticing is that, although container is the dominant type of ship visiting Kingston, its percentage of total visits has been declining since 2010, from 78.5% in 2010 to 75.2% in 2012. Within the container vessel segment, the bulk of ship calls are accounted by three shipping lines, namely, CMA CGM, ZIM and Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) (Informa UK Limited, 2012). As of 31st December 2012, CMA CGM and ZIM each has 30 vessels calling at Kingston whereas MSC has 12 vessels calling per week. However, the largest vessels calling at Kingston are deployed by MSC ranging up to 6,730 TEUs in size. These vessels are deployed in the East Coast South America 1/New Tango Service which is jointly operated by MSC and CSAV. The service connects mainly between New York City and Savannah on the eastern seaboard in the United States and Brazil and turns around in the Rio de la Plata region. Kingston serves as a major hub as it allows for relaying of cargo between the north-south and east-west shipping routes. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 33

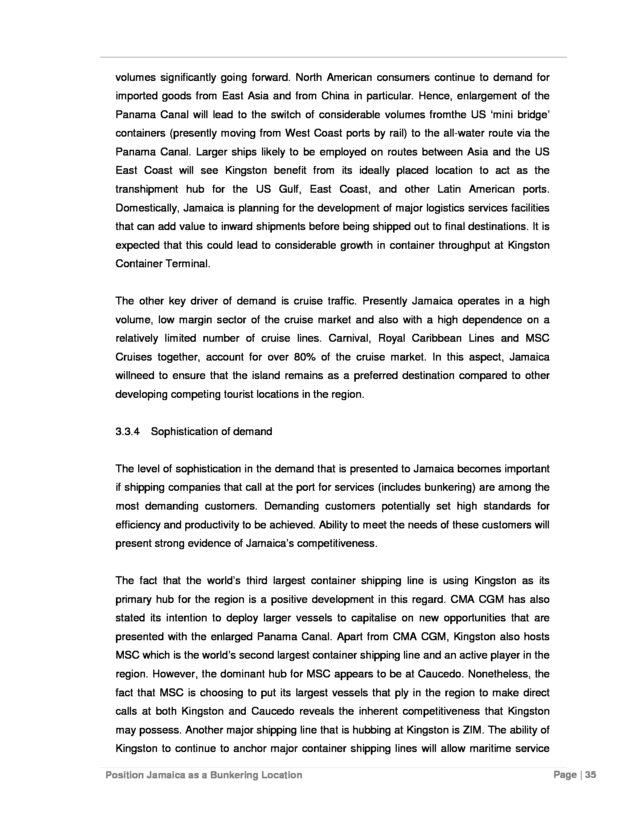

35) 3.3.3 Drivers of demand and accompanying trends and development A key driver of the growth in demand is container shipping. However, the demand has been declining as seen in Jamaica’s largest terminal, Kingston Container Terminal. There could be two main reasons for this decline. Firstly, more direct calls at Central and South American ports have reduced the need for transhipment via a way port such as Kingston. As containerisation has grown in South America and cargo volumes are now providing a sufficient load base, it has become economical for container service providers to call direct rather than rely on transhipment for certain ports. Secondly, Kingston is facing more intense competition from other transhipment hubs in the region including Freeport, Bahamas; Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago; Caucedo, Dominican Republic; Panama; and Colombia. Nonetheless, Kingston has managed to increase its overall share of the container port market in the Caribbean from 24% in 2005 to 27% in 2010 (see figure 2). By comparison, San Juan and Freeport saw their container market share decline or remaining stagnant in the same period. Hence, transhipment-wise, Kingston is expected to remain among the largest container hub in the region especially with the support of CMA CGM. Figure 2: Container Throughput Performance (2005-2010; Market Share %) Source: Consultants based on data from Informa UK Limited (2012). Furthermore, despite the fact that fierce competition is challenging Jamaica’s container shipping market, there are other major developments which should help increase traffic Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 34

36) volumes significantly going forward. North American consumers continue to demand for imported goods from East Asia and from China in particular. Hence, enlargement of the Panama Canal will lead to the switch of considerable volumes fromthe US ‘mini bridge’ containers (presently moving from West Coast ports by rail) to the all-water route via the Panama Canal. Larger ships likely to be employed on routes between Asia and the US East Coast will see Kingston benefit from its ideally placed location to act as the transhipment hub for the US Gulf, East Coast, and other Latin American ports. Domestically, Jamaica is planning for the development of major logistics services facilities that can add value to inward shipments before being shipped out to final destinations. It is expected that this could lead to considerable growth in container throughput at Kingston Container Terminal. The other key driver of demand is cruise traffic. Presently Jamaica operates in a high volume, low margin sector of the cruise market and also with a high dependence on a relatively limited number of cruise lines. Carnival, Royal Caribbean Lines and MSC Cruises together, account for over 80% of the cruise market. In this aspect, Jamaica willneed to ensure that the island remains as a preferred destination compared to other developing competing tourist locations in the region. 3.3.4 Sophistication of demand The level of sophistication in the demand that is presented to Jamaica becomes important if shipping companies that call at the port for services (includes bunkering) are among the most demanding customers. Demanding customers potentially set high standards for efficiency and productivity to be achieved. Ability to meet the needs of these customers will present strong evidence of Jamaica’s competitiveness. The fact that the world’s third largest container shipping line is using Kingston as its primary hub for the region is a positive development in this regard. CMA CGM has also stated its intention to deploy larger vessels to capitalise on new opportunities that are presented with the enlarged Panama Canal. Apart from CMA CGM, Kingston also hosts MSC which is the world’s second largest container shipping line and an active player in the region. However, the dominant hub for MSC appears to be at Caucedo. Nonetheless, the fact that MSC is choosing to put its largest vessels that ply in the region to make direct calls at both Kingston and Caucedo reveals the inherent competitiveness that Kingston may possess. Another major shipping line that is hubbing at Kingston is ZIM. The ability of Kingston to continue to anchor major container shipping lines will allow maritime service Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 35

37) providers, in particular bunkering providers, the opportunity to improve and deliver worldclass levels of service requirements to cater to the needs of these world-class industry players. 3.3.5 Captive demand The captive demand for bunkering is likely to contract in the near future. This is because shipping companies have the choice to select alternative locations to conduct bunkering and other ship-related activities given the close proximity of port facilities in the Caribbean region. The risk arises from the possibility that transhipment cargo is footloose and could shift should economies of scope from calling at a competitor port becomes attractive enough to do so. Hence, addressing the bunkering issue is but one aspect. Specifically, Jamaica will need to develop other competitive ship and port-related services to cater to the needs of shipping companies and in order to become a premier hub and port-of-call in the region. 3.4 Government policy and interaction This section shall establish the policy aspects that the bunkering sector has to deal with including interaction with public agencies and the role of the government. Policies pursued in major competing bunkering centres are also discussed in order to have a comprehensive view on Jamaica’s positioning. 3.4.1 Relevant government policies that affect the competitiveness and commercial viability of the bunkering sector in Jamaica Policy makers recognise that bunkering forms a critical component of an aggregate of ship-related services that will enhance the attractiveness and competitiveness of developing Jamaica into a premier shipping hub. This is also supported by the country’s Vision 2030 Jamaica National Development Plan and the National Energy Policy 20092030 which are designed to place Jamaica in a position to achieve developed country status and have a modern, efficient, diversified and environmentally sustainable energy sector by 2030. Vision 2030 Jamaica is a 21-year long-term national development plan which seeks to place Jamaica in a position to achieve developed country status by 2030. The Transport Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 36

38) Sector Plan is one of the strategic priority areas of the national development plan. In this plan, the aim is to establish Jamaica as a global transhipment and logistics hub. For this purpose, the plan will involve significant investment in infrastructure in the Port of Kingston as well as developing supporting ancillary services that includes diversification into dry and liquid bulk cargoes and development of duty-free shopping, manufacturing and industrial zones. For example, the Kingston Container Terminal has become the busiest container port in the Caribbean following a US$27 billion expansion which increased the capacity of the terminal to 3.2 million TEUs. There are plans to increase capacity further to 5 million TEUs. The National Energy Policy 2009-2030 aims for Jamaica to have a modern, efficient, diversified and environmentally sustainable energy sector. The plan envisions replacing old and inefficient generating plants and a refinery that produces higher-valued refined petroleum products in order to replace imports and compensate for the potential switch from oil-fired to natural gas power plants. Based on planned capital projects and best practices, the refinery is expected to attain its major performance targets. These include improvements in refinery service factor from 85% to 90% and shutdowns from 5 times to 3 times a year. Capital expenditure is projected at US$19 million, an increase of US$7 million over 2011/12. This will involve major restoration/enhancement work in respect of the dock, major tank repairs, piping and other sustaining capital activities geared towards improved plant reliability, efficiency and improved refinery margin. The refinery’s capacity is expected to grow from 35,000 barrels per day to 50,000 barrels. The National Energy Policy 2009-2030 is fully consistent with Vision 2030 Jamaica. There are also plans to grow the Jamaica Ship Registry (JSR). JSR notes that Jamaica has long been at the hub of Caribbean maritime transportation and the country will be able to take advantage of the expanded Panama Canal in 2015. According to the JSR, Jamaica can provide a cost effective and timely movement of cargo utilising a sea/air movement. Towards this end, Jamaica’s Ministry of Transport, Works and Housing continues to support growing the country’s maritime transport sector. According to the National Transport Policy, the Ministry particularly sets the strategic objectives to facilitate the expansion of shipping and berthing infrastructure, transshipment ports and docking facilities for containers, bulk cargo, passengers and fishing vessels. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 37

39) Furthermore, Jamaica’s Ministry of Industry, Investment and Commerce has also pledged support to the shipping industry through investment and positioning of Jamaica as a major logistics and shipping hub with the global logistics hub project. The Ministry noted that the opening of the Panama Canal is going to shift trade in the world and believes that Jamaica can become the 4th node or pillar in the global supply and logistics chain, along with Singapore, Rotterdam and Dubai. Altogether, these developments will have important implications for the commercial viability and sustainability of the bunkering sector in Jamaica. Potentially, the benefits will be a bigger pool of customers and a larger supply volume for bunkering operations. 3.4.2 Policies pursued in competing bunkering centres 3.4.2.1 Freeport Bahamas The Bahamas Oil Refining Company’s (BORCO) Grand Bahamas facility acts as a marine storage terminal and hub to facilitate the flow of oil and fuel-related products into and out of the US. Of the 22.5 million barrels of storage capacity, 2.6 million barrels of capacity are leased for fuel oil. This translates to about 400,000 tonnes. There are plans to increase capacity further by 2.8 million barrels by third quarter of 2013. This will make it the largest storage terminal facility in the Caribbean. Location as a major oil storage facility will lend credible and strong support to developing Bahamas into a major bunkering centre should policymakers want to do so. 3.4.2.2 Cartagena Colombia Improving security conditions and price competitiveness with reference to Panama and Kingston will likely see Cartagena capturing a larger share of the bunkering market in the region. In particular, growing trade between Brazil and countries in East Asia could see greater shipping traffic between the East Coast of South America passing through the enlarged Panama Canal. This could present a good service opportunity for bunker operators in Cartagena. Nonetheless, calling at Cartagena requires some deviation from the main sailing route from Panama Canal by about 1.5 days or 329 nautical miles. In contrast, ships travelling between East Coast of North America and the Pacific Ocean passes through Jamaica. The advantage of Cartagena lies in capturing shipping traffic going between the East and Northern Coast of South America and the Pacific Ocean. Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 38

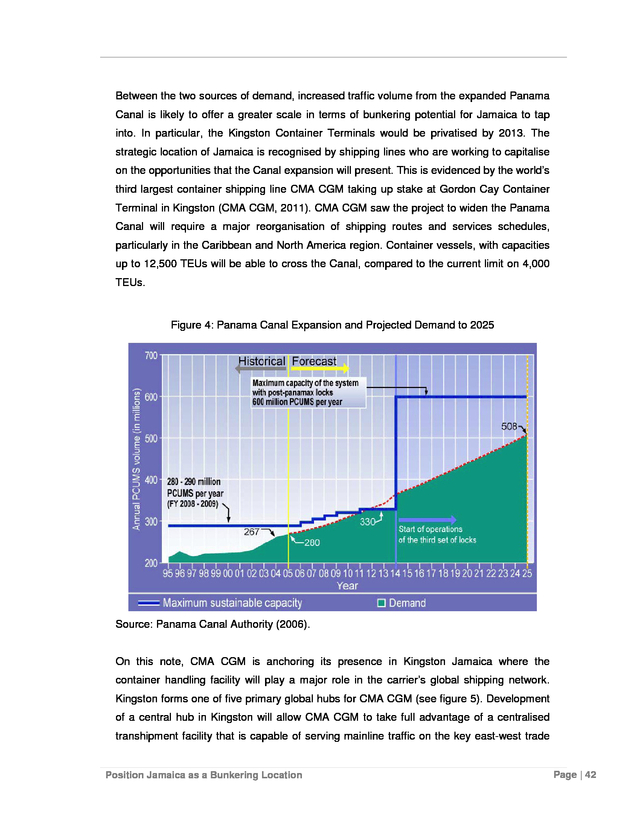

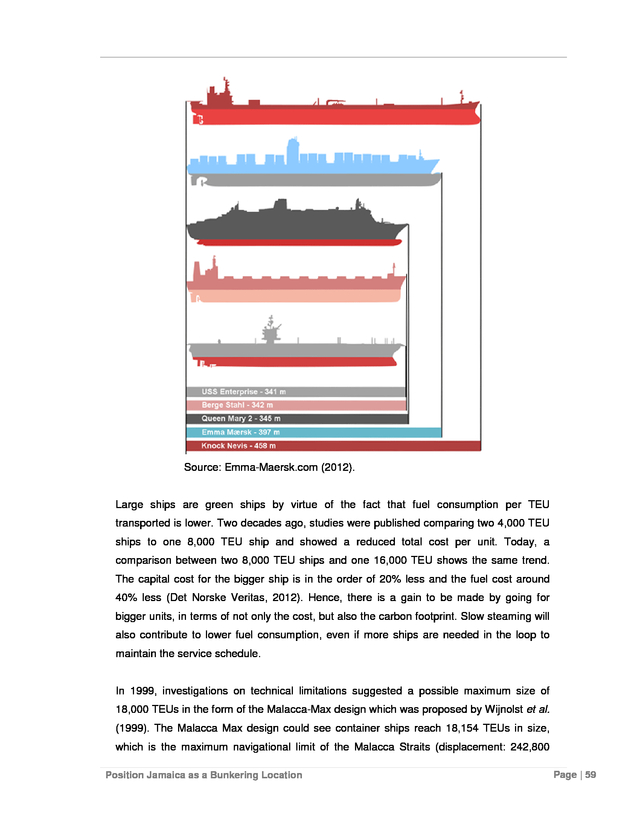

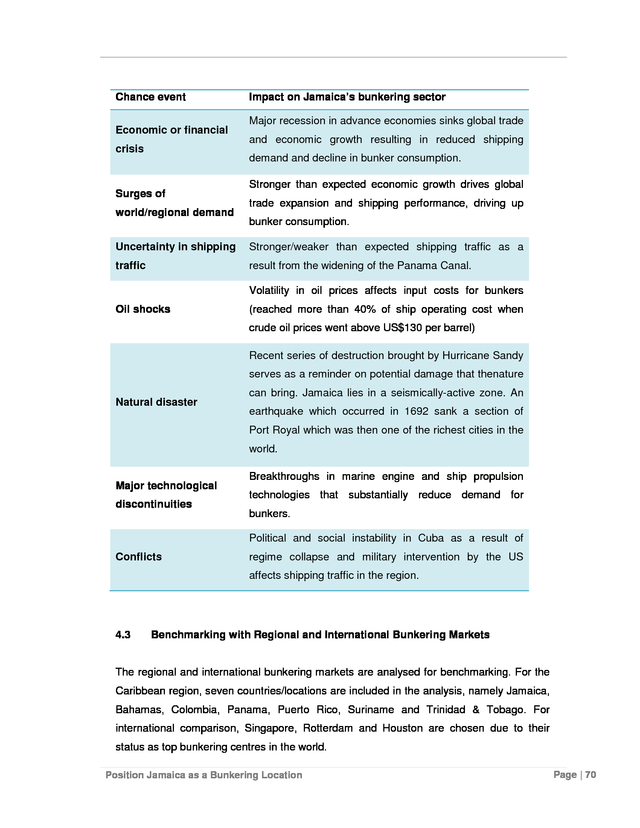

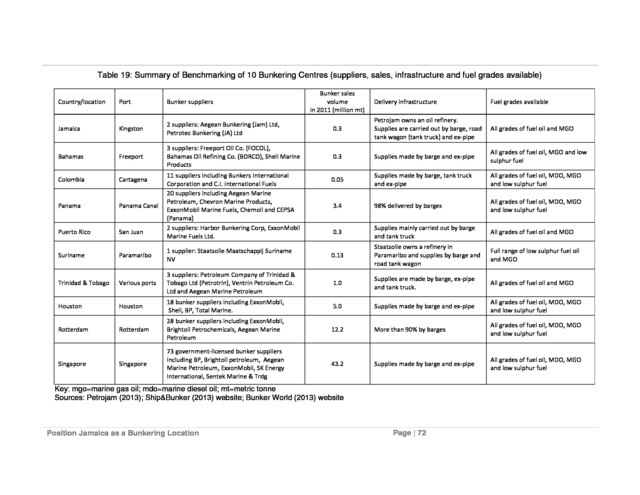

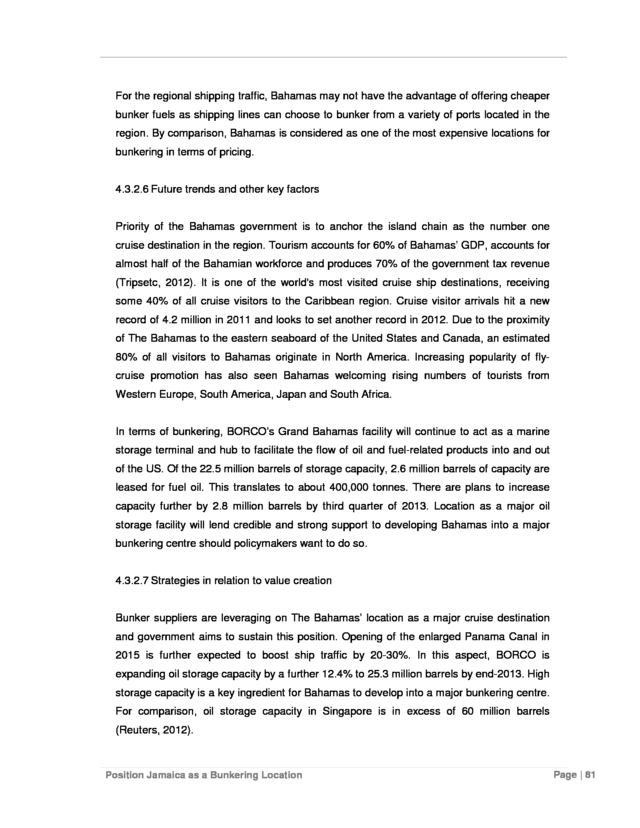

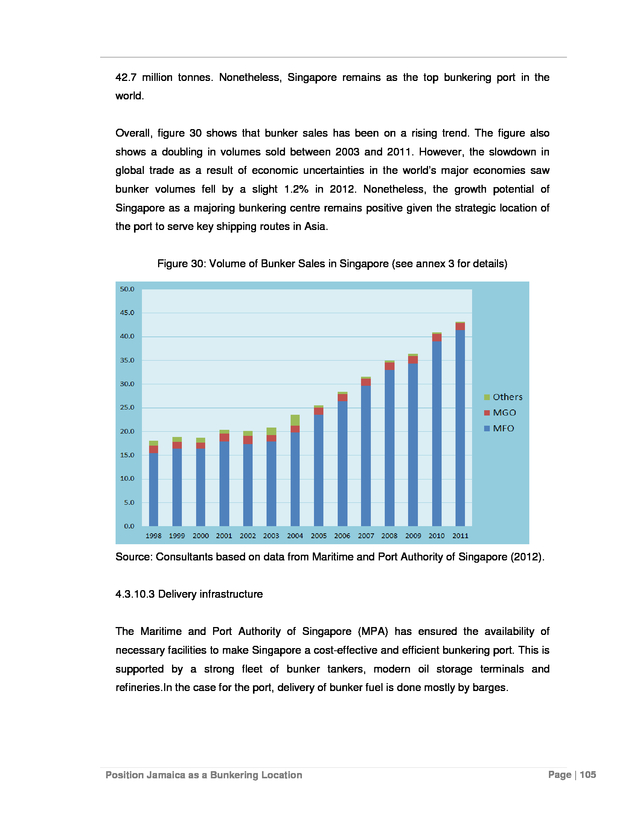

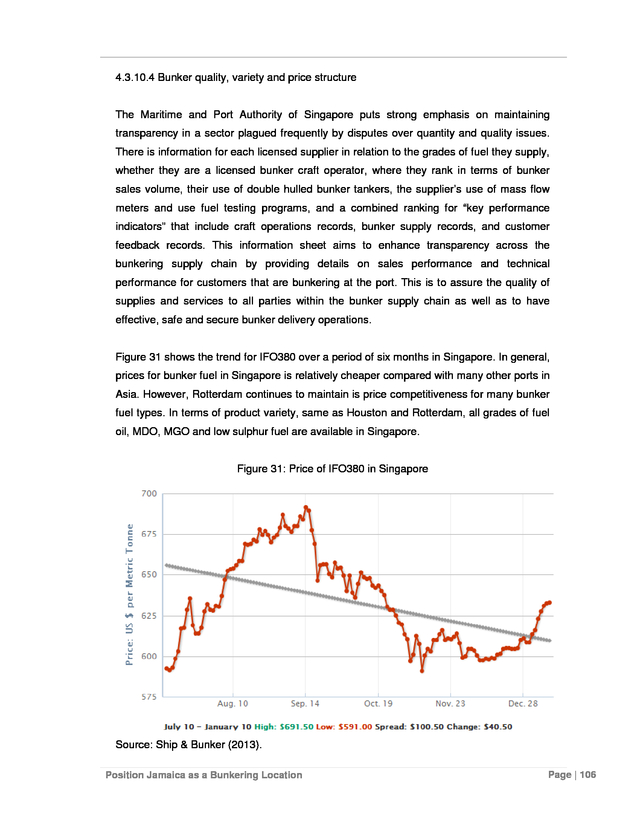

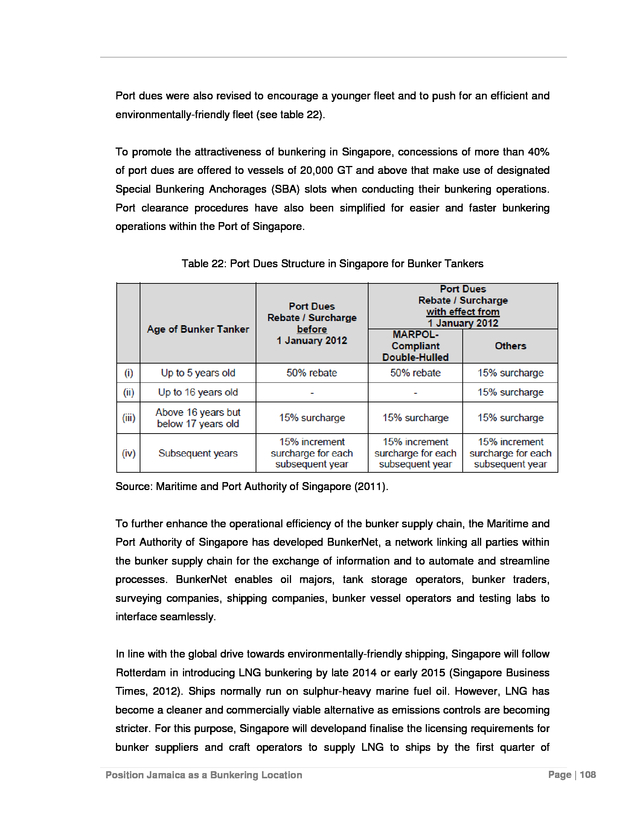

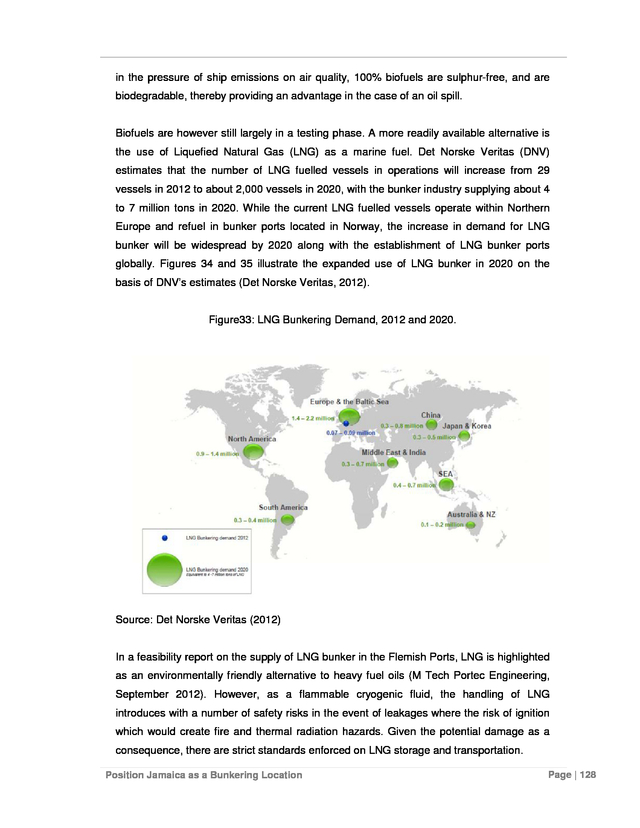

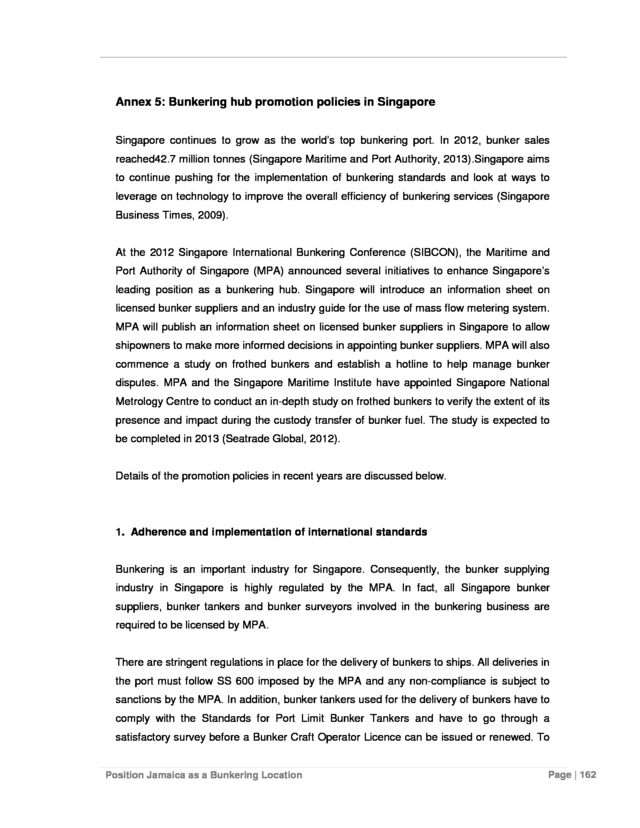

40) 3.4.2.3 Panama Panama is the most proactive competing bunkering centre in the region. To promote the bunkering business, Panama enacted legislation in 1992 to liberalize the petroleum market and to establish Petroleum Free Zones. The legislation created the required incentives to install storage capacity for petroleum and its by-products including bunkers. Therefore, since 1992, Panama has pursued a well-defined policy to promote itself as an international processing, distribution and redistribution centre for petroleum and its by-products. Within the petroleum free zones in Panama, national and foreign companies may perform multiple operations in a special tax regime under high standards and technical specifications. These operations are vast, ranging from imports, storage, refining, and pipeline oil and by-products to bunkering ports, dry docks and other installations. Operating from petroleum free zones means that crude oil and petroleum by-products shall enter and leave these areas without having to pay taxes, provided that sales are destined to the international market. With a petroleum-free-zone regime, large storage capacity and strategic geographical location, Panama aims to develop a fuel distribution and logistics hub like Singapore and Rotterdam in the coming years. In this regard, the Panama government announced plans to make a total investment of US$300 million to install new storage tanks for bunker and other oil derivatives with the aim to double storage capacity from 5 million barrels to 10 million in 2014. Details of bunkering hub promotion policies in Panama can be found in Annex 1. 3.4.2.4 Puerto Rico The Puerto Rican authorities view the tourism industry with particular significance. As such, they are prepared to levy subsidies in the hope of attracting more cruise liners to homeport at Puerto Rico. Nonetheless, given the gradual decline in container shipping traffic, bunker demand could be set on a falling trend. The consultants estimate that bunker lifting from Puerto Rico is on a declining trend. 3.4.2.5 Suriname Position Jamaica as a Bunkering Location Page | 39